This story is featured in the January/February issue of ESSENCE.

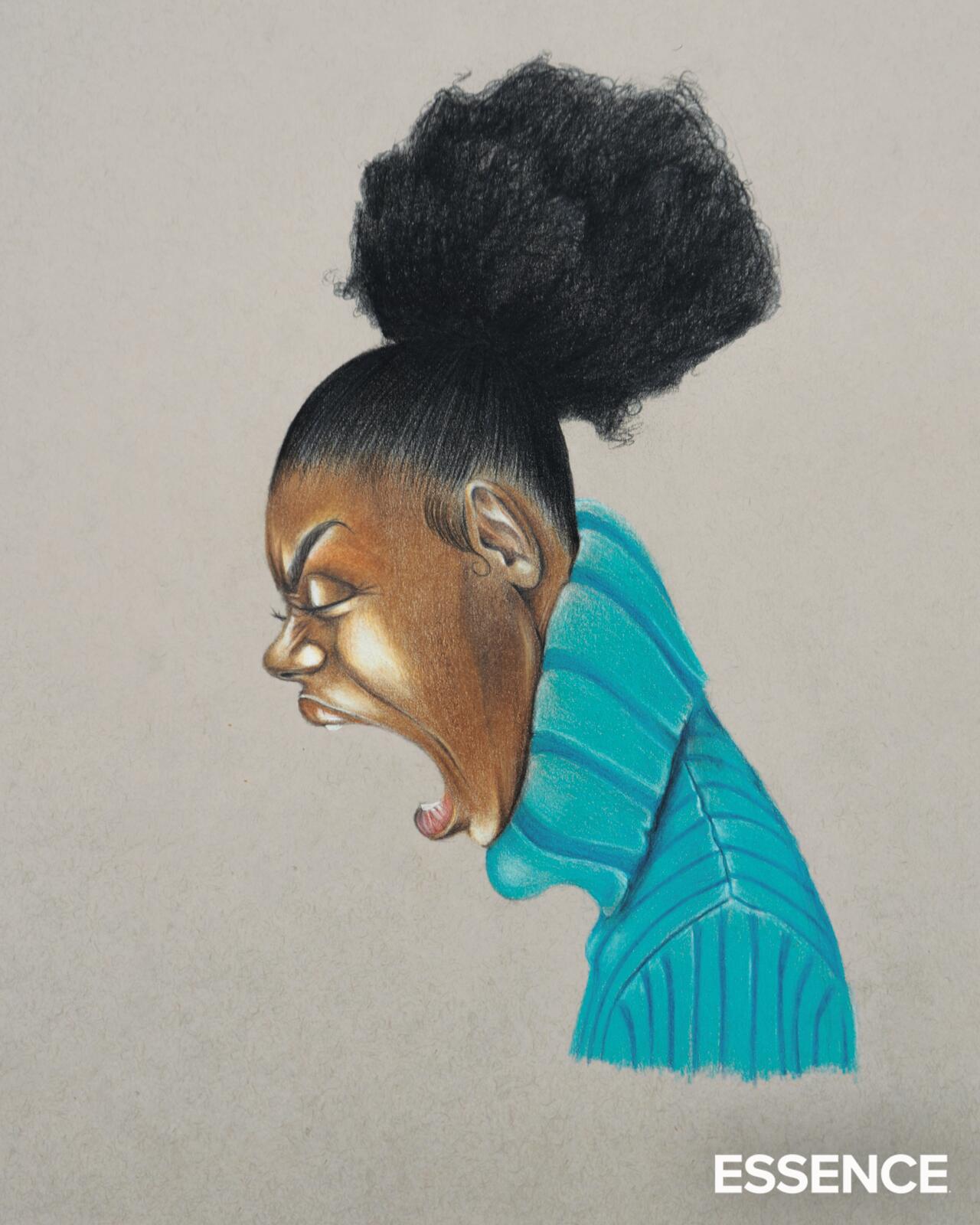

Black women have a fraught relationship with anger. Whether we’re distancing ourselves from the harmful stereotype of the combative, neck-rolling “Sapphire” (birthed from America’s Jim Crow era) or trying to avoid the repercussions of expressing warranted frustration in the workplace, we’re good at “sucking it up” and “pushing through.” But being angry is our birthright, argues licensed psychotherapist Patrice N. Douglas—one that was taken from us during slavery.

“Anger is a natural response to certain provocations,” Douglas says. “But because we were considered property and didn’t have a say in things, we never had the privilege or permission to embrace and express our emotions appropriately. And anger can do so many great things for us as people.”

