This story appears in the January/February issue of ESSENCE, on newsstands now.

Amid economic turmoil, political unrest, public health crises and general global strife, love—especially Black love—is a grounding force.

Every time we express love, we honor our ancestors who dared to love deeply and fearlessly. Even with the threat of being forcibly separated from each other, and with the inability to establish comfortable homes, our people embraced one another, with the singular faith that things wouldn’t always be so bleak. Their decision to make room for hope and warmth has grounded and sustained us.

I’ve experienced the full spectrum of Black love—from arranging flowers with my grandmother in her backyard to riding with my father on his tandem bike in the afternoons to catching up with my mother on our daily homegirl phone calls. I also know love’s more difficult side, as I embarked on the merry-go-round of a romantic relationship that often left me riddled with despair. I’ve listened to a lot of Keyshia Cole and Toni Braxton. Two tracks, specifically—Keyshia’s “Shoulda Let You Go” and Toni’s “I Love Me Some Him”—helped me navigate my emotions, heal and, later, self-soothe. After surviving the highs and lows of Black love, I know it intimately; and the familiarity deepens my appreciation.

Now, make no mistake, it’s work. Lord, it’s work. Consistently choosing someone can get difficult, especially when egos come out to play. But that’s just the thing: It’s a choice. You wake up every day and decide to love on your mate. Even though painful love may be a thing of the past, we can’t pretend like some days aren’t get-out-of-my-room-and-hit-the-sofa type days, with a you-a-mess cherry on top. Still, we show up and try again, because the I-need-us days outweigh all.

Aside from encompassing strength and resilience, our love can also be intentionally tender. Although Black love can be complicated and nuanced, at its core it is joyful. Even in terrible times, it is luminous, forcing out the grim realities of being Black in America and bringing the light. Today, as we honor the past and create space for the future, we count all the ways in which we continue the legacy of Black love.

JUMPING THE BROOM

Black couples have been engaging in this custom at weddings since the 18th century. Tyler D. Parry, Ph.D., the author of Jumping the Broom: The Surprising Multicultural Origins of a Black Wedding Ritual, noted that our enslaved ancestors weren’t free to marry legally, so many adopted the tradition of jumping the broom. As Parry shared in a 2022 New York Times article, this rite was once practiced by marginalized communities in Europe. It was later introduced to enslaved people in America by White plantation owners.

In The Journal for Southern Living, Patrick W. O’Neil includes a chapter called “Bosses and Broomsticks: Ritual and Authority in Antebellum Slave Weddings,” which observes that most slave owners used the broomstick to deem Black marriages transitory and unimportant—and to assert authority and dominance over enslaved households. But for us, jumping the broom signifies a new beginning; sweeping out the old, if you will. It respects the families of each partner while acknowledging the holy union the newlyweds have undertaken.

Over the past several hundred years, the tradition has endured; it is still a feature at Black American nuptials. After the newlyweds exchange vows and kiss, they hold hands and jump over a broom to seal their union. A family member can make the broom, or it may be an heirloom passed down through generations.

My mother was the designated broom creator for jumping-the-broom rituals in our family. I’d watch her meticulously apply white and silver ribbon, custom-made satin bows and fabric to the broom handle. She would then adorn the broom’s base with dried lavender, pearls and eucalyptus. It usually took her three days to decorate it. With pride, she would deliver her creation to the bride and groom, hopeful their love and bond would be eternal. For Black families today, jumping the broom marks the leap of faith needed to embrace Black love fully.

PAYING FOR A FULL SET

Black nail art can be traced back to 3000 B.C., with Queen Nefertiti painting her fingernails and toenails red to mark her royal status. According to Nails: The Story of the Modern Manicure, some Egyptians adorned their nail beds with artificial extensions made of ivory and bone. These days, getting our nails done serves as a rite of passage to womanhood. Every Black girl who has stepped into a nail salon remembers the first time she went with her mother, grandmother or auntie. Having the creative autonomy to select nail designs that are true to you is liberating—each design encapsulates a specific cultural aesthetic while accentuating Black women’s personalities.

But if our nails make a personal statement, that declaration can be rather pricey. A full set of gel nails, for example, can easily go for $50. So when someone pays for a complete set of nails for us, it demonstrates love—by honoring our culture and accepting our creative choices and personhood.

WEDDING RINGS

Wedding rings are an emblem of devotion. The symbolism behind them has much to do with their circular shape, which represents wholeness and timelessness. Circles have no beginning or end and, like love, are limitless.

As with nail art, ancient Egyptians pioneered the wedding ring. They believed the band represented eternal life, love and, ultimately, a spiritual portal. Thus they would exchange rings of love made of woven reeds or leather.

COOKING SOUL FOOD

Soul food is a staple in Black households. We whip it up to celebrate special occasions—or just to encourage togetherness among family and friends. From collard greens and macaroni and cheese to candied yams, cornbread and catfish, each dish proves that the way to anyone’s heart is through their belly.

In his book Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America, Frederick Douglass Opie points out that our enslaved ancestors in the South had to make do with the food provided, which influenced our current eating traditions. The rations usually included discarded meats or dairy products—nothing could be wasted. They decided to take those scraps and create a phenomenon. With modern soul food, we celebrate our foremothers’ culinary creativity. Out of great struggle has come wondrous innovation. With each intentionally crafted plate we fix, we deepen our love and respect for one another.

