Reporting live from her apartment bedroom in New York City, Tamela Gordon took to social media to share something she hadn’t done in a very long time. Gordon indulged in a single ear of corn on the cob. Without knowing her backstory, the act might have appeared insignificant. But for Gordon, getting to consume this warm-weather staple was an integral step in her healing and wellness journey.

“After years of dental issues and no insurance, in 2019, I was diagnosed with severe periodontal disease that required full extractions that were replaced with prosthetic teeth,” she says. “The process spanned the course of nearly a year, in which I had to relearn how to speak and chew.”

In addition to struggles with dental health, Gordon’s effort to protect her mental health also proved to be complicated. For 20 years, she worked in the food services industry. During this time, as a way to decompress from a hectic professional environment, she developed a deep passion for what she initially thought was self-care.

“I wasn’t truly healthy—and I got caught up in the fast lane for a little while,” she says. “The self-care that I thought was useful, like getting my nails done and weekly massages, was really counterproductive as a fat, Black woman.”

In order to refine her own individualized plan, Gordon had to explore what self-care looked like for the Black community at large. And in doing so, she realized that she needed to divest from some of the very ideas that the wellness industry often perpetuates.

A 1.5 trillion dollar industry, wellness culture has been known to promote harmful diets that can lead to disordered eating, creating low self-esteem amongst those who solely link wellness to attributes of vanity. The wellness industry also thrives on making optimal health seem attainable for anyone.

“If it’s something that you need, just do it. And if you can’t do it, you’re simply not trying hard enough,” Gordon says is the message she received. She further discovered a heightened sense of shame within wellness communities that individuals carry for not being able to afford proper care for themselves and their families.

“My own dental health and mental health…well, I could not do these things on my own. I did not have the money or the resources,” she says.

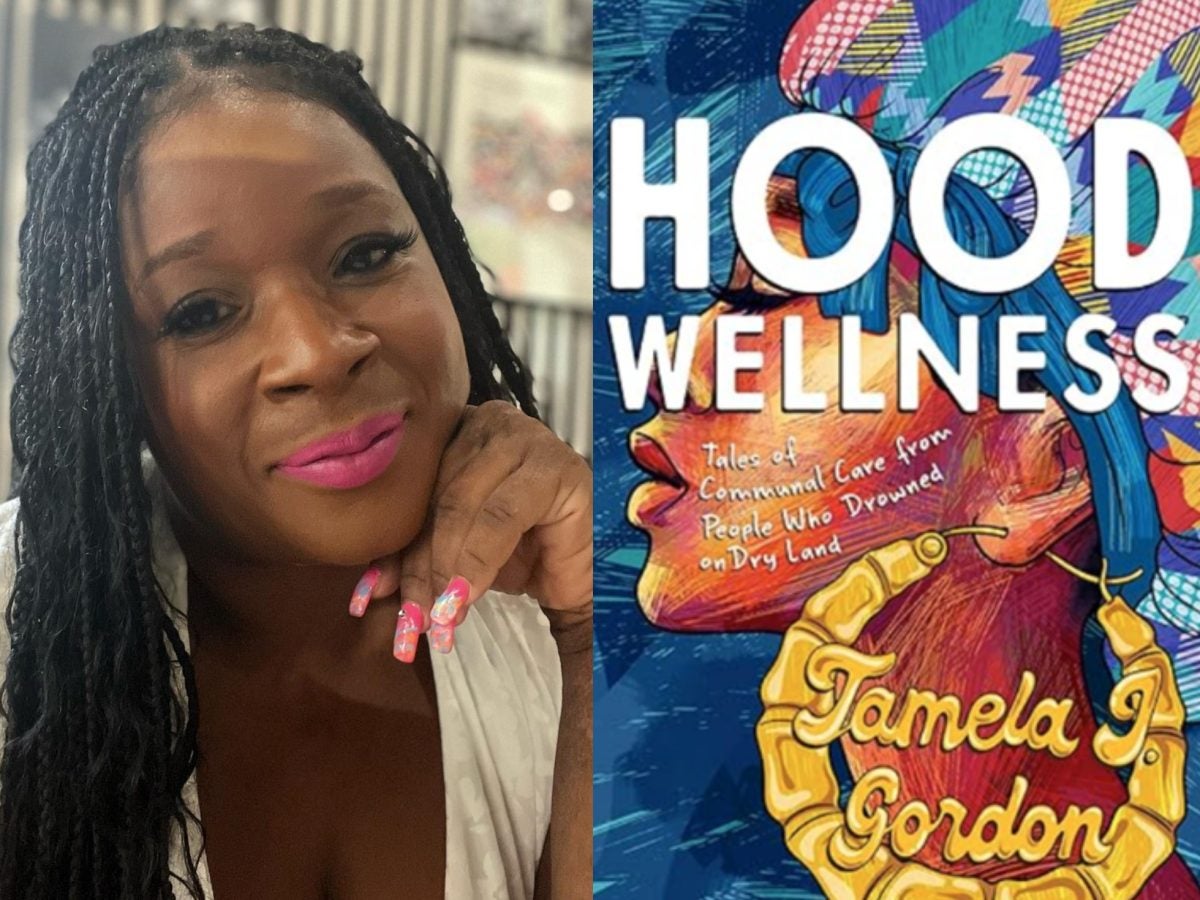

Gordon began being vocal about these disparities, first on social media, and then by writing what is now her debut essay collection, Hood Wellness: Tales of Communal Care for People Who Drowned on Dry Land. The more she wrote, the more she encountered others who were experiencing the same obstacles.

“There’s so much [shame], especially with dental care,” she says. “I’ll admit that, initially, I wanted to fix my teeth simply to blend in. While I didn’t feel tethered to vanity, I also understood the importance of having a healthy mouth.”

She adds, “I was hand to mouth and stealing food to eat, but when I found out I needed all of my teeth extracted, I needed to handle that by any means necessary. Dental health is a type of self-care that’s just as vital as rent or putting food on the table. I didn’t have the money, and I was ashamed to ask, but maybe my village could help.”

Family and friends raised thousands of dollars for Gordon to receive the proper care she needed. The experience of getting comfortable speaking clearly and eating with dentures was strenuous, and it would inform the work that became Hood Wellness.

In one of the essays in the collection, “Gummy B*tch,” Gordon examines the link between dental and sexual health. “I don’t mean to be gratuitous when it comes to discussions of intimacy, but at the same time, that’s a part of wellness too. I want anybody who’s like me to know what foods to eat with false teeth and be able to evaluate what intimacy looks like,” she says.

The journey to getting well for Gordon and people like her fills the short stories in the book in the hopes of encouraging other Black women and men.

“While I’m not necessarily 100% comfortable with divulging my sex life, dental care, or having conversations about my childhood, we do it because it’s part of the healing, and without that healing, we’re not going to get well,” she says, citing the significance of a particular essay, “drowning on dry land,” explores the ways collective trauma impacts personal wellness.

In the book, through her own testimony as well as through the experiences of others, Gordon yields the power of storytelling and emphasizes the significance of exchanging information when it comes to how we show up in community.

“We can’t get well if we’re not honest, and all of the models of wellness that we have up until this point are reliant on us ignoring the reasons we’re not well. But wellness, ultimately, is all of our needs and desires being met. That shouldn’t be controversial or too out of the box,” Gordon says.

“Black women, especially, belong at the forefront of these conversations about self-care. For the person who got a back tooth missing, for the woman who’s been celibate for eight years, for the individual who is suffering through chronic or terminal illness, I see you,” Gordon adds. “Healing gets a little messy and intense sometimes, but it’s necessary for the sake of our own personal wellness and for the community.”