Even today, our anger, when we do express it, gets filtered through the stereotyped lens of the Angry Black Woman—costing us professionally and personally, and, in the most extreme cases, putting us in life-threatening situations. Aware of these outcomes, many Black women have opted out of exploring their anger and leaned into being “unbothered” instead.

Sesali Bowen, author of Bad Fat Black Girl, says this popular cultural response is a “very cute distraction” rooted in parody: “Avoiding our anger has never existed as a true, authentic solution.” Being “unbothered” gives us a way to walk away from a natural emotion we have no safe way of expressing and haven’t had the opportunity to understand.

“For us, the avoidance came with a little bit of satire— because there is no denying all of the things we have to be mad about,” Bowen adds. “So we say, ‘I’m going to avoid the things that make me angry, because there is no space for my anger.’ In fact, we exist in a culture where anger is harmful to us. That’s part of the reason we run from it—because where does it go? But let’s just say we do lean into it. What does that get us?”

Admitting Your Anger

Before we can manage anger, we must know how to identify it. Noreen Palmer, an anger-management psychotherapist, says that starts with the physiological symptoms. “It’s like lightning hits the brain, and then your emotions start,” she says. “There’s something out there that triggers you. And you can’t catch yourself if you can’t catch that feeling—and you only have a few seconds to do it.” According to Palmer, co-author of Going Off: A Black Woman’s Guide for Dealing With Anger and Stress, the physical symptoms of anger can include tightness in the chest, numbness in the face or trembling in the hands.

After this bodily response, Douglas says, there’s a critical 30-minute window during which internal processing should happen. “Our nervous system is always so activated that for Black women, a big part of anger regulation is to slow down, instead of springing into action,” Douglas explains. “We’re always solution-oriented. We’ve got to figure it out, because life moves on—that’s what’s been conditioned into us.”

For a healthier response, she recommends taking “time-outs”—which might include strategies such as deep breathing or meditation, to slow down our nervous system, or even just taking some time away from others to be in tune with our emotions. “If you’re angry, it helps to eat a snack, go watch some TV, take a break,” she says. “Make sure you’re not sleepy. Make sure you really understand what you’re feeling before you act on it.”

Listening to Your Anger

When Kaija Pack’s husband died, she was pissed. Pissed that he died, and pissed that he left her with six children to care for. In grief counseling, she told her therapist as much. “She looked at me and said, ‘Well, you can’t be pissed off. You have to learn how to deal with it,’” recalls Pack. “That was not what I needed to hear.”

The relationship between grief and anger is common, says Douglas, as anger is often a secondary emotion. “Anger might not be the primary thing that we’re feeling,” she explains, noting that we could also be sad or embarrassed. “We really don’t know what else we’re feeling.”

Seeking a way to deal with her primary emotion, grief, and its companion, anger, Pack opened Break Life, Houston’s first Black-owned therapeutic rage room, for people to embrace and release anger without repercussion. In addition to smash rooms, she also offers painting therapy and spaces for patrons to cry and yell without judgment. Since the space opened, she’s hosted everything from divorce parties to therapy for children in foster homes. “We see a vast array of emotions,” she says. “We see a lot of sadness. We get a lot of breakups—not just [romantic] relationships, but we see a lot of friendships breaking up. And the only way that it’s going to work for us is to understand what emotions we go through and why.”

Anger as a Way Through

Embracing anger is more than just bucking the Angry Black Woman stereotype. Research like Donna S. Davenport’s “The Functions of Anger and Forgiveness: Guidelines for psychotherapy with victims” (1991) and Susan M. Johnson’s “The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy: Creating Connection” (2004) have shown that allowing anger to exist in healthy ways improves the quality of our relationships and is a form of self-care. From anxiety to depression, Douglas says “anger translates to so many health disparities in our community, because we’re not able to use it the right way.” It’s killing us if we don’t properly channel it. Letting our anger exist in a society that equates it to violence is scary—but getting to a place where we welcome the fullness of our humanity, inclusive of anger, is necessary. “Just saying it out loud and meaning what we say—advocating for ourselves, even if we know it may not change things—decreases our low self-esteem,” Douglas notes. “It decreases our depression, because we feel empowered within ourselves, which is one of the biggest components of the Black experience: We always want to feel strong and empowered within ourselves.”

“Yes, there are sometimes consequences, or people don’t want to hear you—but the fact that you’re able to speak about how you feel, that is empowering in itself,” she adds. “Sometimes just expressing our anger is all we need to get past it.”