The Black Health & Wellness Pioneers series for Black History Month is an enlightening and inspirational journey through time that recognizes and celebrates Black individuals’ invaluable contributions to the health and wellness field. Within this series, we delve into the stories and achievements of prominent Black figures who have made significant strides in the realms of medicine, healthcare, fitness, mental health, and holistic wellness.

Although Black women are leading the charge in entrepreneurship and education, making up 13% of the United States, only 5.7% of physicians in the United States identify as Black or African American, according to the latest data from the Association of American Medical Colleges. And when it comes to ophthalmology (a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with diagnosing and treating eye disorders), the percentage of Black ophthalmologists is even lower, at (5.1%). The practice is specific and should not be confused with optometry. Optometrists examine, diagnose, and treat patients’ eyes. Ophthalmologists are eye doctors who perform medical and surgical treatments for eye conditions. Ophthalmologists need to complete 12 to 14 years of training and education, including medical school and are licensed to practice medicine and surgery. An ophthalmologist diagnoses and treats all eye diseases, performs eye surgery, and prescribes and fits eyeglasses and contact lenses to correct vision problems.

Many ophthalmologists are also involved in scientific research on the causes and cures of eye diseases and vision disorders. According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, ophthalmologists can also recognize other health problems that aren’t directly related to the eye and refer those patients to the right medical doctors for treatment.

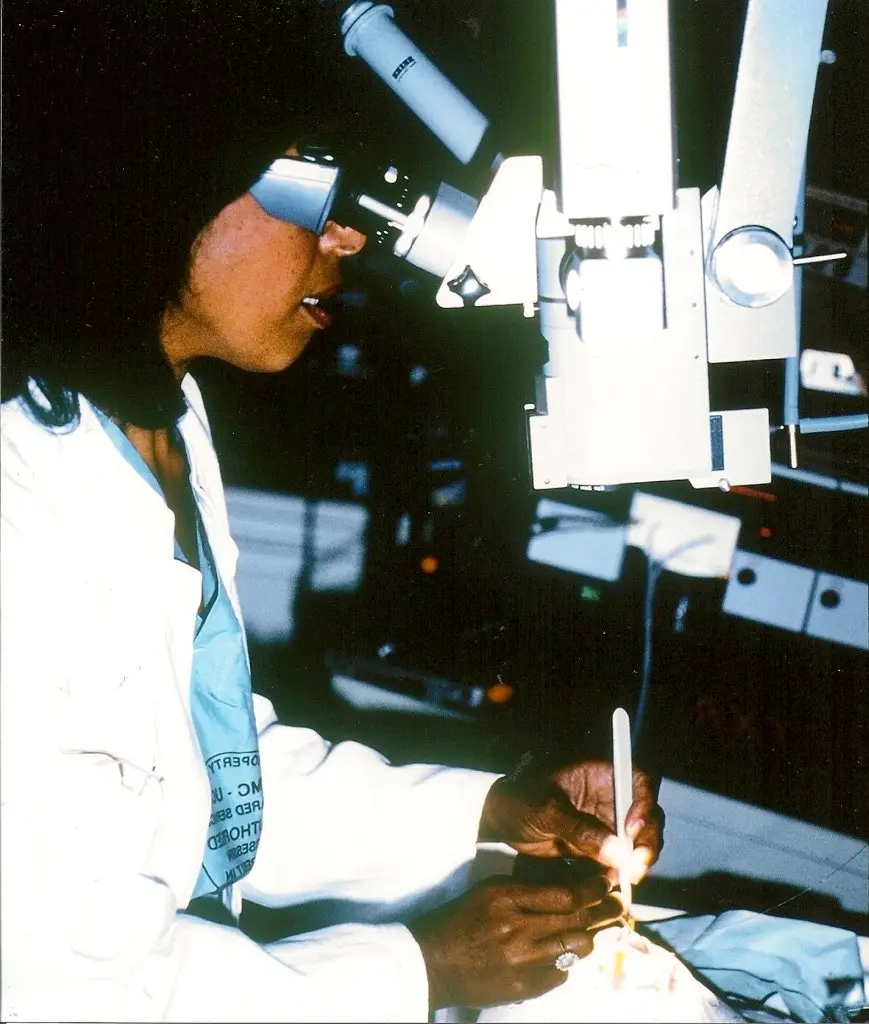

Dr. Patricia Bath was a Black woman ophthalmologist who was a trailblazer for the profession. In 1974, she was the first woman ophthalmologist to be appointed to the faculty of the University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Jules Stein Eye Institute. In 1983, she was the first woman to chair an ophthalmology residency program in the United States, and in 1986 she discovered and invented a new device and technique for cataract surgery known as laserphaco.

