There was a beautiful moment right after a baby was born into my hands. I would look in their eyes and wish them a life full of blessings and health. It was my favorite part of my job as an Ob-Gyn–it always felt like such a gift to be in that room.

Childbirth is a powerful, joyful moment. It is the culmination of months of waiting and, for some, years of trying to become a parent. For too many Black and indigenous people, pregnancy and childbirth are also the culmination of a lifetime in a society, and a health system, that does not value them or center their health and well-being. That takes tolls on our bodies, minds and spirits. This lifelong devaluation requires us to be resilient, prayerful and strong, while at the same time weathering our bodies and harming our mental health.

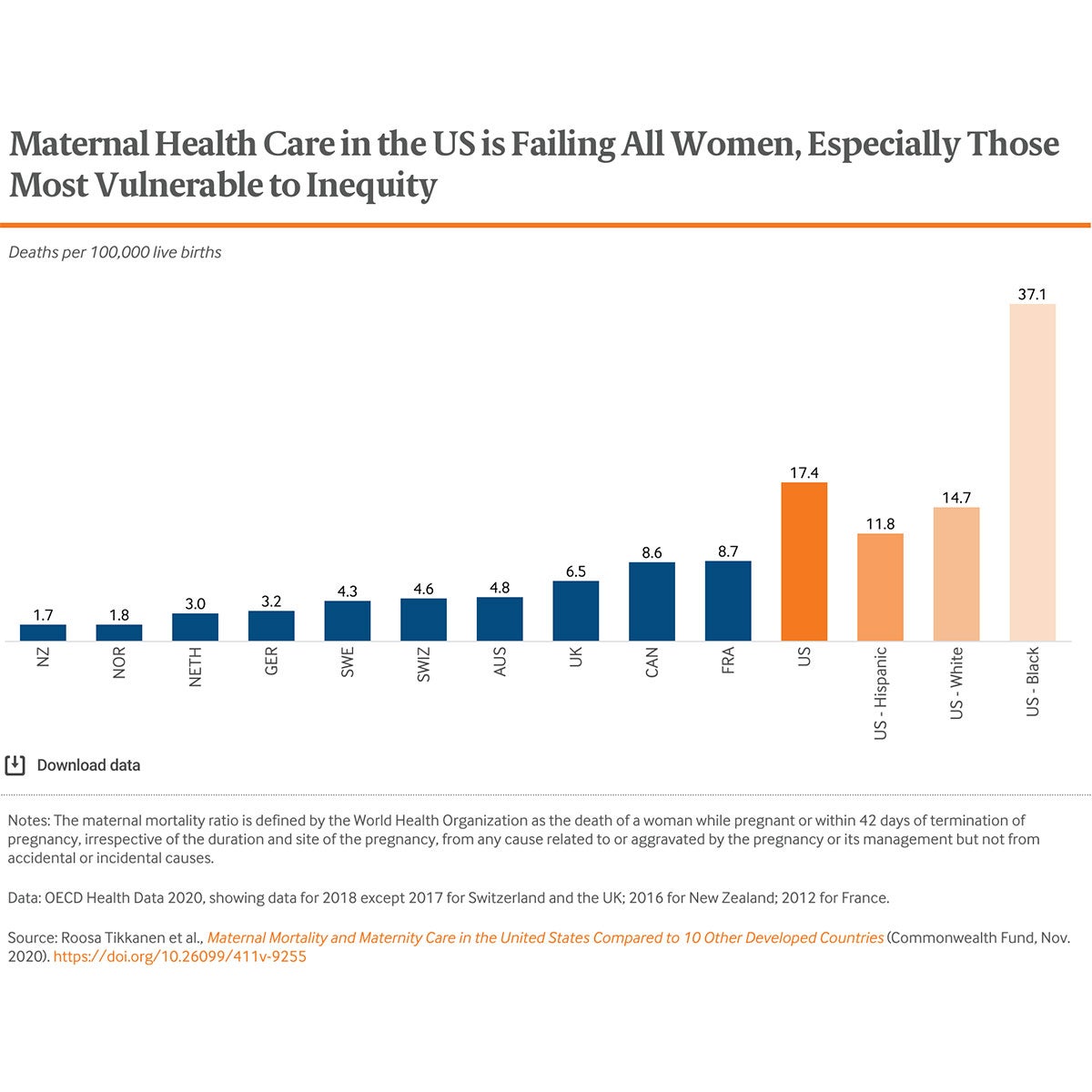

Black and indigenous people in the United States are more than twice as likely to die from pregnancy or childbirth as white people. In fact, American Black women have the highest maternal mortality rate among wealthy nations. We are also more likely to suffer serious complications or illness (maternal morbidity) as a result of pregnancy and childbirth.

I think it is essential to say, especially during this week when we are honoring Black pregnant and birthing people, that the maternal health crisis in the U.S. is a result of generations of deeply entrenched racism, gender inequities and systematic devaluing of Black lives.

