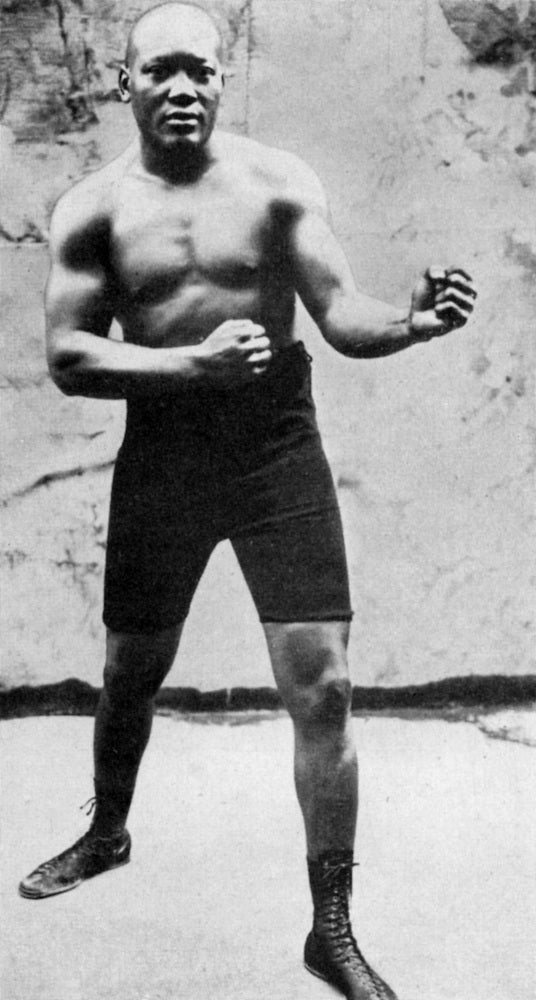

Thursday, Donald Trump posthumously pardoned Jack Johnson, the first Black man to become heavyweight champion of the world in 1908.

“Today I’ve issued an executive grant of clemency, a full pardon, posthumously, to John Arthur ‘Jack’ Johnson … The first African-American heavyweight champion of the world, a truly great fighter. Had a tough life,” Trump said during a ceremony in the Oval Office.

In true Trump fashion, America’s chief executive did not know about Johnson’s harrowing story until he was approached by Rocky creator, Sylvester Stallone, back in April.

“Sylvester Stallone called me with the story of heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. His trials and tribulations were great, his life complex and controversial,” Trump tweeted last month. “Others have looked at this over the years, most thought it would be done, but yes, I am considering a Full Pardon!”

On Thursday, Trump called clearing Johnson’s name “very important.”

“We have done something today that was very important, because we righted a wrong,” he said, surrounded by Stallone, current heavyweight champion Deontay Wilder, former champ Lennox Lewis, and Johnson’s great-great niece Linda Bell Haywood. “Jack Johnson was not treated fairly, and we have corrected that, and I’m very honored to have done it.”

While sports historians know all about Johnson’s larger-than-life personality and how the racist justice system ruined his career, others may not have heard about the storied boxer until now. So, here are 5 things you should know about Jack Johnson.

Johnson’s parents were born into slavery

Though he would rise to become the first Black heavyweight champion of the world, the deck was stacked against him from the beginning. Born in 1878, Johnson’s parents, Henry and Tina, were born into slavery and struggled to make ends meet for their large family.

He started boxing at 16

Johnson dropped out of school as a teen and worked a series of odd jobs before taking a job at a race track exercising horses. After meeting Walter Lewis during one of his gigs, he took up sparring. At 16, Johnson moved to New York City and once again worked at a track before reportedly being fired for exhausting the horses. He then got a job as a janitor at a local gym and saved up enough money for his first pair of boxing gloves. He would go on to make his professional debut at 20, with a fight in his hometown of Galveston, Texas against Charley Brooks.

The “Galveston Giant” became the world heavyweight champion in 1908:

Nicknamed the “Galveston Giant,” Johnson attempted to challenge for the world heavyweight title for years, but was turned down by white champions who were afraid of his powerful punches. On December 26, 1908 he finally got his chance against Canadian boxer Tommy Burns, in Sydney, Australia. The fight lasted 14 rounds, and in the end, Johnson was declared the heavyweight champion of the world, the first Black man to hold the title.

“The Fight of the Century” sparked riots across the country

So many white people were upset Johnson was the best boxer in the world they pressured former heavyweight champion James Jeffries to come out of retirement to challenge the brash Black champ. Dubbed “the Fight of the Century,” Johnson faced Jeffries in Reno, Nevada on July 4, 1910 in front of 20,000 people. After beating Jeffries, whites were so outraged they rioted in cities across the U.S., killing several African-Americans in the process.

Johnson never felt whites were superior to him

One reason many whites did not like Johnson at the time was became of his attitude. He was flamboyant, he regularly dated white woman, and he flaunted his wealth. He did not believe Black people were inferior to their white peers and did not stay in his “place.” As he once reportedly said, “As I grew up, the white boys were my friends and my pals. I ate with them, played with them and slept at their homes. Their mothers gave me cookies, and I ate at their tables. No one ever taught me that white men were superior to me.”

Johnson was convicted of the Mann Act in 1913

Because many whites hated Johnson’s brash personality and his relationships with white women, several officials looked for ways to derail his career. In 1913, he was convicted of the Mann Act, which accused the boxer of “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes.” He was sentenced to a year in prison, but Johnson fled the country before he could be incarcerated. He ended up in Europe where he continued to box to make ends meet, but eventually lost his championship title in Cuba in 1915. In 1920, Johnson returned to the States where he would serve his prison sentence.

A fan of fast cars, Johnson died in an automobile accident in 1946.