Whiskey lovers have come to know and love the taste of Uncle Nearest. With products in more than 45,000 stores, hotels, bars, and restaurants around the globe, the premium whiskey, launched by CEO Fawn Weaver, has become one of the fastest-growing American whiskey brands, reaching a valuation of more than $1 billion earlier this year, according to reports. However, the true story of its namesake inspiration is still unknown to many.

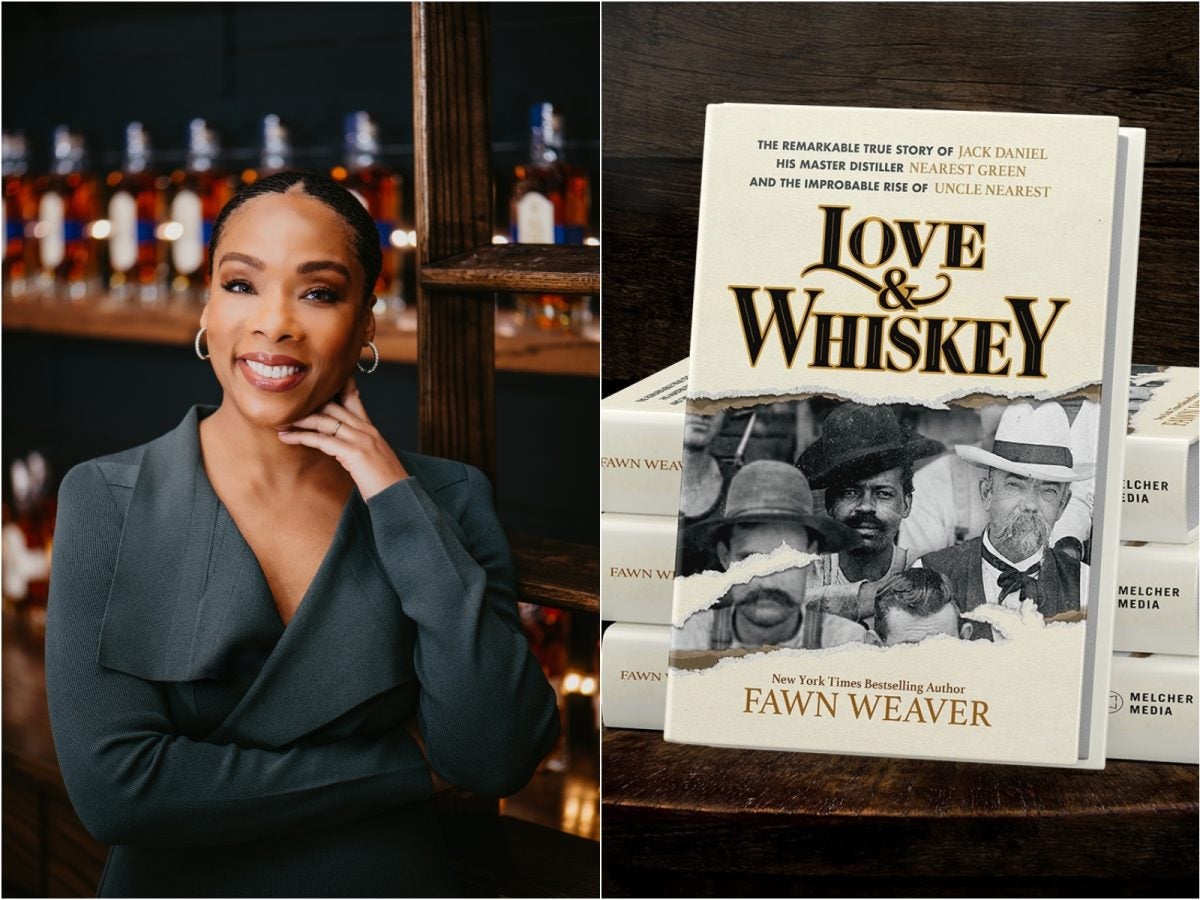

Since the whiskey company’s inception in 2016, Weaver has been the loudest voice, spreading the story of the real Nathan “Nearest” Green, the enslaved man responsible for teaching Jack Daniel how to make the whiskey that would become the famous flavor of Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey. Now Weaver’s taking her efforts to share Green’s history and importance even further with the release of her new book, Love & Whiskey: The Remarkable True Story of Jack Daniel, His Master Distiller Nearest Green, and the Improbable Rise of Uncle Nearest.

