I was a “library kid.” Nothing excited me more than visiting the branches around my city, rummaging through the ‘young adults’ section, and escaping to whatever journey a Goosebumps book could take me on.

As time progressed, the library became associated with forced work. College classes, study groups, and the dreaded team projects made the library a place to avoid.

Now, technology has given us audiobooks and digital downloads, making the appearance of someone holding a physical book seem avant-garde. However, with the normalcy of remote work, entrepreneurship, and even homeschooling, the positive affinity for libraries is returning. Across social media, there have been calls for people to trade their home office for a library study nook, support their local branch, and fall back in love with turning a page.

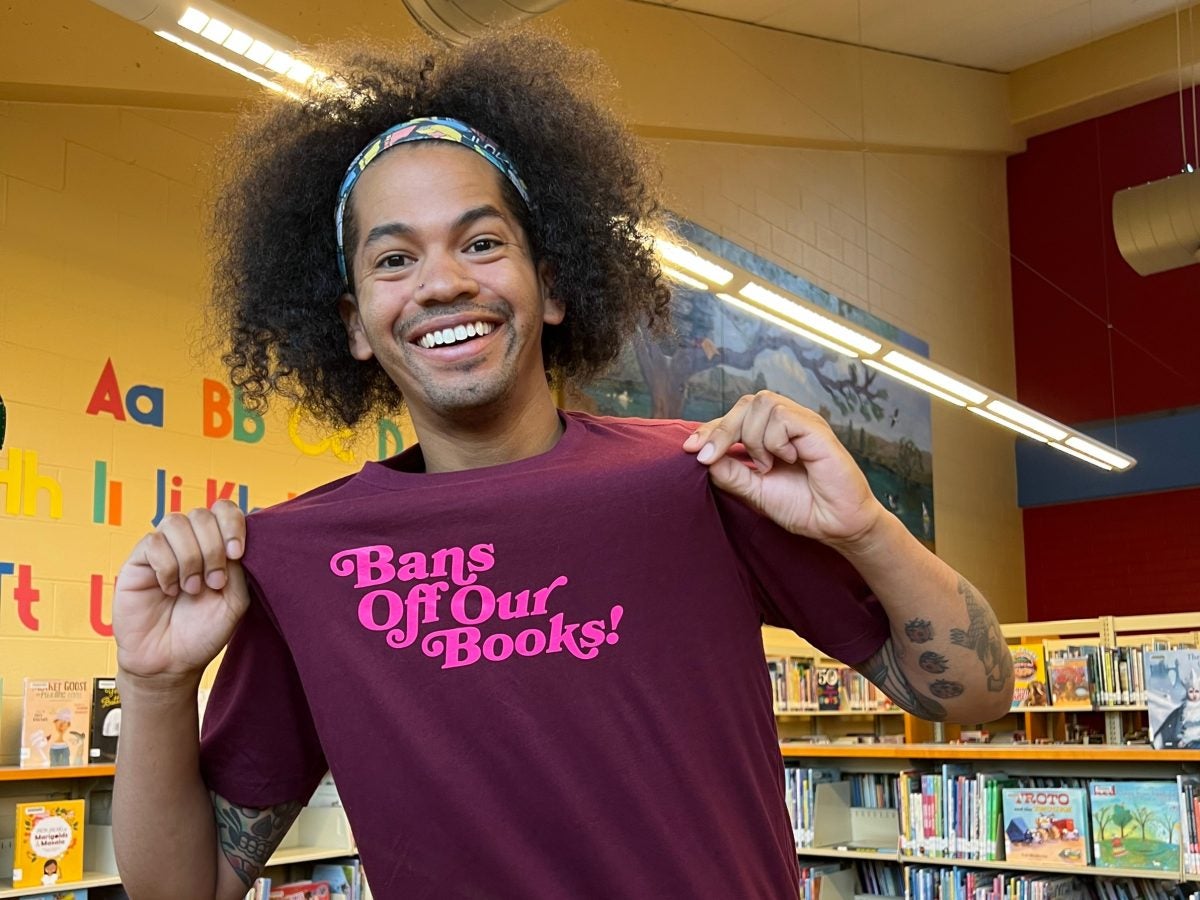

Mychal Threets, also known across social media as Mychal the Librarian, has become the guiding star for library advocacy and support. Hailed as “this generation’s Levar Burton,” Threets went viral for sharing uplifting moments he would experience as a librarian in Fairfield, Calif., for the Solano County Library. As a homeschooled student, the library was a classroom and more for Threets. “It was always a safe space,” he tells ESSENCE.