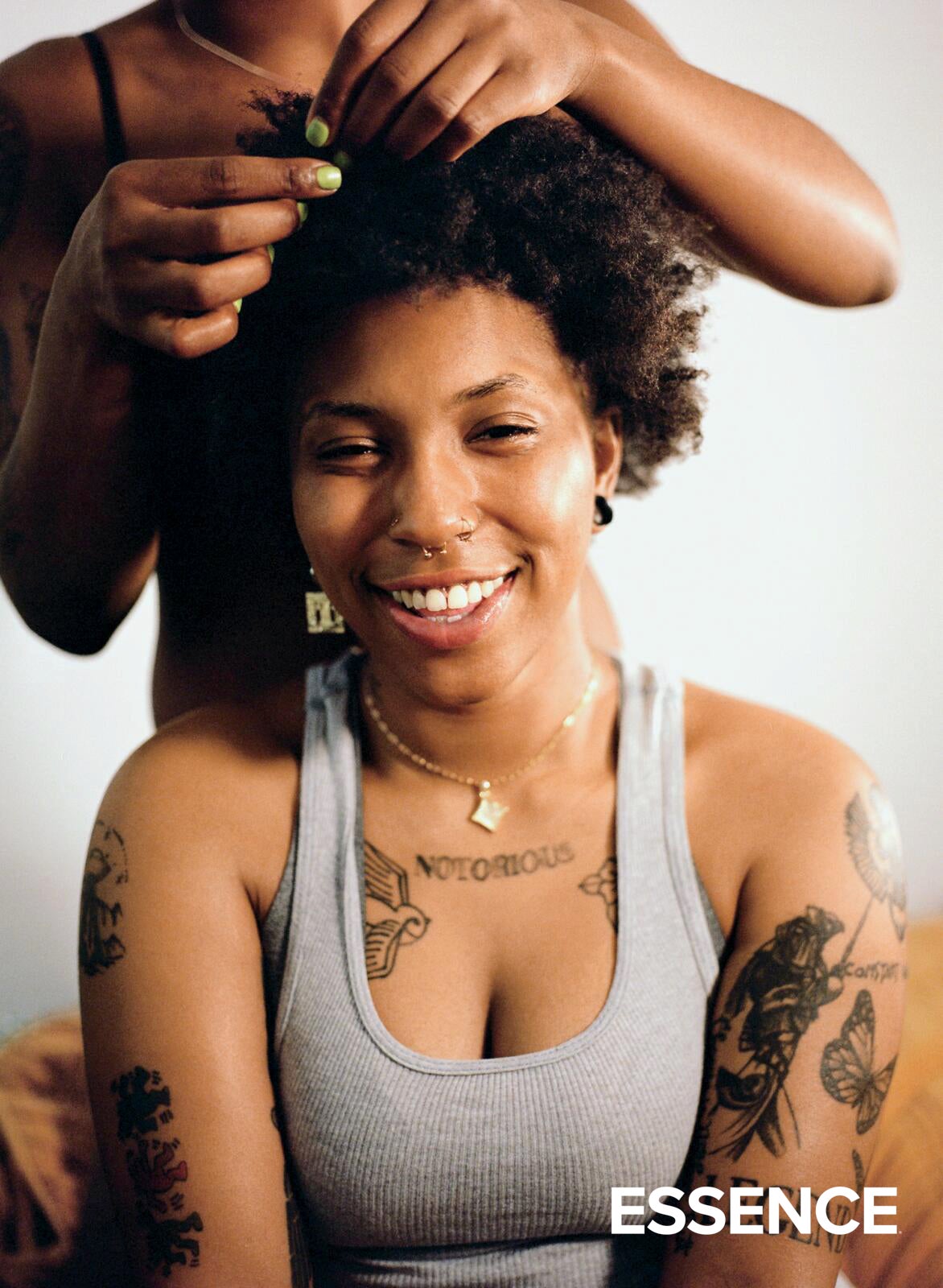

GREASING THE SCALP

Nature’s Blessings was the name of the hair pomade my mom used on wash day every Sunday. It was emerald green and smelled like a mixture of rosemary, sage and peppermint. After blow-drying my hair, she would sit me in the kitchen, pull out a mustard-colored rat-tail comb, part my hair into sections, and then grease my scalp.

This was a sacred ritual for us. Every week would be the same routine. There was a sense of closeness and intimacy as my mother applied the grease to my tender head and smoothed my edges. It was a loving gesture, meant to nurture the health of my hair. Many Black kids experienced the same custom growing up.

Without access to their usual herbal regimens, our enslaved ancestors were forced to innovate new treatments that would moisturize and protect their hair from harsh weather conditions, fleas and parasites. Many of them used bacon grease on their scalps. Centuries later, Madam CJ Walker created a pomade that was a modernized version of the hair grease our ancestors had invented. Her 20th century scalp-healing formula led to hair grease developing its own identity and category—and generated a market for a Black beauty boom.

Similar to braid take-downs, hair greasing, as it relates to romantic love, can be artful and sexy. Your partner not only signs up for an act of service but shows their willingness to see and accept you in your most bare state. It’s an invitation to deeper connection through a private act of intimacy, one that can be erotic even. Black women don’t play when it comes to our hair, and for us to trust our partners with helping to care for our tresses means everything.

LIBATION CEREMONY

Although wedding ceremonies are joyous, they can also have an air of somber reflection. As partners celebrate their union, they also honor deceased loved ones who passed away before the special day. Through a libation ceremony, Black couples pour out a liquid as an offering to a departed person’s spirit, deity or soul.

The observance isn’t limited to weddings and romantic ceremonies. Spiritual-libation occasions are often held among close friends to honor loved ones who have passed on. On Tupac’s 1994 track “Pour Out a Little Liquor,” he describes how he’s choosing to remember his lost friends and family by performing this rite.

This tradition exists not just in our communities but globally. It is practiced in Africa, Israel, Greece, Rome, Asia and South America, to name a few cultures that share in the ritual. As with all expressions of love in action, the libation ceremony is a call for uniting. In this case, the deceased and the living unite again through love.