Through the accounts of Green and Daniel’s family, friends, and historical records, Weaver details the life and work of Green, who, as a free man, was the first master distiller for the Jack Daniel’s whiskey brand and the first Black master distiller in the world. But more than just a tale of a phenomenal whiskey producer, Weaver’s book shares the story of a dynamic friendship between people of different circumstances during a time of incessant racial turbulence in American history.

“I didn’t expect to find a relationship that involved friendship between a Black person and a white person during that period of time in the South in a town called Lynchburg,” says Weaver. “The stories we learn about the South are very black and white. They miss the nuance. They miss stories like this. So, to me, what was so remarkable about Nearest and Jack’s relationship is that it existed at all.”

It wasn’t just the symbolic relationship between Green and Daniel that shocked Weaver throughout her research, but rather Lynchburg itself and its unified approach as a town. Conversations and historical references to Lynchburg made it clear that the kindness and neighborly compassion granted to every person in the area, regardless of skin color, exceeded the expectations insinuated by its name.

“What gives me so much hope is that this little town above Alabama, which was like a hotbed of hotness and a few hours away from Pulaski where the KKK rose up, Black people and white people were able to create an environment that did not fall in line with Jim Crow laws. It didn’t align with the norm at all,” says Weaver. “Well, that means that in 2024, we should be able to do that in this whole country.”

Weaver credits Green and Daniel’s living descendants—the oldest being 106 and 102 years old, respectively, when she interviewed them—for helping her piece together the story of the whiskey makers’ relationship. It was their memories, Weaver says, that helped her realize how diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives were at the core of Daniel’s whiskey brand long before such phrases as DEI were ever coined. For instance, Weaver explains that early in the Jack Daniel’s brand history, 50% of the workers were Black in a town with a significantly smaller population of Black residents. “That means that Jack and his nephew had to be pulling in Black people from other towns to work there,” she says, adding that Jack Daniel’s staff were also paid on tenure.

“Each person I spoke to who worked there a very long time said that if they were in a job and a white person came into the same job, they were paid more than the white person because [payment] was based on tenure. So, this notion that this was happening in the early 20th century is like a case study on DEI. That was so extraordinary to me,” says Weaver.

During their lifetimes, Daniel spoke highly and often of Green’s influence on the whiskey brand. Daniel’s family also credited Green for the recipe behind the whiskey’s popularity. However, over the years, and following Brown-Forman Corporation’s acquisition of the Jack Daniel’s Distillery in the 1950s, the stories of Green’s role in the brand’s history disappeared from distillery tours. Green’s work and contribution to the rise of Jack Daniel’s whiskey was essentially lost. Jack Daniel’s has since restored Green’s legacy at the distillery in recent years, thanks to Weaver’s research and work with Uncle Nearest Inc.

The nature of Green’s work and relationship with Daniel, as described in Weaver’s book, is more than just a testament to what can be achieved when issues of racial differences are disregarded, though. It’s a lesson of allyship and the success it can bring to generations of people. If anything, that’s what Weaver hopes readers will take away from the story of Green and Daniel.

“Seeing how allyship can be done in a way that is so unapologetic is one of the things that, overall, from the story of Nearest and Jack, is so important for people of every race to get from this,” says Weaver. “If you are a person of power, you have the ability to be an ally and look how different life could be. The only reason this story is coming out is because Jack was an ally to Nearest.”