Threets’ earliest memories of his “safe space” ultimately influenced him to become a librarian. He began creating videos about his day-to-day interactions to meet people where they were and remind them of the library’s purpose. He aimed to show everyone that the two coincide even in today’s digitized world.

“People don’t realize how much the two collide and that there is a digital divide in the world but not so much in the library,” Threets says.

He added. “I think people forgot that the library is always growing, always enhancing itself.”

Libraries are free book havens and the cornerstone of inclusive learning. As Threets points out, branches provide “free in-person or virtual homework help” for students who can’t afford tutors, “free language courses,” and some offer “free legal assistance” from lawyers who provide pro bono services.

Physical and digital libraries are the go-to source for remote learning. Educators utilize built-in programs and teaching tools that automatically connect students to their local branches.

Digital databases such as Libby provide individuals with a nationwide web of libraries and directories at their fingertips. Readers can choose a book and pick it up at their local branch, creating a full circle of support.

Libraries receive funding through various sources, depending on the type of branch and its location. Typical sources are local government, donations, partnerships, grants, and implemented consumer fees.

While Threets is taking his advocacy to Washington D.C., introducing a multi-million dollar initiative to senators for funding, Atlanta-based librarian Forrest Evans has a simple answer for keeping doors open and shelves stocked with books for years to come.

“It’s money already spent. It’s your tax dollars already working for you,” Evans says. “So be amongst that circulation. That way, you are esteemed, seen, and heard.”

