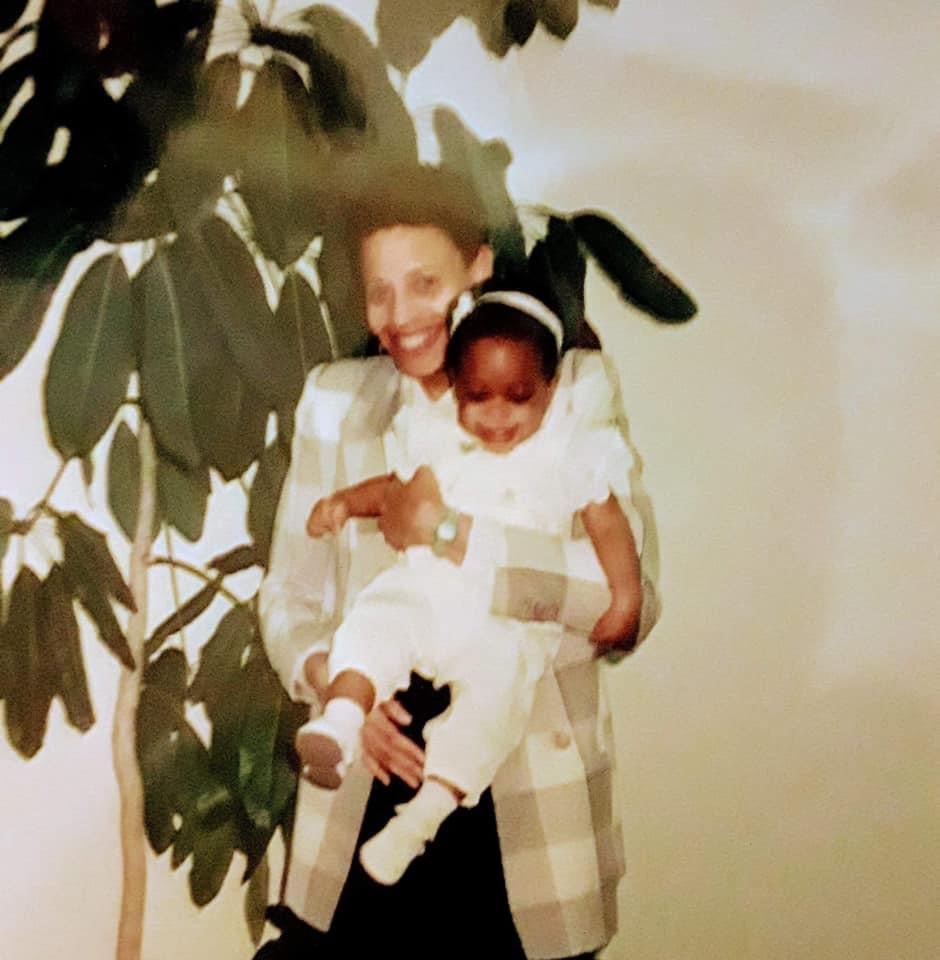

I always love this time of year and getting to spend it with my family to celebrate the holidays. It’s been a tradition for me to travel to Rhode Island to be with my mother, which I’ve been doing since I moved out at age 17. I only missed one year when COVID halted travel. To say I’m a momma’s girl would be an understatement. But being that I’m adopted, moments like this are always more meaningful and important for me to express gratitude for since I was fortunate to be given a forever home.

