When it comes to kids and the COVID-19 vaccine, K. Elle Jones isn’t a conspiracy theorist. But a previous experience with mandatory inoculations has made her skeptical. “I do believe something happened to my child when he got two vaccinations very close together,” she says from her home in Riverside, California. “We ended up seeing him revert developmentally.”

To prevent severe illness or hospitalization from the coronavirus, the CDC currently recommends that everyone age 12 and older get a COVID-19 vaccine, within the scope of the Emergency Use Authorization. However, Jones isn’t convinced that vaccination is the right choice for 15-year-old DJ as he begins his freshman year of high school. “I don’t want my son to get ill as a result of him not being vaccinated,” says the director, producer, filmmaker and brand consultant. “But I’d never forgive myself if I did get him vaccinated and then, a year later, we find out all these different types of impacts.”

Ericka Sóuter, a parenting expert and author of How to Have a Kid and a Life: A Survival Guide, has heard both sides of the debate from moms like Jones. She encourages them to weigh two considerations. “Are they more afraid of an unknown, unproven, possible risk?” Sóuter asks, describing parents’ vaccine fears. “Or are they more afraid of the child getting one of the COVID variants and ending up in the hospital?” That said, Sóuter understands that it can be difficult for families to see the virus as a threat if they haven’t experienced anyone getting sick from it.

Cynthia Murray’s 16-year-old daughter, Paige has cerebral palsy and asthma; and for Murray, getting her the vaccination was a no-brainer. “My priority as a mother of a special-needs child was making sure she was safe,” she says. “I was concerned, and I wanted her to take the vaccine to be safe when she went back into school.” Meanwhile, New York mom Malene Brissett hopes the city won’t require students to be vaccinated. She has doubts, based on how quickly the vaccines came to market. Brissett understands the argument that the technology used was under development for years—and knows the vaccines underwent rigorous testing protocols. But she isn’t reassured: “I [believe] it required more time, but I know we were in a dire situation to find a solution to reduce the number of deaths.” Still, the mom of three and her husband are “85 percent sure” they’d vaccinate their kids if push came to shove—or figure out a remote-learning alternative.

Shots aside, her biggest concern is convincing her 8-year-old son, Jason— who was obsessed with pandemic news reports—that it’s safe to resume outdoor sports. One too many images of freezers storing dead bodies left him shaken. He now refuses to play football with his team and prefers the virtual universe of Roblox. “I’m unhappy that we have to drag him outside,” says Brissett, founder of Brooklyn WATE, a women’s empowerment group. “He cries, ‘Mom, can I just stay home?’ ” Brissett did finally convince him to take swim classes.

If Jason’s behavior seems extreme, Sóuter affirms that it’s normal, especially after being in a protective bubble for so long. However, she challenges parents to create opportunities for kids to comfortably engage with peers. She also recommends that parents communicate openly and effectively with teachers and coaches about testing, mask policies and other safety protocols. “We know kids perform better and have better outcomes when they participate in activities and clubs and are socialized,” Sóuter explains, adding that sports and extracurricular activities teach valuable skills like teamwork and compromise.

