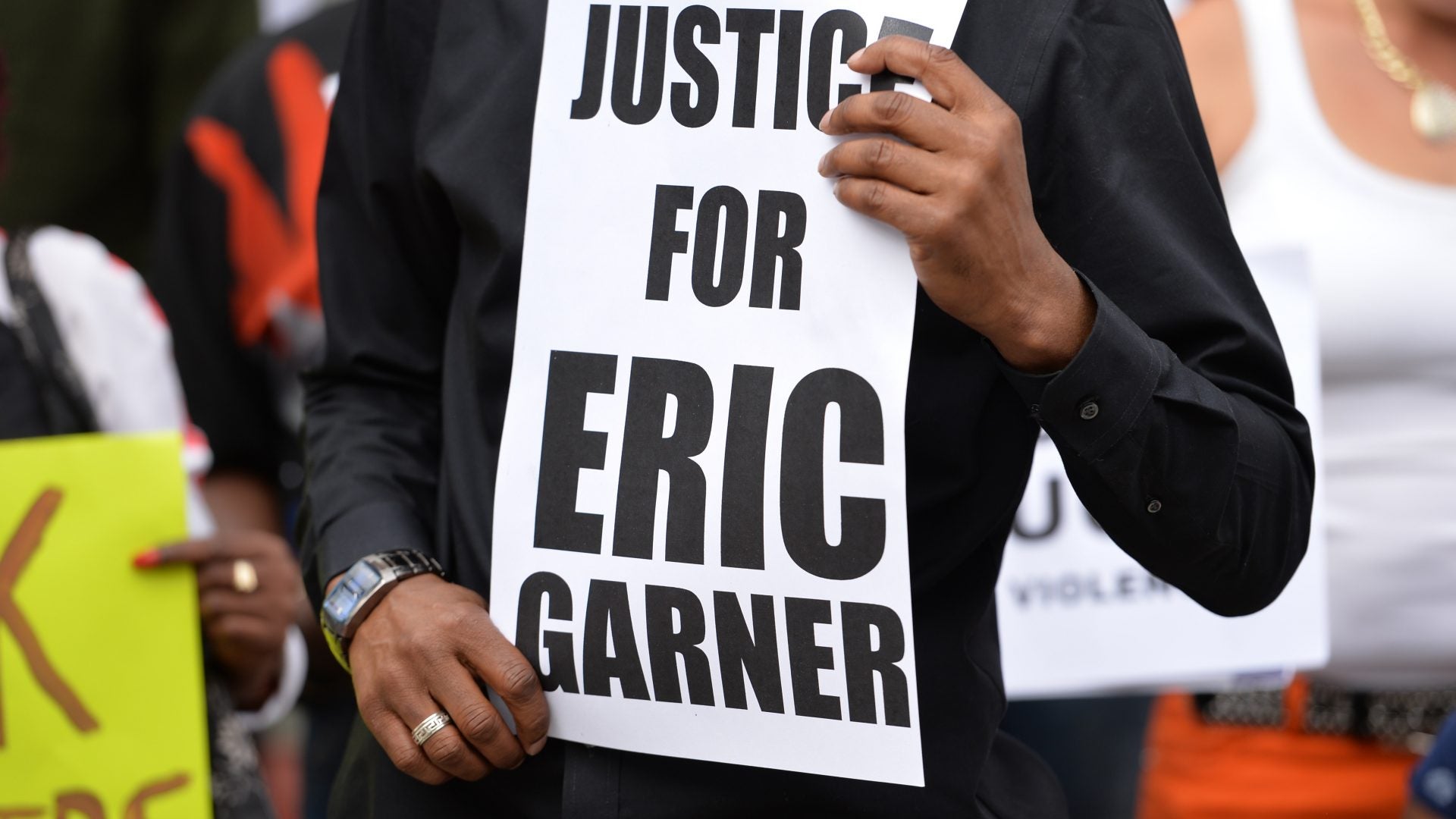

Ten years ago, a disturbing video emerged of Eric Garner struggling against an NYPD policeman’s chokehold. Garner’s last words, “I can’t breathe”, served as a searing symbol of the police brutality Black people are far too frequently subjected to. His death galvanized Black Lives Matter protests across the country and foreshadowed future protests as a chilling series of Black people continued to die at the hands of police.