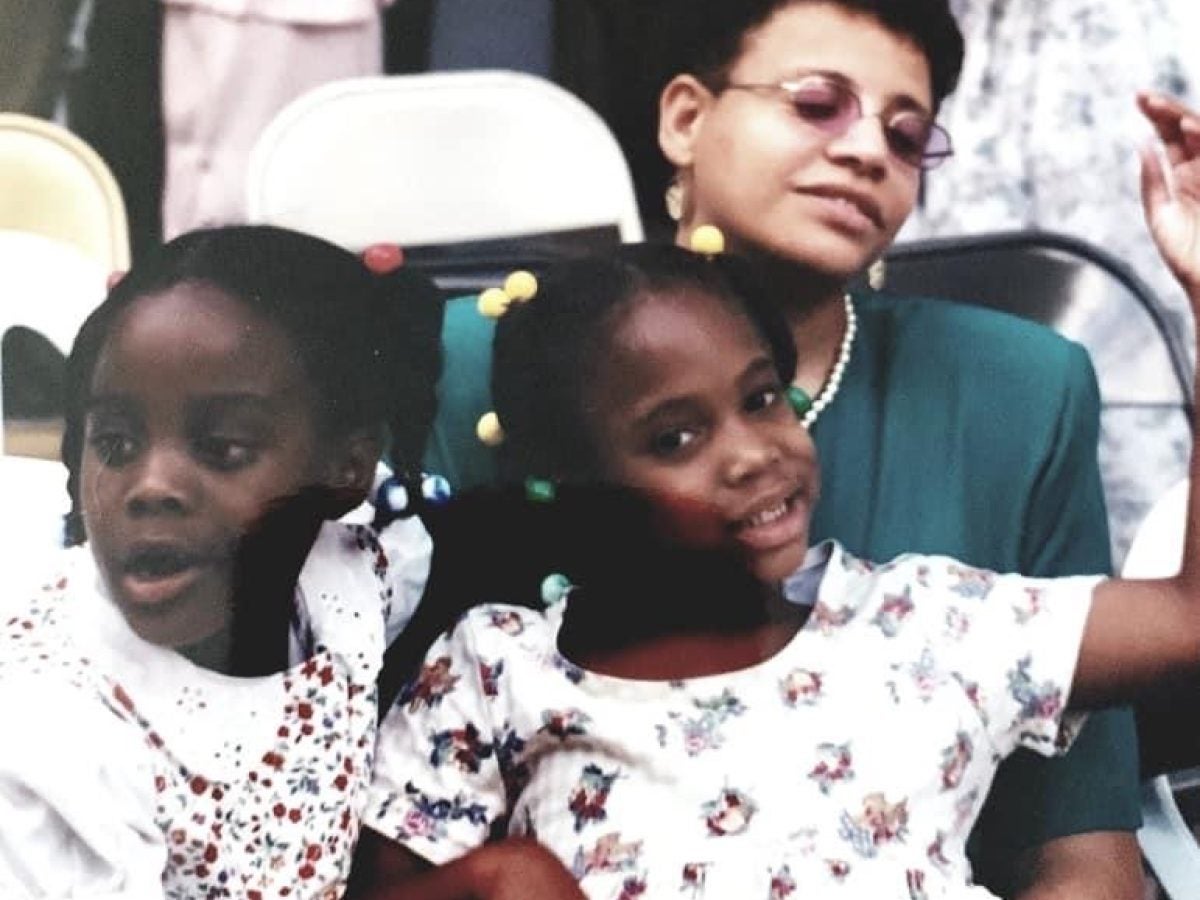

November is National Adoption Awareness Month, and with that in mind, I recently spoke in depth with my mother about how we became a family. October 1991 is when I was welcomed into her home and April 1992 was when I was officially adopted. At only 31 years old and a single Black woman, my mother chose to adopt not only one, but two Black babies out of Baltimore. Because of this, in 1995, my family was awarded the distinction of being the “Family of The Year” by what was then known as the Ocean State Adoption Resource Exchange. As a result, the next year was filled with press tours, being featured on local TV, and attending events at the state house with my mom and sister to share our story.

Granted, adoption wasn’t uncommon, and this was an award that was given out annually. But what made our perspective so special was that you almost never saw or heard about situations where Black adults like my mother were adopting Black children at that time. Nearly three decades later, it’s still something of a rarity to see Black children being adopted and raised by Black parents.

Even when I speak to other people who were adopted, they almost always are surprised to hear that I was rescued by a successful, educated and beautiful Black woman and not a white family. I had the unique privilege of having a Black mother not only love and embrace me, but also help me identify and interact with the world as a Black person. Had I not, I probably would have ended up in a similar situation as most Black children who don’t get adopted—I would have been trapped in the foster care system.

Did you know that as of September 2020, more than 400,000 children were in the foster system in the U.S? And that a disproportionate number of these children are Black and account for only 14 percent of the children in the nation, but 23 percent of the kids in the child welfare system? Let that sink in and know that the problem is only getting worse. What’s scariest about all of this is the disturbing correlation (and increasing trend) between foster care youth outgrowing the system, then eventually flooding prisons—better known as the foster care-to-prison pipeline. What’s even more problematic is this particularly affects youth of color who generally don’t have access to the support and necessary resources to develop personally or professionally. One study showed that more than 90 percent of youth in foster care who have moved five or more times will find themselves in the juvenile justice system.

So why aren’t more Black families adopting Black children?

“The idea of adoption as a natural method of family planning is still not widely embraced within the Black community, contributing to the challenges faced by Black youth and youth of color in finding forever homes,” says Charell Star, a foster care advocate and executive director for Muse by Clio. “Black youth available for adoption through the foster care system right now tend to be older than the age of six while there is a strong preference among hopeful adoptive parents for infants. The older a child is, the less likely they are to be adopted. Discrimination compounds these challenges, as Black children face lower adoption rates even when controlling for age.”

But things are improving according to Jourdan Laws, founder of Noire Adoption, an adoption profile hosting platform centered on Black, biracial and interracial hopeful adoptive parents. “In private adoption there has been a shift from Black babies being placed with whoever will take them to the mothers specifically requesting Black or interracial hopeful parents,” he says. “Once the height of the Black Lives Matter Movement took off during the pandemic there was a major shift.”

She adds, “Most adoption agencies still only have a few Black or interracial couples, if any, so they started reaching out to consultants or my organization, Noire Adoption, that have hopeful adoptive parents to fill that need. My organization was founded specifically to help fill that need, and has the most Black, biracial and interracial hopeful adoptive parents out of every adoption profile hosting platform.”

And adoption is occurring in untraditional ways within the Black community as well. Black families tend to do a lot of kinship adoption, which means adopting within the family. Grandmothers often step in to take care of their child’s kids, as well as aunts and uncles who open up their homes for their nieces and nephews during hard times. Public figures have even done this, from Dwyane Wade being awarded custody of his nephew in 2011, and Marlo Hampton of Real Housewives of Atlanta fame taking in her nephews while their mother battled mental health issues. So while change is taking place, slowly, it is happening and in different ways.

As I spend all the time in the world with my mother during the holiday season, relishing in traditions and being embraced by family, it only makes me more passionate about speaking up to start conversations around Black children deserving loving and permanent homes. And in a time when so many are still in foster care, struggling in unhealthy group home situations, and aging out of the system, it’s incredibly necessary.