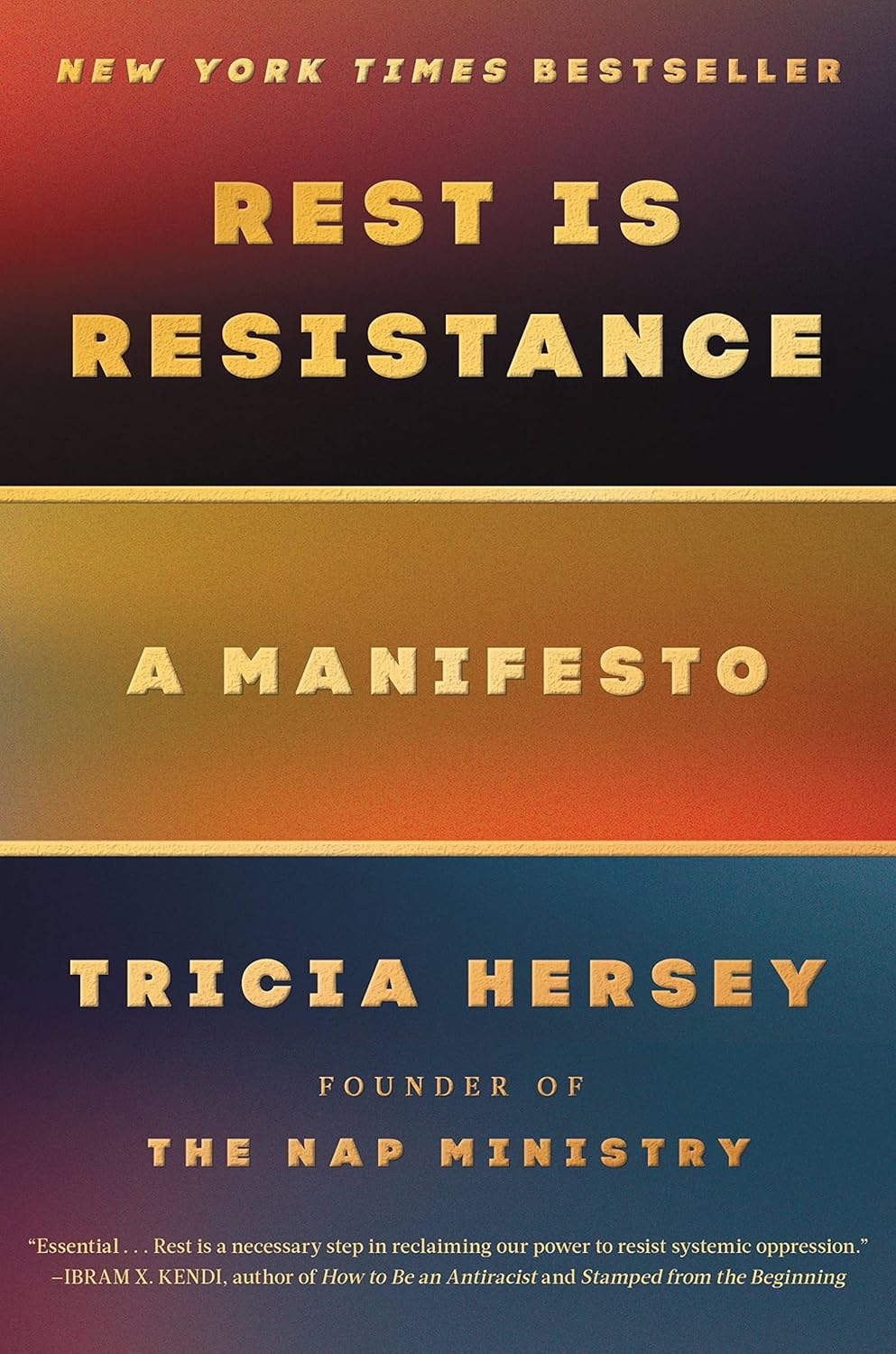

Evans’s urge for citizens to use what’s already in the budget is fueled by the uptick in the number of librarians and spaces being vilified for providing historically accurate texts in the book ban era.

“There are over 20 states right now that have Senate bills that criminalize librarians and media specialists if they circulate “harmful” materials, which is ambiguously vague in that bill’s writing. It proposes a new federal charge that would be a $100,000 fine, and you would have your license revoked or terminated,” she says.

The same conservative and supremacist efforts have been behind the erasure of Black history within textbooks and curriculums across the country.

Disparities in locations in low-income areas, minority-serving branches, and on the campuses of historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) take many forms, such as a lack of books, updated supporting materials, and Black and Brown media specialists who can create a welcoming environment for readers of color.

“Not only is there not proper funding that provides specifically underserved, under-educated minority-serving or women-started institutions, organizations or nonprofits – they’re not included in the conversation,” Evans notes.

She mentions that organizations such as the American Library Association (ALA), the Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA), and the Georgia Library Media Association are fighting to protect readers’ and librarians’ rights. But Evans says that ultimately, it’s up to the “individual professional” to advocate for their location’s needs.

“This is why representation is so important,” she states.

The value of libraries is evident in the people they nurture and the relationships that develop. Kayla Rayford, Aziza Kelly, Alex Brame, and Denisha Cranfield met as undergraduates at Bowie State University. The four, from various parts of the country and backgrounds, bonded over their love for reading. Their digital book club, The Reading Black Girls, represents what libraries can cultivate.

Kelly’s endless reading list, Rayford’s memories of her first library card making her feel as though she had the “keys to the world,” Brame’s summer reading program, and Cranfield’s science programs (memorably, with a python) are all small instances of how libraries promote lifelong learning and finding possibilities in between and outside of the pages.

“If you’re a library lover, you’re a book lover,” says the group’s co-founder, Cranfield. “I think that the library is always going to be a place where you’ll be able to find joy; you’ll be able to escape whatever reality is thrown at you. As book lovers, I know that’s kind of what we’re here for. Escapism. I think that libraries are essential.”