“She won’t become anything.”

“She’s damaged goods.”

“No one will want her.”

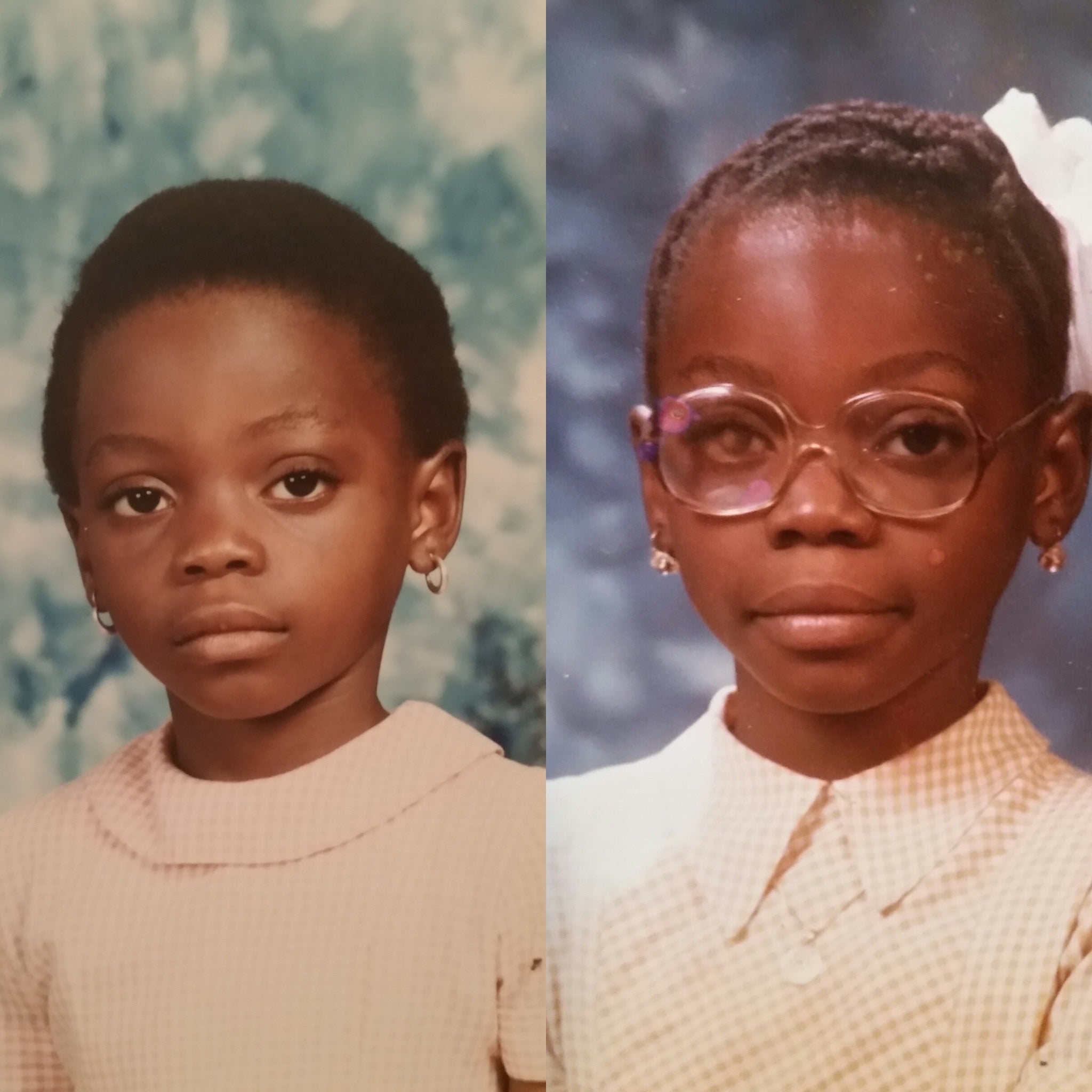

These words were spoken to my devastated mother after I had been rendered blind in my right eye at the hands of her dearest friend. I was only seven years old. This single moment in my childhood both altered my life forever and informed my journey to becoming the woman I was meant to be, and it was inextricably rooted in the socio-economic strife that plagued my homeland of Haiti.

