Almost a year ago, I made the big move from my hometown of Austin, Texas, to Brooklyn, New York. Now, I’ve made the East Coast move before, almost 15 years prior, when I went to college in the mountains of Massachusetts at Williams College, but this move was quite different. It wasn’t a move to advance my academic prowess, to pursue a job per se, or to nurture a romantic partnership. It was, in essence, just for me. And after spending most of my adulthood being a visible community voice in Austin, leading conversations of equity and justice as a racial justice practitioner and DEI strategist, it was a hard decision to articulate to family members, friends, and colleagues alike.

When anyone asked me what was prompting the move, I’d prepare a dissertation around “Well, it will be great for expanding our partnerships at Rosa Rebellion,” a production company centered around creative activism I co-founded, or “Most of my clients are on the East Coast.” I hoped either one of those responses would satisfy their curiosity, or perhaps their judgment. It took me a long time, a few therapy appointments, and lots of conversations with God, to finally get comfortable simply saying, “Because I want to.” This move, in truth, was about tending to my whole Black self — heart, mind, and soul. An invitation to discover, deconstruct, and deepen my identity as a Black woman detached from my labor, service, and the white gaze of Texas’s capital city.

Now, if you’ve never been to Austin, you may not understand its unique cultural positioning deep in the heart of Texas. A state known as much for football and barbeque as it is recognized for its oppressive political state and conservative social ideologies, Austin has positioned itself as a creative center and self-proclaimed liberal bastion in the midst. But as a Black girl born and raised in the ‘90s, I know first-hand that Austin hasn’t always lived up to the progressive hype, and certainly has not organically nurtured a space of belonging for those traversing the city’s streets with melanin. This contradiction has been at the center of both my work and my own identity formation for most of my adult life, perhaps unconsciously muting parts of my self-expression and often restraining my Blackness as an act of service rather than a self-defined identity.

So, last spring, as I packed up my life in East Austin, I began the process of designing a new expression of myself, style, and story in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. In designing my apartment, I, in turn, designed a personal practice of joy and liberation. In response to America’s ongoing insistence to have many of us play the role of mammy, mule, or martyr, designing my 4th-floor walk-up has been healing, and dare I say, revolutionary.

Author and modern theologian Cole Arthur Riley says it like this: “To make a home – to construct some small site of resistance where you have agency; where you might breathe a little deeper, where you hold the key – is no minor liberation. The oppressor is not only interested in simply stealing the physical space of a people, but the dignity and sense of self that comes with it.” The very act of claiming, occupying, and constructing any space as a Black woman in this country is an act of defiance, and to do so in the privacy of this home has bequeathed me a renewed sense of agency and autonomy.

Now, an appreciation for aesthetics was not new to me. I’ve been known to serve lewks in my lifetime, and Instagram has been as much of a platform to disrupt the triflingness of American oppression as it has been to journal my weekly fits. Recently, I’ve discovered the power in giving one’s aesthetic a language. Interior architect and founder of Mild Sauce Studio, Shane Charles, has masterfully offered Black millennials language to define and capture our aesthetic choices, interrupting the Euro-centric terminology that often leaves our experience and taste on the margins. According to one of her Instagram reels, the story I’ve chosen to tell in my home is somewhere between “Harlem Deco” and “Afro-Caribbean Baroque,” which seems quite fitting given my Bajan roots and my appreciation for the Harlem Renaissance. Birthed from a sense of revolution, at the intersection of art, literature, music, and style, the Harlem Renaissance re-fashioned Black political and cultural identity. Both these style sensibilities are grounded by color, texture, and a resistance to white colonial presence, and I sought to emulate this same sense of freedom and autonomy.

Starting with the kitchen and dining space, I chose hues of green, pink, and yellow. Playing off the muted sage green painted walls, my first purchase was a pair of vintage Thonet kelly green chairs that I found (and hard-fought haggled for) on Facebook Marketplace. They centered the color story of the room and gave me the confidence to invite color and, thus, expressions of me into the room. Every time I rejected the urge to choose a neutral shade or what I perceived as a more subtle choice, it felt like an exercise in resisting the need to quiet myself to be more palatable or acceptable (reminiscent of my present experience having to re-articulate my work or voice in the wake of anti-DEI sentiment to be more accessible).

