When my husband, Savali Savali III, died in my arms 16 months ago, the sun turned cold in the desolate world that remained. Perhaps, that’s why this COVID-19 landscape feels so familiar. My heart refused to accept that his collapsed lungs were at war with the cancer cells attacking everything from his bone marrow to his brain. He couldn’t breathe. My body flinches at the remembrance of nights bloated with loneliness and terror, anticipatory grief making my heart jackhammer against my chest.

I always knew that my life would never and could never make sense without him. How could it? Perhaps, then, this novel coronavirus is how I will die. That’s what my anxiety tells me.

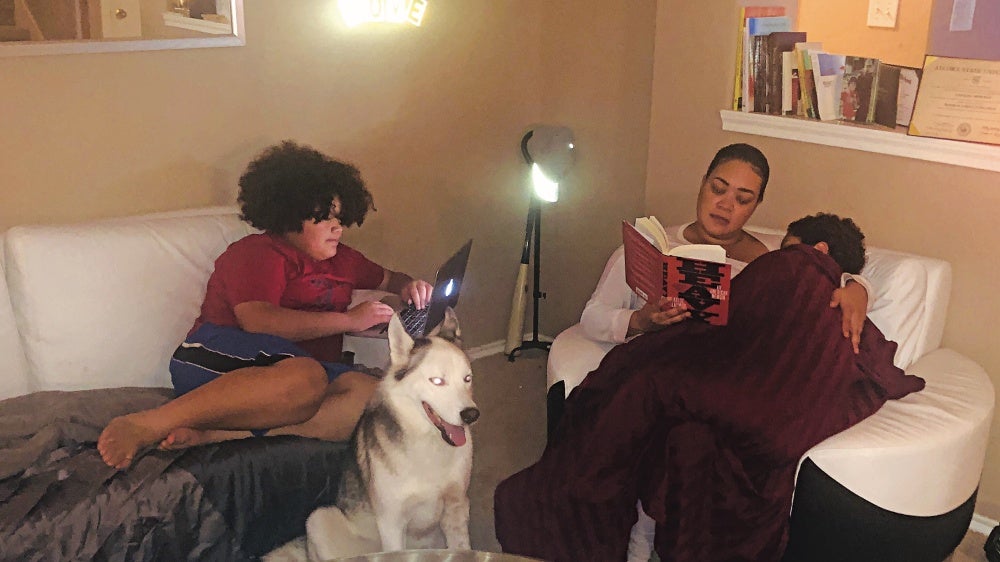

I’m not isolated in any strict sense of the word. Our three sons, two dogs, and my memories keep me company.

Still, as the days yawn, trying not to think about Savali not being here to hold me and calm me down, to help me protect our children, becomes an exercise in futility—and the fullness of those truths make my hands shake. In this home we were building together, raising these boys we love with every ounce of ourselves, his absence is so big and loud and painful that grief has nowhere to hide. One week into physical distancing, I found myself just gazing at his picture.

…raising these boys we love with every ounce of ourselves, his absence is so big and loud…

Kirsten West Savali

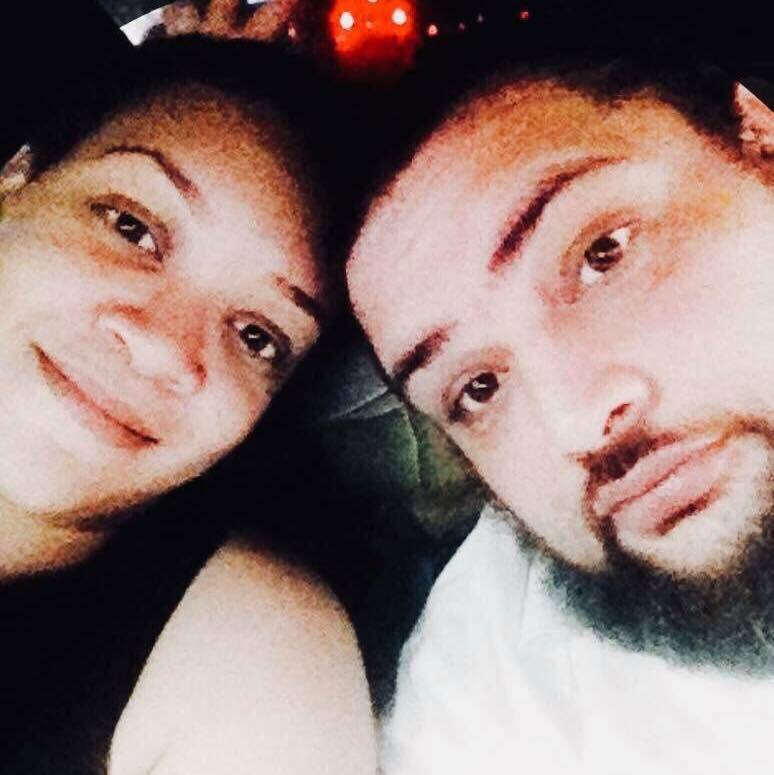

My husband. My love. I remember all of him—the beautiful boy I fell in love with over 20 years ago on an HBCU campus in Atlanta and the beautiful man who sat on the edge of our bed bathed in shadows and anguish, exhausted but never defeated. He wasn’t ready to die. Even now, I still sleep on my side of that bed, instinctively leaving room for him to come home.

As too many people experience unspeakable loss during this global pandemic, the world seems to be frozen in a silent scream. I know it well, but I also know this: last year, the thought of my death didn’t terrify me; I longed for it, only fighting the darkness for our sons. Yet, here I am, shaping a new woman from the pieces time returned to me.

Survival can be ugly. For some people, it looks like hunger and houselessness, binge eating and nausea. There are times it smells like unbrushed teeth and unwashed clothes, when it neglects to nourish us like breast milk thin from stress and too much alcohol. It comes cloaked in terror—the trembling, wailing, and failing often hidden as we struggle, every day, to choose life. It is a brutal beginning and ending. Any glimpse of beauty is both past and future.

I miss Savali with every breath I’m privileged to take in this moment when fathers and mothers, grandparents and children, essential workers and lovers, are exhaling their last.

He wasn’t ready to die. Even now, I still sleep on my side of our bed…

Kirsten West Savali

This fear, rage, and grief I feel—not just for me and our precious boys, but for incarcerated people from Cook County to Rikers Island to Angola to Parchman; for Black people from rural Mississippi to El Barrio—reminds me that I want to survive now.

And standing here, scarred, scared, 16 months after my heart stopped beating, tells me that we will—if, as Audre Lorde teaches us, we consciously study how to be tender with each other until it becomes a habit and work toward dismantling the systems that do us harm.

Our survival will be ugly. It will be beautiful. It will be painful.

It will be so.