When a loved one passes away, we’re often left grieving the loss—and longing for just one more moment as vivid as the memories we carry of the one who has passed. For some, solace is found in fashion—a classic jacket, a favorite handbag, cherished jewelry that once adorned our loved one’s hands. Items, once worn and carried by departed family members and close friends, can bring comfort and connection to those left behind.

I’ve experienced tremendous loss. My father, Lionel, was killed by a stray bullet in 2013; and in October 2023, my mother, Adrienne, died of glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. An only child, I’m alone in picking up the pieces of what they left behind, trying to go on with a life that has been shattered by unfathomable grief. But I find beauty in the memories, in the pictures of us as a happy family—and in the elegant clothes.

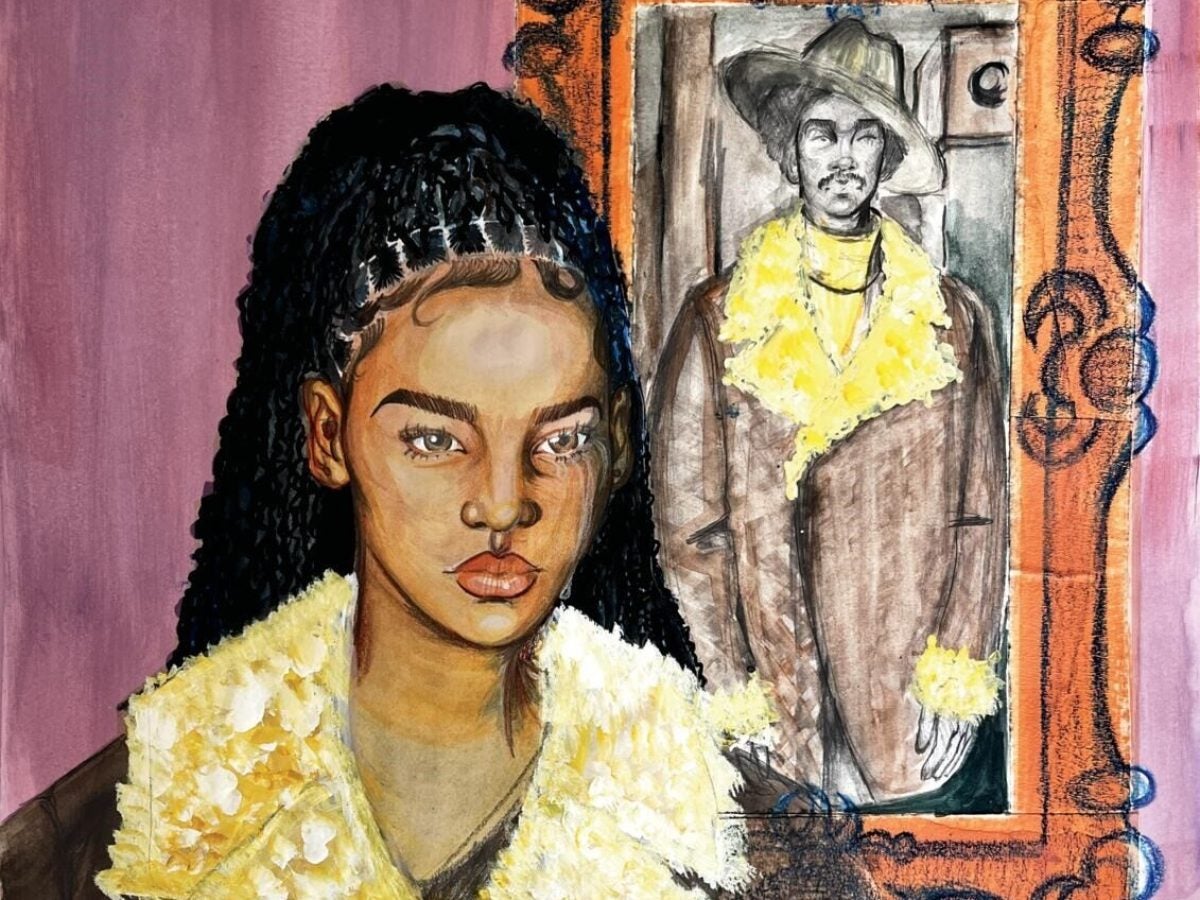

I’ve kept and preserved certain items: the shearling leather bomber coat my father donned to brave Harlem winters in New York City, where he first met my Brooklyn-born mother; her collection of prim and proper hats; the pencil skirts she wore to her accounting job on Wall Street; and the sterling silver snake bangles passed down from those who came before her. I’ve kept these things not only because they are fly and timeless but because I believe my parents’ essence lives on through them. Morgan Murrell has a similar comforting practice. When the journalist lost her twin brother, Matthew, in 2016, she preserved his favorite vest because it made her feel closer to him. “I don’t wear it often, as I’ve tried to retain his smell,” she says. “I just keep it in my closet and look at it.”

The grief hasn’t lessened for Murrell, but safeguarding her sibling’s treasured garment lets her keep some aspect of him alive. “I’m reminded every day that he’s not here and was taken before his time. I think that’s another reason I don’t wear his clothes often—that sadness,” she says. “Still, I want to keep him alive somehow, even if it’s just by having a piece of him through this clothing.”

While she doesn’t want to recommend ways of managing grief to others experiencing bereavement, she does believe that archiving a deceased loved one’s clothes can bring about healing. “If you’re grieving someone you’ve had a special relationship with, I do think you could feel an attachment to their items—because you’d be bringing back memories of when they wore it, or how it made you feel when they were wearing it,” she says. “So I do think it’s special to keep these clothes and hold them close.”

Akua K. Boateng, PhD., a licensed psychotherapist, finds this method of coping popular among her clients who are in mourning. “Sometimes my patients won’t be able to talk about a loss of the person, or the circumstances around the death, but they’ll be able to speak about their loved one’s favorite fashion pieces. It does provide a level of comfort, psychologically and emotionally, to hold on to not only the physical fashion item but the symbolism of it,” Boateng says.

Chase Cassine, a licensed clinical social worker, preserves an entire room full of clothing in honor of his mother, Connie. She passed in 2017 from metastatic breast cancer. Following her death, he decided to leave her room untouched. “I kept her space the same,” he says. “I have placed some of her items in my closet, and I look at them every so often. It gives me the illusion that she’s still here with me.”

Storing fashion items can also help those who didn’t have a close relationship with a departed family member. Fashion stylist Lakyn Carlton admits she didn’t have the bond she wanted with her mother, Begetta, when she was alive. However, after Begetta died in 2019, Carlton started looking for items that reminded her of her mother’s style. “Growing up, I wouldn’t borrow my mom’s shoes or clothes—but once she was gone, things changed,” she says. “I started looking for the clothes she would’ve bought, or for the brands she shopped. It gave me a sense of comfort.”

Clothing is classified as a material item, and often seen as less significant in the totality of one’s life; but in death, these pieces— markers of one’s style and vibrant personality—can have the greatest meaning for an individual navigating a heartbreaking loss.

“When we’re grieving—especially in a situation like mine, where I didn’t have my mother’s items—you yearn for a sense of familiarity, the comfort of having something that reminds you of the person,” Carlton says. “You want to feel like you have a part of them.” In this way, the essence of our loved ones can remain forever near.