For too long, Black people have been blamed for the health disparities and poor health outcomes that systemic racism has wrought on our communities and our bodies. It is time to put the onus on the system itself and the policies that govern much of it.

Our health care system is in no way immune from this country’s history of systemic racism. We can look at centuries of examples of mistreatment—from Tuskegee, to non-consented medical experimentation without anesthesia. However, we don’t need history to tell us what so many of us have experienced firsthand when we’ve gone to a health care provider or the hospital. We know, and data show, that there are assumptions that will be made based on the color of our skin — that we can tolerate more pain, or that we aren’t being truthful. That we won’t be looked at as whole, valuable people. That certain treatment will not be offered to us, and that certain hospitals and clinics in our communities are not up to par.

And beyond all of that, generations of leaving Black communities behind when it comes to economic investment, jobs, transportation, and under investing in the hospitals and providers that serve Black communities have had lasting negative impacts on maternal health care. Numerous studies have described the unequal treatment of Black women when they arrive at health systems where their calls for help are often ignored or deprioritized. It should be no surprise that this consistent devaluing of Black lives has resulted in poorer outcomes for Black pregnant and birthing people.

Even in the face of all of this, we are in a moment that gives me incredible hope. Black women from around the country are taking matters into our own hands in powerful and effective ways. There are coalitions of people of color recognizing the need to address these inequities. We are calling for change in the medical community, change in health systems large and small, and change to the state and federal policies that continue to perpetuate health inequities.

This crisis is not one that Black people created but it is one that we are stepping up to solve. We are stepping up not only because it is a matter of survival- and because it is the just thing to do for Black people- but because it is the right thing to do for our society. A system than protects the most “unvalued” of us- benefits all of us.

Here are just a few incredible examples of the birth equity work happening right now:

- Dr. Joia-Creer Perry’s National Birth Equity Collaborative is working at the national and community level to optimize Black maternal and infant health.

- Representative Lauren Underwood and the Black Maternal Health Caucus have introduced the Momnibus Bill, a comprehensive piece of legislation that would enact a number of policies that evidence shows would greatly improve access to good maternal health care for Black pregnant and birthing people.

- Dr. Andrea Jackson, Melinda Fowler and others at UCSF EMBRACE have developed a promising new model of perinatal care for Black families https://womenshealth.ucsf.edu/coe/embrace-perinatal-care-black-families.

It is so inspiring to see the good that comes from Black women coming together to confront these health injustices and call for a health system that has long ignored us to center us. It is, of course, also exhausting in many ways. We didn’t create this crisis, but we are the most harmed by it, and for that reason we must remain active and vigilant.

Vigilance takes a toll. Seeing people who look like you be harmed, the realization that even in what should be your moment of greatest joy, you cannot outrun the fear that racism will cause you harm. And, while it should not be your responsibility to protect yourself in a system that is designed to care for you, it is important to know how to do just that.

Choosing the right provider is important. When I had my own children, I took great care to select a provider that I knew would see me a whole person and engage me as a partner in my care. In addition, finding and adding a doula as part of your support team has been shown to help improve birth outcomes—the National Black Doulas Association has a resource to help with this. A peer support group of others going through the same journey can also be very uplifting and help alleviate the sense of loneliness that can come with new parenthood.

While asking questions during the pregnancy and birthing process can sometimes feel overwhelming or uncomfortable, it is an important part of the process. The Black Coalition for Safe Motherhood developed by and co-founded with Dr. Leslie Farrington provides birthing people with guidance on how to ACTT for Safe Motherhood– Ask questions, Claim your Space, Trust your Body and Tell your story. It is an excellent resource to help pregnant and birthing people advocate for their needs.

Last but not least, remember that you will also need support during the postpartum period. Many new parents feel a lot of anxiety and pressure during this time because they assume they should know what to do after birth – but that is not the case. Having the support of family, friends and your health care team is important for your physical and emotional well-being. You are strong and resilient, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t need help and support.

In addition to caring for yourself as best you can- mentally, physically and spiritually- you can also play a role in this revitalized Black maternal health experience we are creating from within our community. We need strong support for Black-led efforts to combat this crisis. I hope you will stay engaged beyond Black Maternal Health Week – there is exciting momentum at the community level and at the federal and state level that can drive the change we need to see.

There is so much joy in being a Black woman. From my days in pigtails and too-big glasses sneaking looks at this magazine in line at the grocery story because my mom thought I was too young to read it, to the moment in high school when a provider came to speak and inspired me to follow this path, I have felt grateful for the sisterhood of Black women. I cannot think of a better way to celebrate Black Maternal Health Week than to remember that together we have the power to change the systems and structures that are putting us and our babies and ultimately everyone at risk- and reclaim the unreserved joy we should all be able to feel when we give birth, and always.

Laurie Zephyrin, M.D., M.P.H., M.B.A., is vice president for Advancing Health Equity at the Commonwealth Fund. Dr. Zephyrin has extensive experience leading the vision, design, and delivery of innovative health care models across national health systems.