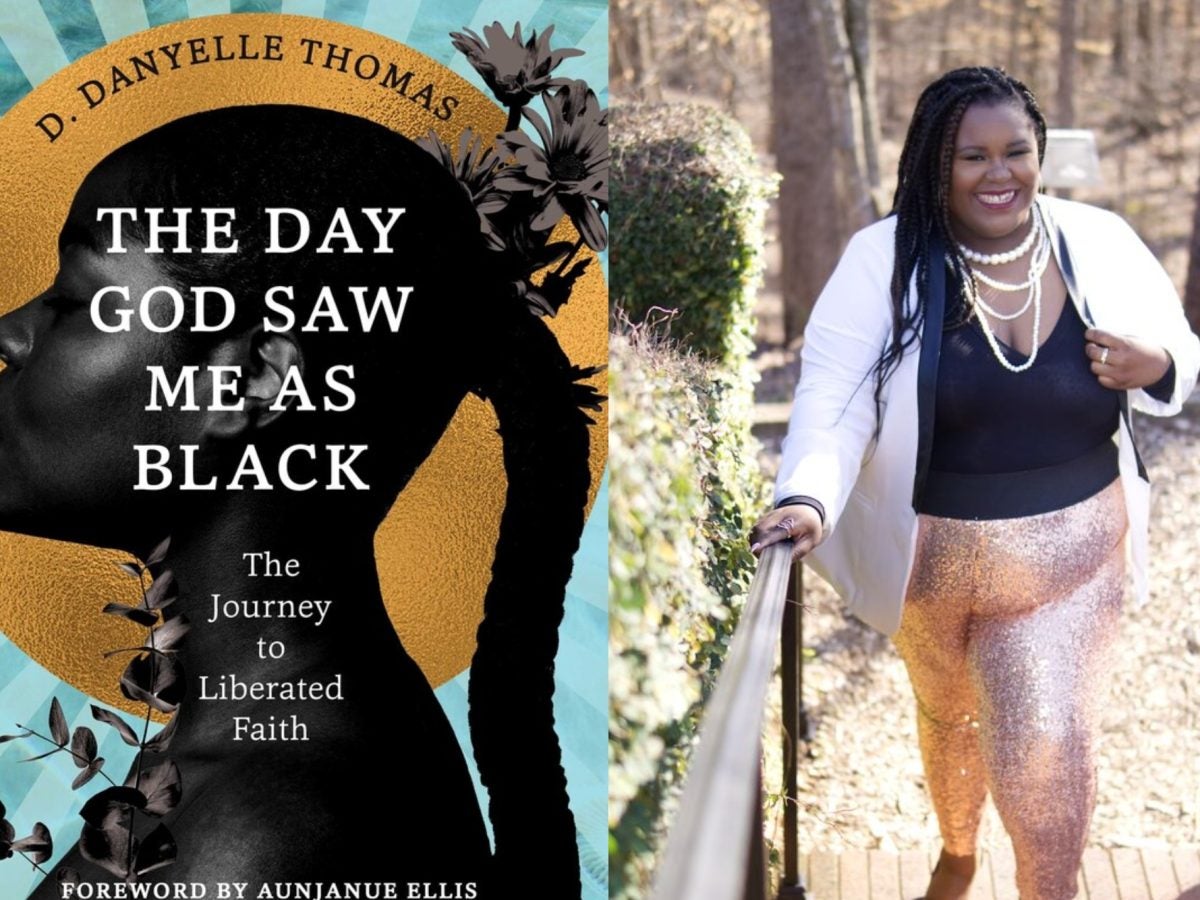

In the foreword of D. Danyelle Thomas’ The Day God Saw Me as Black, actress Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor writes an opinion that reads like more of a statement of fact: “Black folks made God good.” The saints will tell you that God is good (All The Time!) inherently. But that goodness wasn’t reflected in the version of God European colonizers offered. Ellis-Taylor continues by saying that Black folks gave God song and morality and made God beautiful. She writes specifically of the unseen and uncelebrated work Black women have done in the church that often relegates them to the background away from the pulpit and the power.

But in The Day God Saw Me as Black, Thomas, a public theologian and founder of the digital faith community Unfit Christian, invites Black women, Black queer folks, and Black nonbinary people to consider a God that sees and loves them in their fullness. It’s a book for those who have been mistreated or marginalized by traditional church spaces and are looking to feel more seen and more free in their relationship with God. Thomas begins with sex.

“I do believe that the body is the first site of liberation,” Thomas tells ESSENCE. “If you’re not free within yourself to be your whole self, there is nothing you can do to contribute to the work of liberation.”

