This story is featured in the May/June 2022 issue of ESSENCE, on newsstands now.

For some, the quintessential all-American meal starts with a cheeseburger right off the grill and ends with a slice of apple pie. Maybe there’s even an ice-cold soda to wash it all down.

If you ask chef Kwame Onwuachi, that menu has a different look and taste: smoky Jamaican jerk chicken, spicy Trinidadian curry, savory Puerto Rican pollo guisado, fragrant Nigerian suya and even a bubbling pot of crawfish étouffée, by way of Louisiana. That’s because his America is less about what’s been modeled in idyllic ads and more about his lived experience as a son of the African diaspora.

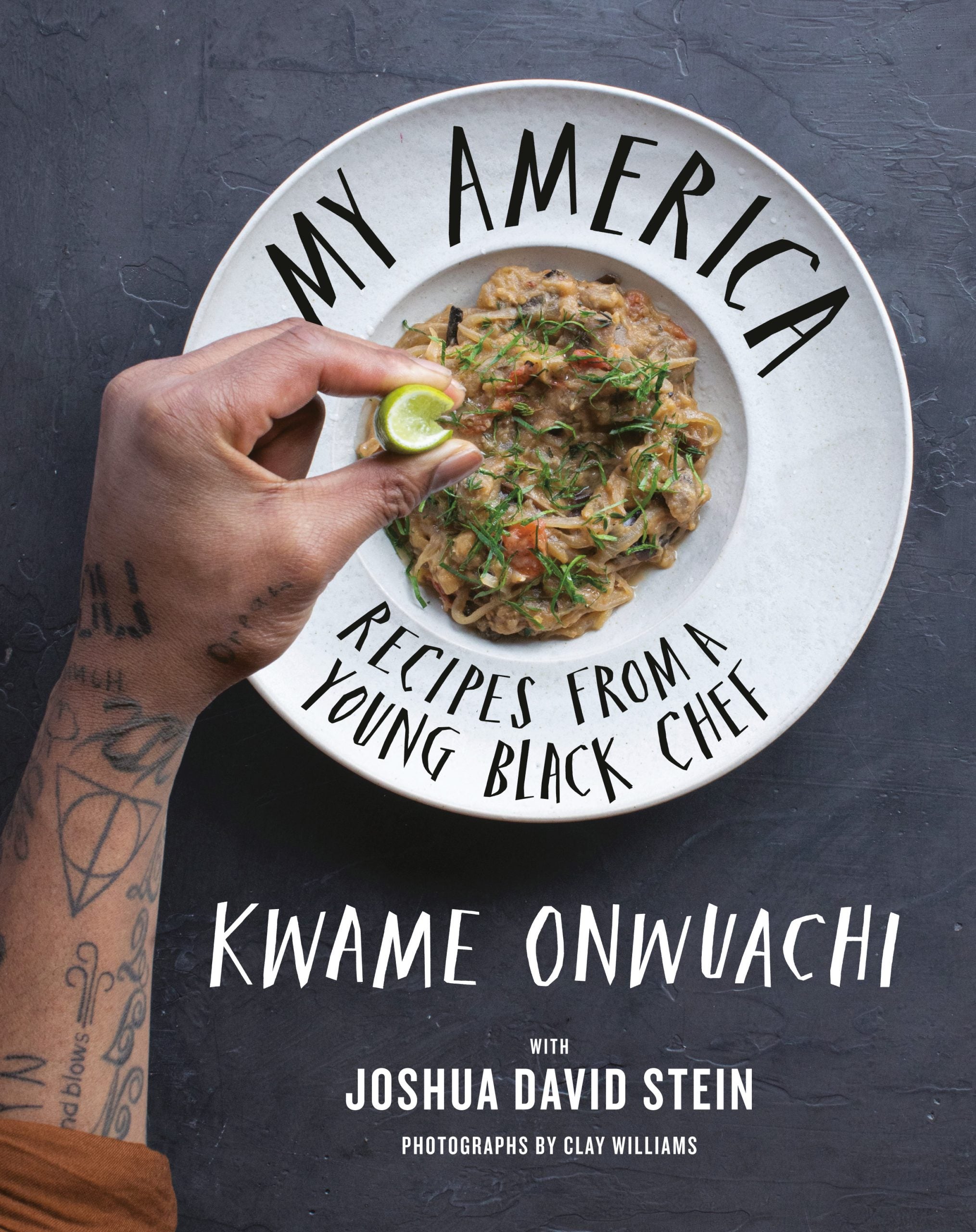

Onwuachi—a classically trained chef, restaurateur, James Beard award–winner and Top Chef judge—knows his way around a kitchen. But it’s his familial ties to Jamaica, Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago, and the American South that serve as the source for his first cookbook, My America: Recipes From a Young Black Chef, which was released this week.

“That’s why it’s called My America—it’s my version of American cuisine, how I saw it through my lens growing up here,” he says. “I wanted to showcase that, at the essence, these dishes are as refined as anything else, and they should be respected as such.”

Through the recipes in the book, he’s set off on an exploration of his ancestral kitchen. My America is a cookbook, but at times it reads as part history lesson, part personal memoir. This was intentional.

“I wanted to tell that story,” Onwuachi says. “[The food] tells the story of the slave trade. If you really read through these excerpts, you’ll understand where our people went, and the influence that we’ve had, and the tentacles that have gone across the world from the diaspora.”

The idea for the book came immediately after his memoir, Notes From a Young Black Chef, hit shelves. It also came as his star continued to rise. Last year he was appointed executive producer at Food & Wine magazine, balancing the role with a full calendar of TV appearances and events. In between all of that, he traveled to his family’s homelands to fully immerse himself in the food culture.

In Nigeria, he “ate and listened to the stories of the food.” He toured Jamaica, from Kingston to Negril. In Louisiana, he discovered where Mardi Gras rose to prominence. With his grandfather, he visited Trinidad and Tobago, stumbling upon a roti shop in the mountains on the way to Maracas Beach.

“They had every single type of curried filling to go into this roti,” he says. “Everything from liver to duck to lobster to conch to chicken to goat to pepper—everything.”

This kind of food, he says, is “wise,” with an inimitable story. The visit to that roti shop was a reminder for him of his purpose—for the cookbook and for his journey.

“I just thought, This is probably one of the best restaurants in the world, tucked away in this little mountain that no one really knows about—and that moment further enriched my duty and obligation to tell that story.”