Born in 1942, Patricia Bath’s dedication to a life in medicine began in childhood when she first heard about Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s service to lepers in the Congo. After excelling in high school and university studies and earning awards for scientific research as early as age sixteen, Dr. Bath embarked on a career in medicine.

She decided to stuy chemistry and physics at Hunter College in Manhattan, earning a bachelor’s degree there in 1964. She received her medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., interned at Harlem Hospital from 1968 to 1969, and completed a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University from 1969 to 1970.

“Disproportionate numbers of blacks are blinded by preventable causes,” Dr. Bath wrote in a 1979 paper in the Journal of the National Medical Association. “However, thus far, no national strategies exist for reducing the excessive rates of blindness among the black population.”

After her internship, she completed her training at New York University between 1970 and 1973, where she was the first African American resident in ophthalmology. Bath married and had a daughter Eraka, born in 1972. While motherhood became her priority, she also managed to complete a fellowship in corneal transplantation and keratoprosthesis (replacing the human cornea with an artificial one).

A young intern at Harlem Hospital and Columbia University, Bath, was quick to observe that at the eye clinic in Harlem, half the patients were blind or visually impaired. At the eye clinic at Columbia, there were very few obviously blind patients. This observation led her to conduct a retrospective epidemiological study, which documented that blindness among blacks was double that among whites. She reached the conclusion that the high prevalence of blindness among blacks was due to a lack of access to ophthalmic care.

As a solution, she proposed a new discipline, known as community ophthalmology, which is now worldwide. Community ophthalmology combines aspects of public health, community medicine, and clinical ophthalmology to offer primary care to underserved populations. Dr. Bath also spearheaded bringing ophthalmic surgical services to Harlem Hospital’s Eye Clinic, which did not perform eye surgery in 1968. She persuaded her professors at Columbia to operate on blind patients for free, and she volunteered as an assistant surgeon. The first major eye operation at Harlem Hospital was performed in 1970 as a result of her efforts.

In 1974 Bath joined the faculty of UCLA and Charles R. Drew University as an assistant professor of surgery (Drew) and ophthalmology (UCLA). The following year she became the first woman faculty member in the Department of Ophthalmology at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute. When she became the first woman faculty in the department, she was offered an office “in the basement next to the lab animals.” She refused the spot. “I didn’t say it was racist or sexist. I said it was inappropriate and succeeded in getting acceptable office space. I decided I was just going to do my work.” By 1983 she was chair of the ophthalmology residency training program at Drew-UCLA, the first woman in the US to hold such a position.

Despite university policies extolling equality and condemning discrimination, Professor Bath experienced numerous instances of sexism and racism throughout her tenure at both UCLA and Drew. She later took her research abroad to Europe. Her work was accepted on its merits at the Laser Medical Center of Berlin, West Germany, the Rothschild Eye Institute of Paris, France, and the Loughborough Institute of Technology, England.

In 1977, she and several other colleagues founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, an organization whose mission is to protect, preserve, and restore the gift of sight. Dr. Bath was also a laser scientist and inventor. Her interest, experience, and research on cataracts lead to her invention of a new device and method to remove cataracts—the laserphaco probe. When she first conceived of the device in 1981, her idea was more advanced than the technology available at the time. It took her nearly five years to complete the research and testing needed to make it work and apply for a patent. Today the device is used worldwide.

In 1993, Bath retired from UCLA Medical Center and was appointed to the honorary medical staff. After that, she advocated for telemedicine, the use of electronic communication to provide medical services to remote areas where healthcare is limited. She has held positions in telemedicine at Howard University and St. George’s University in Grenada.

However, her greatest passion was fighting blindness until her death in 2019. “The ability to restore sight is the ultimate reward. My love of humanity and passion for helping others inspired me to become a physician,” she once said.