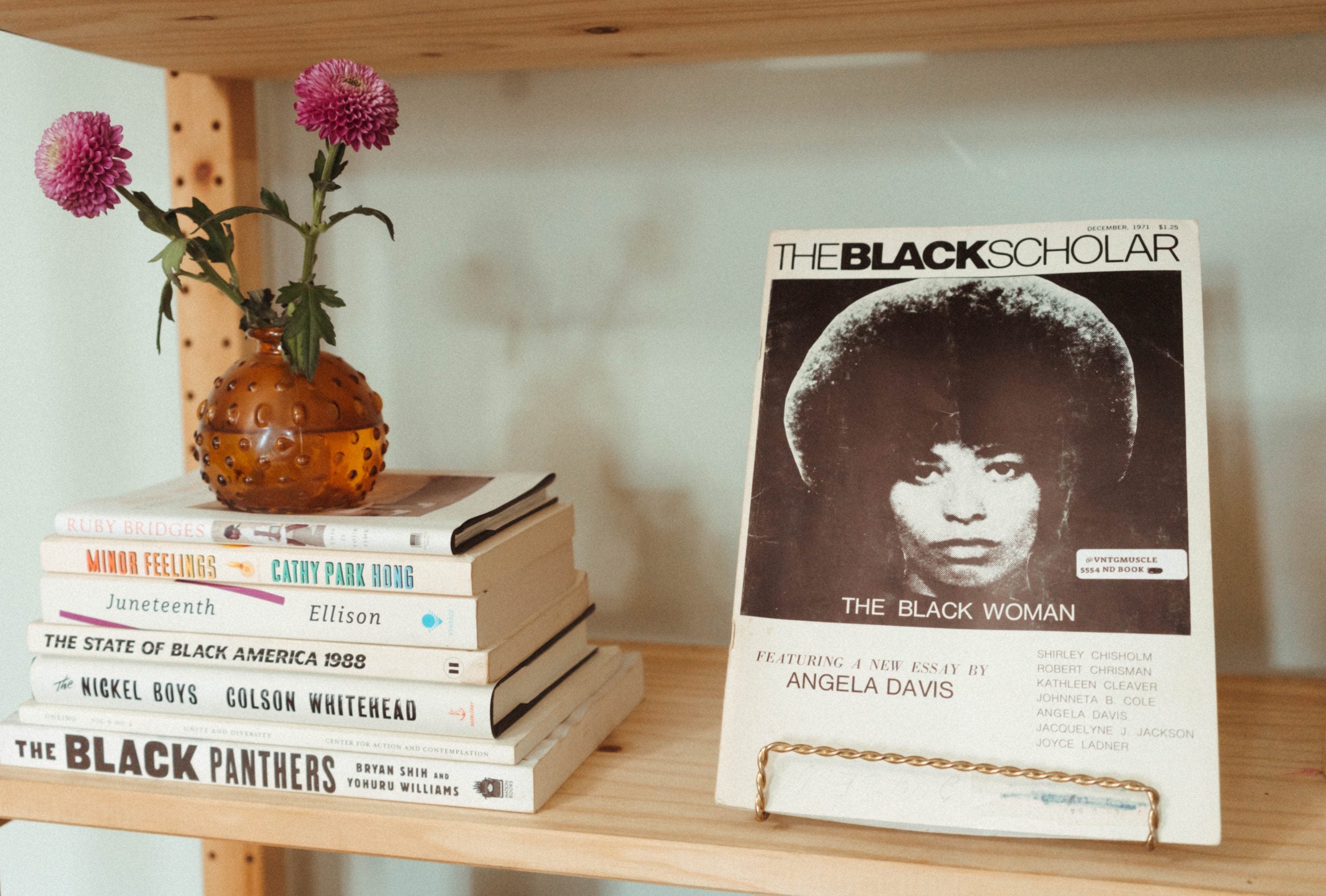

Another invitation to tell a story of Black beauty and brilliance was through the curation of my bookshelf. From the bold prose of Audre Lorde, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison and the author of my favorite childhood book, Aunt Flosie’s Hats (and Crab Cakes Later), a book that re-oriented my world around Black fashion and Black history, to the vintage pieces of history found in the immaculately curated archives of Black Market Vintage, (a 1973 issue of The Black Scholar magazine with Angela Davis on the cover and rare special edition painted plates of Black women dancing and praying, commissioned by the New York-based Heritage Society), assembling these shelves reminded me to take daily stock of all the voices that have helped me fashion my story as a Black woman.

The decision to center color was a choice to disrupt any remnants of placating the status quo and a chance to reclaim my ancestral roots. This was most viscerally expressed in my living room – playing with the color orange, which traditionally represents joy, vitality, imagination, and pride. The focal point of my living room is a large rug with a checkered rust and crème print, spreading over the entirety of the room, making it impossible to ignore or silence its presence. My use of shades of orange and rust were accentuated by vibrant art – the faces of liberated Black women and scenes of Black joy (many pieces I acquired from my paternal grandmother’s extensive collection and others collected through years of shopping at community markets in Austin and Brooklyn).

A few years ago, I was interviewed for an article highlighting some of Austin’s taste-makers and I was asked how I negotiated being so expressive in my clothing choices as someone working in such a serious field (at the time I was serving as director of the Center of Community Engagement and the Social Justice Institute at The University of Texas at Austin). I believe my response at the time is emblematic of my current energy: “My chosen aesthetic is an extension of my ethos – a resistance to the status quo, and a reminder that in the midst of our fight for justice and equity, we can be expressions of joy.” In this next chapter that I am curating in my little corner of Bed-Stuy, I believe Brooklyn has given me renewed permission to stylize my home, my story, and thus my life in a way that honors my full self.

I’m currently working on a new book/curatorial project called Threaded, exploring how women of color, particularly Black women, have offered us a blueprint for stylizing our resistance. In essence, Black women have set a precedent of fashioning our wardrobes, our spaces, and our lived experiences to articulate radical joy, disrupt political oppression, and inspire a more liberated future. As I sit in my living room illuminated by the light peering through my French doors, surrounded by the plants I bought from my neighborhood Black woman-owned plant nursery, I’m overcome with reflections of the journey of the last year that has led me to this consideration in this moment:

Let home be our place of rest.

Let home be a source of reprieve.

Let home be an act of resistance.

Let home be a portal of revelation.

Let home be a safe space for our rage.

Let home deepen our practice of selfhood. Let home tell our story. Let home be an invitation to dream. Let home permit us to imagine. Let home offer us room to resist the horrors of this world. Let home be a doorway to our collective liberation.