18-year-old Mike Brown was shot to death by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014. Police in Cleveland, Ohio, gunned down 12-year-old Tamir Rice while he played with a toy gun in November 2014. 32-year-old Philando Castile was shot to death during a traffic stop in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in front of his girlfriend and her 4-year-old daughter in July 2016. Four years later, Minnesota was the site of another infamous instance of police brutality, when 46-year-old George Floyd gasped for breath for an excruciating 9 minutes and 29 seconds while policeman Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck. Like Garner, Floyd’s last words were, “I can’t breathe.”

The ensuing Black Lives Matter protests shook the nation and sparked a racial reckoning in which numerous sectors of society, from government to schools to policing, committed to racial equity. But in the ten years since Garner was killed, how much has really changed?

Garner’s mother, Gwen Carr, noted at a commemoration for her son held on Wednesday in Staten Island that police have been using body cameras more frequently, as reported by Time magazine. Few police were using them back in 2014, but since 2019, all NYPD officers who perform patrol duties must wear the cameras. The body camera program, which includes 24,000 officers, is now the largest of its kind in the United States.

NYC has also enacted a law that bans and criminalizes the use of chokeholds by police. The Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act was passed in 2020 after George Floyd’s death and was upheld by the state’s highest court last year. Ironically, the NYPD already had a chokehold ban dating back to 1993, but it didn’t apply if the officer’s life was in danger, which allowed its use to continue. In fact, in 2014, when NYC’s Civilian Complaint Review Board studied the use of chokeholds, they found that hundreds of complaints were made accusing the NYPD of using the technique.

A lack of accountability was a big part of the problem with the previous ban, according to Paul Butler, a former federal prosecutor and author of the book Chokehold: Policing Black Men. In an interview for NPR, Butler said, “If we look at the ban in New York City, it’s kind of like a rule in an employee handbook: ‘Don’t use a chokehold.’ We shouldn’t expect those kinds of light bans to work.”

The Eric Garner Anti-Chokehold Act, however, carries a sentence of up to 15 years for police officers found guilty of using a chokehold or otherwise hindering breathing by kneeling, standing, or sitting on someone’s torso. But loopholes remain, the police officer had to have employed the chokehold voluntarily, “not accidentally,” and “such conduct must fall outside the parameters of justifiable use of physical force,” as reported by the AP.

Garner’s mother thinks the law should be more far-reaching. In an interview with WABC 7, Carr said, “We need a nationwide law that says you cannot choke a person to death. You cannot obstruct their breathing.”

She also believes that qualified immunity, which shields police from liability for misconduct, even breaking the law, should be abolished. “If we could get rid of that qualified immunity, I think we would have a better police force,” Carr said in the same interview.

David Pantaleo, the officer who killed Garner, was fired from the NYPD in 2019 but never faced criminal charges, even though Garner’s death was ruled a homicide.

The Garner family sued the city and settled for $5.9 million but sought a legal inquiry into Garner’s death in 2021 to bring some modicum of justice to the case. The proceeding allows citizens to request a public inquiry for “any alleged violation or neglect of duty in relation to the property, government or affairs of the city.” The purpose of the inquiry wasn’t to establish guilt or innocence but to establish a record of the case, according to Time magazine.

Alvin Bragg, now Manhattan District Attorney, was one of the civil rights lawyers who represented the Garner family in that case. Bragg praised the family and their advocacy in a statement reported by Time. “While I am still deeply pained by the loss of Eric Garner, I am in awe of his family’s strength and moved by their commitment to use his legacy as a force for change,” He continued, “Their courage continues to inspire me as district attorney, and I pledge to always honor Mr. Garner’s memory by working towards a safer, fairer and more equal city.”