This story originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of ESSENCE

When Victoria Walker bought a DNA testing kit in December 2017, it was to join her family in finding out more about their ancestry. Growing up with a great-aunt who had been the family historian for decades, Walker, a Washington, D.C., attorney, already knew a few details about her mother’s side. She knew, for example, that her mother’s family hailed from Louisiana, but beyond that, the geography was sketchy. “I probably knew no more or less than other people from the South,” says Walker. “The DNA test added another level to our history, one that my great-aunt, in particular, was curious to find. She definitely encouraged us to take the test.”

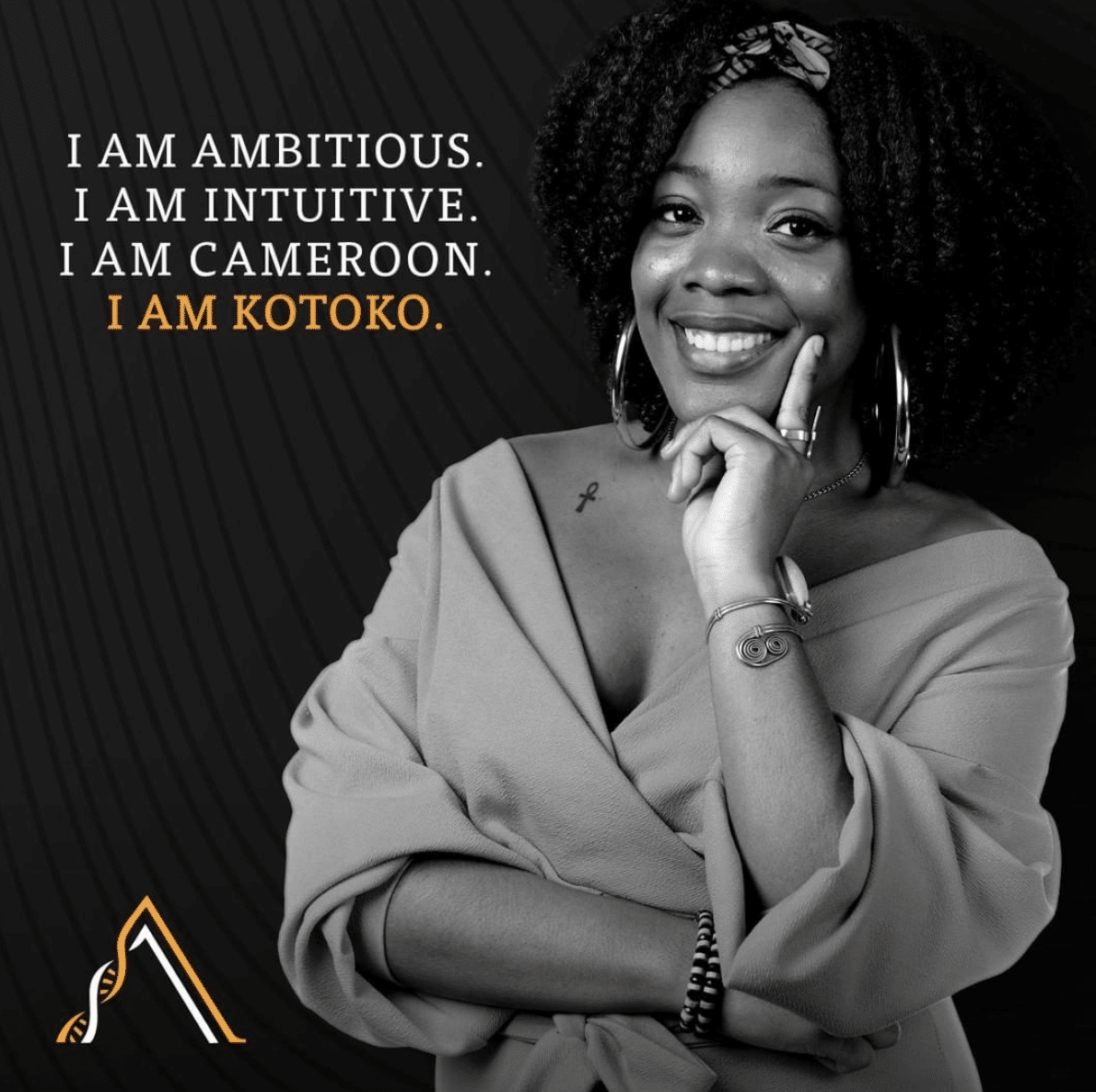

Walker, who used a kit from AncestryDNA, is among hundreds of thousands of African-Americans who have turned to technical advances in personal DNA testing to uncover a critical piece of a heritage lost through centuries of forced migration and slavery. “As people of African descent in the diaspora, particularly in the Americas and the Caribbean, we are the original victims of identity theft,” says Gina Paige, cofounder of African Ancestry, which has helped more than 500,000 people trace their roots to specific countries and even specific ethnic groups on the African continent. “We lost our names, we lost our languages, we lost the freedom to honor our ancestors, and our families were torn apart.” Paige and other experts point out that not all DNA testing kits are the same, nor can they all cater to the particular needs of our community.

THE TEST

By using genotyping, researchers at consumer DNA testing companies such as AncestryDNA, African Ancestry, My Heritage and Living DNA are able to assemble a comprehensive report on a person’s genetic makeup. The scientists then compare it with a larger set of DNA samples to discover that person’s family tree, ethnicity, geographic ancestry and genetic health markers.

Each firm’s DNA data set is unique, however. In general, the larger a company’s data set of people from Africa or of African descent, the more specific it can be in pinpointing where your ancestors originated. Because the databases of many companies are drawn from samples that are mostly of European descent, this data could be the difference between Black folks finding out that they are broadly from West Africa or that they come from a particular modern-day country and ancestral tribe.

The type of DNA that a company chooses to analyze is another key factor in the results you’ll receive. Y-DNA tests will trace paternal lineage but can only be taken by males, since women don’t possess the Y chromosome; mtDNA tests track maternal lineage; and autosomal DNA tests can trace both sides of your ancestry but won’t go back as far in time as the tests for paternal and maternal lineage.