Years earlier, my parents had ventured from the countryside of Haiti with nothing more than a middle school education to find livelihoods in the capital city, Port-au-Prince. They married and settled in a small two room house where my brothers and I were born.

When my father lost his job as a factory laborer, my mother bore the burden of supporting us with the meager monthly salary of $150 that she made housekeeping. The scarcity of employment opportunities in the country for so many working-class women and men coupled with the pervasive oppression and civic unrest under President Francois Duvalier’s militant regime (1957-1971) and then his son’s Jean-Claude Duvalier (1971-1986) led my father to join the growing exodus of Haitians to America, where the displaced diaspora could earn enough money to support their families back home.

And so, my mother made the fateful trip to visit my father in America that necessitated her to entrust my care to her friend. One afternoon, my mother’s friend accused me of fiddling with the old sewing machine my mother used to perform extra work as a seamstress. My fervent denials did nothing to spare me from a spanking with her belt. The prong from the belt’s buckle struck my eye but she didn’t believe my anguished cries. It wasn’t until the next morning when she saw it, sanguine and swollen shut, that she realized something was terribly wrong. She kept me secluded at home for three days, placating me with saltwater compresses in the futile hope that the swelling would subside. The color partially faded from my iris. By the time I was taken to a doctor, it was too late. Due to internal bleeding for three days, I had lost my vision. Lost, too, was the outgoing, playful child I’d once been. The emotional trauma left me fearful and distrustful of people.

A woman of profound faith, my mother refused to accept my prognosis. In the ensuing days she took me to a slew of doctors for a second opinion. All came back with the same diagnosis. We sojourned in the mountains above Port-au-Prince to attend midnight prayer vigils where she implored God for a miracle. Perhaps wanting to give my desperate mother a bit of hope, one well-intentioned doctor advised her that if she could get me there, maybe a specialist in America could help me to see again.

In many Haitians’ eyes, America represented a promised land where anything was possible. I had dreamed of living here but had not anticipated the harsh reality I would face. I didn’t speak English, nonetheless I understood my thrift-store clothes and physical appearance were the reasons for the laughter and scornful expressions of the kids at school. I also began to understand racism, something I hadn’t dealt with in Haiti because there most everyone bore the skin colors of the warrior foremothers and forefathers who had waged a twelve-year battle against the European empire that held them in bondage to win our freedom.

More disappointment came when none of the American doctors could reverse the damage, and so I spent my formative years as the strange looking Black girl with big glasses and a discolored eye. Eventually, severe pain from increasing pressure required enucleation surgery to remove the eye and replace it with a prosthesis; still, the miracle to restore my sight that my mother had always prayed for manifested in a different way. It wasn’t until recently that I came to see that there was a greater purpose in what had happened to me that was beyond me—I was being called to share my story in humble service of anyone seeking a way through struggle.

I’d learned to navigate an unfamiliar world and endure ostracization because of my affliction and ethnicity. I’d refused to accept the existence of higher education as a privilege instead of as a right, and secured a college degree that would serve as the launch pad for my career in publicity. The obstacles persisted, but so did I. I was passed over for a promotion after it was mistakenly assumed I ignored the presence of colleagues due to an impersonable nature. In truth, a consequence of my partial blindness was I couldn’t always see them. Being perceived as weak made this an especially challenging revelation to share with my boss. I never used it as a crutch and assured her I would make the added effort to be more mindful. That dedication paid off with a 22-year career that led to my current role as Vice President, Communications at NBCUniversal, but it was my prayers to God that helped me to persevere as I kicked down doors and made moves to become one of the few Black women P.R. executives in the entertainment industry. Although my beginning was marked by tribulation, my life is about triumph.

If you’ve had to endure with a part of yourself missing, I am you. If you left your homeland and everything you’ve known in search of the American dream, I am you. If you were made to feel that you wouldn’t amount to anything because those around you saw only what you lacked instead of the God-given gifts you had to offer, I am you. I offer myself as testament of what is possible when you let nothing stop you from going after whatever it is that calls out to your heart – even when all odds are against you.

For your circumstances do not dictate who you become in this world—you do.

Sandra Lajoie (@lajoiesandra), is currently writing her memoir, Through My Eyes: My Journey of Defying the Odds. She plans to donate proceeds to PRODEV school in Haiti. Lajoie lives in Brooklyn, NY.