Thomas argues that we expand ourselves when we articulate and define what sex is to us outside of what someone told us. Something as simple as thinking about your body and your pleasure can usher you into the work of considering other oppressive ideals we may have adopted along the way.

“You begin to understand that is where we are all attacked,” Thomas explains. “All laws are governing the body. So when you become free in that space, you understand that you belong to you. In order to maintain your own belonging, you have to protect that for everybody else.”

For Thomas, everybody else includes queer and same-gender-loving people who have been and remain the most ostracized in Black churches around the world. She connects their present-day malignment to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade.

“The enslavement of Black people built this country’s wealth. But it wasn’t necessarily the plantation labor,” Thomas says. “Black wombs are the most profitable things in this country. It is why there were plantations specifically for breeding. So when you have this idea that being same-gender loving or queer in any way is a sin, you have to ask why. It comes down to reproduction and sex. It is because they can’t produce life. They can’t produce the life that then produces the labor that then produces the income.”

Black people and Black churches guided our own internalized racism and have felt animosity toward Black, queer, trans and same-gender-loving people because in addition to the “problem” of Blackness, there is the additional layer of sexuality or gender identity acting as an additional barrier of acceptance by white people.

“These folks are so bound in the idea that their bodies are inherently sinful that they are constantly in pursuit of what will make them holy,” Thomas says. “But you are already holy because you are created in the image of God and you’re not striving for holiness.”

The hostility directed toward the LGBTQ+ community, she says, can be attributed to the fact that the church focuses so singularly on the sex between consenting adults that they’re not considering the love they may have for one another. Thomas writes that even the church’s view of love is skewed. In the book she states that the church traditionally has not been able to conceive of love where one party is not controlling the other.

“I talk about this abusive relationship that I was in in this book,” Thomas says. “My teaching, not even about sex but about love, led me into a space of tolerating verbal and emotional abuse that had I been taught better language around love, I would have chosen differently.”

Women specifically are taught, through the church, to love unconditionally. But Thomas posits that some love should absolutely be based on the conditions that you’re receiving what you need and are being treated well. These teachings about long suffering and forgiveness can lead to confusion on what a person should or shouldn’t accept in relationships, including various forms of abuse.

Many Black women growing up in church received clear marching orders on who they were supposed to be and how to behave. The same is not entirely true for men. Thomas says men are learning from the silence.

“In the absence of the message, you assume the lesson,” she says. “What message is the church sending when we masculinize God, as the church often does? God is this powerful, indiscriminate being who will strike down and kill anything that disrespects–a jealous God. And we wonder why women tend to view a man’s jealousy as a form of love.”

Thomas wishes the church would point to Jesus, God’s son in the flesh, as an example of how men should treat and advocate for women.

“Jesus uses his paternal, patriarchal power to protect a woman,” she says, referencing the adulterous woman who a mob planned to stone to death. “Why are we not emphasizing that when we talk about what it means to be a man?”

In The Day God Saw Me as Black, Thomas also addresses the errors of women who’ve attempted to align themselves with the patriarchy as a means of acceptance and power in the church. She writes specifically about Juanita Bynum and her famed sermon “No More Sheets.”

“I watch her give this sermon about all the ways Black women need to perfect themselves, and she offers herself as an example of someone who has done this work,” Thomas says. “She gets the prize. She gets married and he’s beating on her in the parking lot of a hotel in Atlanta. She still becomes a victim. I see a woman who, despite serving patriarchy, did not win its end game. You’re never going to win this game because they’re always going to move the goalpost. That’s with Black women and misogynoir. That’s with Black folks and white supremacy. That’s with queer folks and cisgender heteronormativity. They’re going to constantly move the goalpost because the objective is to maintain power.”

Still, she offers Bynum grace. “Despite the numerous harms I think she has inflicted upon us, I know that had it not been for the Lord on my side–if it had not been for me doing my own work, I would be her,” Thomas says.

The Day God Saw Me as Black highlights the ills of the church. But as she grows and expands in her new spirituality, Thomas wants to move beyond enumerating the problems with the Black church to imagining what the church could be in the future.

“I want to see the church as a communal hub to take care of the people around us without attaching membership to it, without attaching salvation to it,” she says. “I feel like if you show up as the light, people will be drawn to the light.”

And for those who may be seeking a relationship with God outside of the four walls of the church, she offers these words.

“You really can have your faith be one that reflects the totality of who you are,” Thomas says. “You don’t have to be loved by God in pieces. You have a God that sees the whole of you.”

The Day God Saw Me as Black is out now.