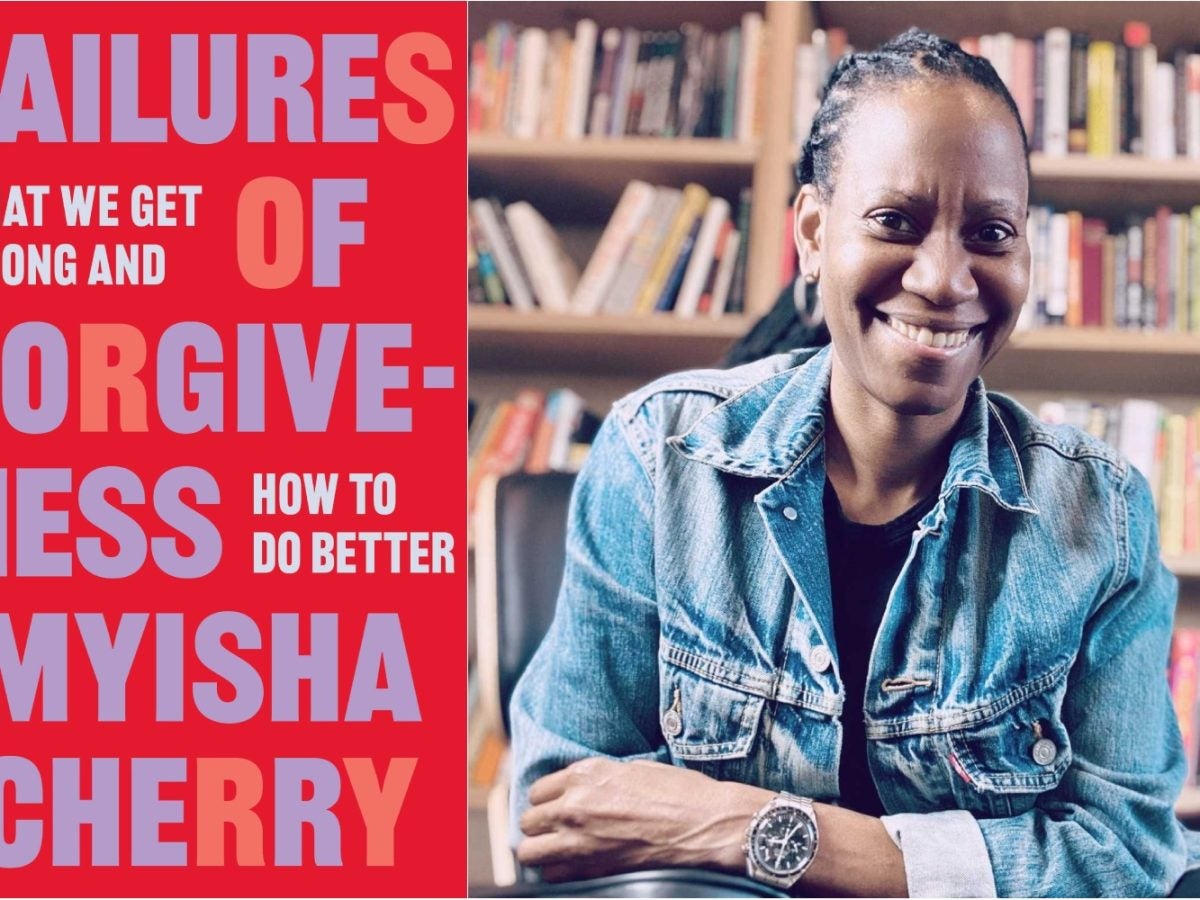

Myisha Cherry demands dignity for wronged individuals in her book Failures of Forgiveness: What We Get Wrong and How to Do Better, placing special attention on Black women. It declares that “commanding people to forgive shows a lack of respect for victims by attempting to bend them to our wills.” For the work, the associate professor of philosophy at the University of California, Riverside and director of the Emotion and Society Lab has examined how society has tried to force forgiveness on injured parties, and as an alternative, she recommends the practice of radical repair.

“Repair is about getting at the root of a particular issue; it’s about engaging in a kind of collaborative action,” she explains to ESSENCE. “It’s about actually investing time and investing resources. It’s not something that’s quick. It’s not something that’s perfect.”

So why are people really interested in forgiveness? She settled on the conclusion that they’re ultimately “thinking about the world being better.” However, we’ve been going about things in the wrong way. “People have a wrong thinking about what kind of repair they ought to be accurately aiming for,” says Cherry. “I think a lot of times we’re willing to pretend that something has been fixed and sometimes that pretending, that hiding things, can make us feel better about conflicts. And the reason that can make us feel better is because we may be afraid to do the kind of real work that’s necessary.”

Loud (and often insincere) apologies reign supreme in our culture. So do hasty acceptances. Failures of Forgiveness cites several examples of this, challenging the public pressure often placed on surviving family members of those slain by racists and police officers to accept the apologies of their loved ones’ killers. “I felt like the way they were going about it was putting all the onus on the victim,” Cherry says.

The questions about whether or not they can forgive come instantly before these people, often Black women, mothers, widows, sisters, can even begin to process their pain. “They want racial reconciliation to happen, but they want the victim to do it,” she says. “It’s incomplete.” She believes true reconciliation comes from actual dialogue. “The right way to go about repair is thinking about it in ways in which we all have a role to play,” she adds. “They were going for repair, but it was in a way that was absolving them.”

She labels this approach an attempt at “superficial repair” or “thrifty repair.” Police brutality is an extreme example, but the need for radical repair applies to microaggressions, infidelity, and other common yet significant misdeeds. Any Black woman on the internet who has been commanded to “educate” someone who has offended them on the spot has felt the pressure to accept an attempt at a thrifty repair-style solution. “Black women bear a lot. We bear a lot for our families. We’re made to bear a lot for the world,” says Cherry. She rejects the idea that Black women should put respectability politics over their well-being. “The strong Black woman stereotype can be empowering, but it also can be disappearing because it seems to give people a lot of permission to mess us over,” she says.

Some of those people include our own family members.

“We’re willing to allow that abusive uncle to keep abusing folks because we’re afraid,” Cherry says. “So, what we try to do is just get the victims to be quiet during those family gatherings.”

Silencing the hurt party can be easier than tackling the issue. “It’s hard to really do work that’s going to restore a relationship. So families settle sometimes,” she adds, but “pretending can only get you so far.”

She continues, “We just want to clean things up very quickly and pack it all away in the name of forgiveness. As human beings, we don’t like bad endings. I think because we’re so invested in the happy ending aspect we’re willing to do whatever we need to do in order to get to that.”

The desire to witness a happy ending can result in unintentional emotional violence.

“We want that so much that we end up treating victims as pawns of our narrative to get to the happy ending, and we can sometimes prioritize the happy ending over the care, and the sensitivity, and the empathy, and the compassion, that ought to be given to them,” she says.

Providing aggrieved parties with patience and support can be the ultimate apology. A party’s unwillingness to provide that can indicate a shallow commitment to reconciliation. If they are not willing to offer more than a “hey stranger” text, that’s not a good sign. Expect more. In fact, Cherry says, require it.

“You have to address the messiness of the relationship in order to continue to go on,” she declares. “If you’re not really willing to deal with the messiness of the human experience and what it is to be in relationships with people, then you can’t actually value relationships with people.”

Failures of Forgiveness: What We Get Wrong and How to Do Better is now available wherever books are sold.