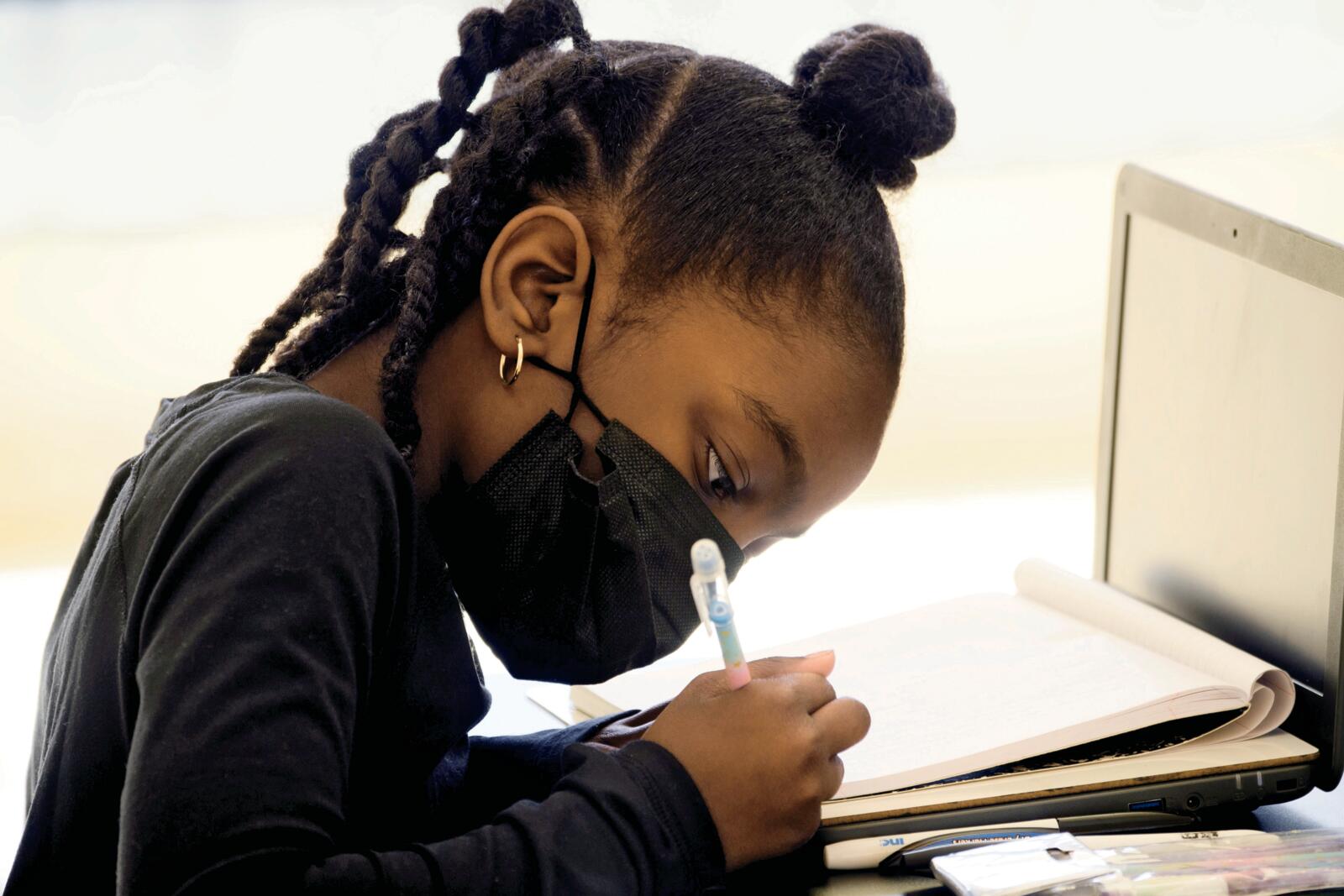

During the pandemic, both Brissett’s and Jones’s kids escaped into electronic devices. Pulling kids away from online gaming and tablets is crucial to getting them reacclimated to the classroom. After a year and half of remote learning, students around the country are being forced to play a wicked game of catch-up. That’s why Sóuter urges parents to make sure everything is in place at the start of the year, especially for students with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). “If you haven’t been approved for services—if you weren’t assigned a speech pathologist, reading specialist or whatever your kid needs—now’s the time to lobby to make sure those things will be put in place for your child,” Sóuter says. Brissett and Jones are already on it. Jason’s school scheduled a soft launch, with activities to help students adjust to the new classroom layout and to relieve any PTSD. And before DJ graduated from middle school the Jones family had a meeting with administrators and DJ’s support team at his new high school. While DJ is now eager to return to school, a few months ago, he wasn’t feeling it. “He’s excited about taking video production as one of his classes—and for the docuseries I do for my branding agency, he’s one of the producers and helps me run things on set,” Jones says with pride of his work on Beauty Behind the Brand Live Docuseries. “I think all this will make it easier for him to go back to school in the fall.”

This article originally appears in the September/October 2021 issue of ESSENCE Magazine