The more specific you are about what exactly you want to find out, the easier it will be to narrow down the best company and type of test to use. Ronique Williams-Gordon was born in Jamaica and now calls Toronto home. She wanted to include genetic health screening when she had her DNA tested, so she chose to go with 23andMe. But she admits she might have gone with a different company if she’d solely wanted to learn about her ancestors’ geographic heritage. “I wanted to know which part of Africa I am from so that I could tell my children and have a sense of pride and purpose,” she explains. ”But I also wanted the health part to see if there was information I needed to know.”

THE DETAILS

If you’re interested in DNA testing, be aware that it can come at a cost that is not yet clear. Many people have called on the Federal Trade Commission to complain about the privacy practices of consumer DNA testing establishments. Each company has clear guidelines on how it plans to use your DNA after initial testing, and it’s critical that you read and understand what you’re agreeing to.

Walker did read the fine print, but wondered if she should have weighed it more carefully when she read news stories of how police investigators were able to find the Golden State Killer in 2018 by matching an old crime scene DNA sample with the DNA of the killer’s relatives that existed in public databases. Other people aren’t really concerned about the privacy issues—“To be honest, I don’t care,” says Williams-Gordon—but Nicka Smith, a family historian with AncestryDNA, advises that people take the extra step to research the companies’ privacy policies. “People should be concerned,” she says. “We need to ask, ‘Where is my data going? Do I have control over it?’ ”

THE RESULTS

It’s not just the obscure restrictions that customers need to consider, it’s the results themselves. That’s because DNA testing can help you dig up the information you are searching for—and the information you aren’t. The uncovering of family secrets can follow in the wake of testing, for example, including the discovery of illegitimate children. According to Smith, Black people are also often surprised by how little African ancestry we have as well as by how little Native American blood actually runs through our veins.

“None of us in the Americas is 100 percent African,” notes Paige. “So when we’re tracing just one branch of the tree, we don’t know if that result is going to go back to Africa or if it’s going to go back to Europe.” Based on 16 years of research at African Ancestry, Paige estimates that the average African-American person is 75 percent African and 25 percent European—a breakdown that some of us can struggle with, because it is direct scientific proof of the horrors of slavery. “The history that is associated with the reason why our ancestry may have European roots is a painful one that many people aren’t necessarily interested in exploring,” says Paige.

But some DNA testing discoveries can open new doors to the past. Williams-Gordon was happy to learn that she has 90 percent African ancestry, 40 percent of that from Nigeria. She plans to make Nigeria the first country she visits in the Motherland. Her result points to the ultimate power of these tests for the people who take them: It lies in the knowledge of self and family that is gained. Says Paige: “You don’t really understand the impact of not knowing until you know.