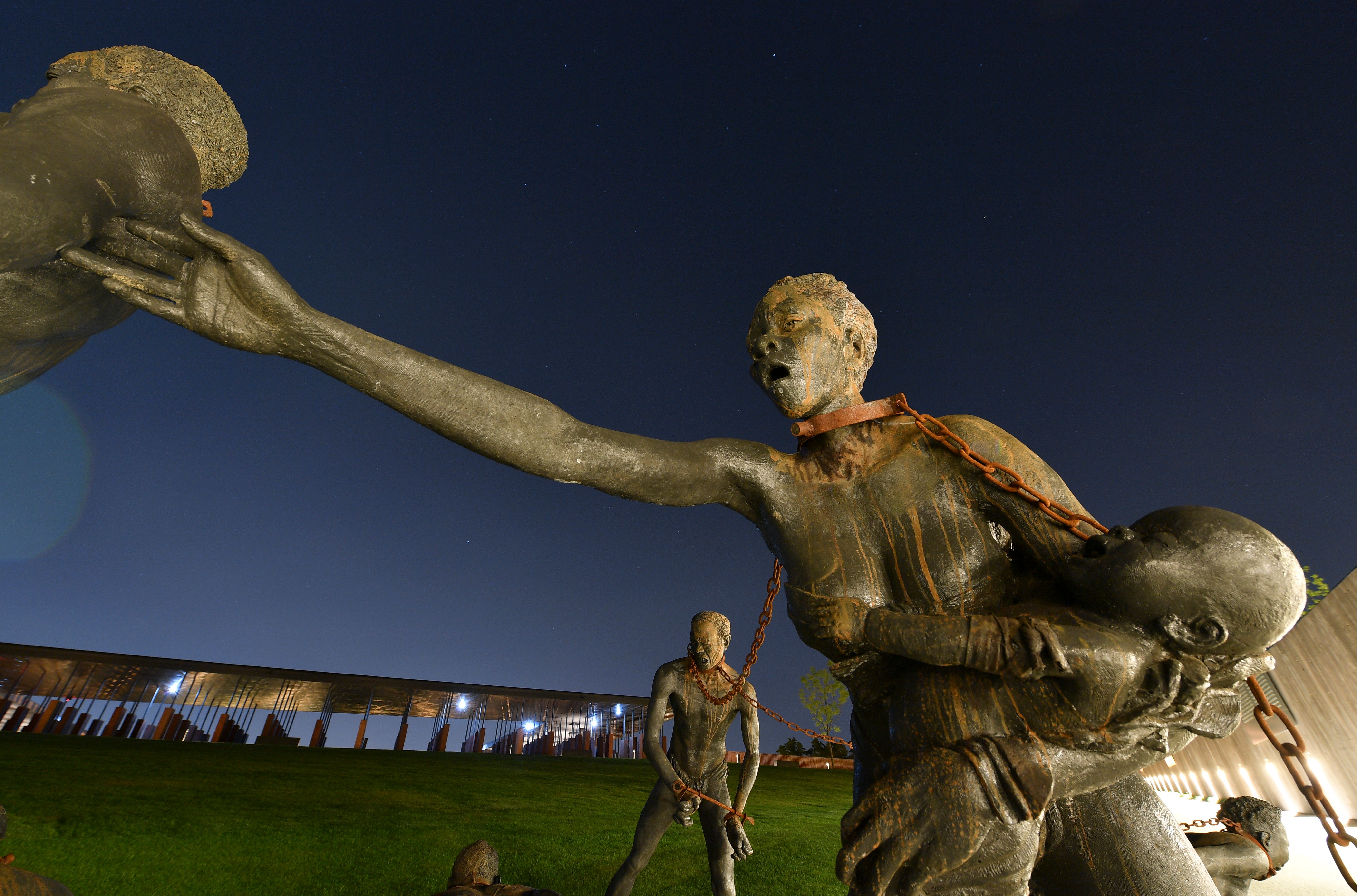

The nation’s first memorial to the victims of lynching opened last Thursday in Alabama, with many lauding it is a powerful symbol that acknowledges America’s shameful past.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice commemorates 4,400 African Americans who were killed in lynchings and other racism-related murders between 1877 and 1950. The known names of those slain are engraved on 800 columns that are dramatically suspended in the air. The columns represent each county where lynchings occurred, highlighting that these acts of terror were not limited to the South.

“Whites wouldn’t talk about it because of shame. Blacks wouldn’t talk about it because of fear,” Rev. Jesse Jackson said of how the memorial pushes back on the country’s silence on the subject of lynching.

“There are forces in America today trying to take us back,” Congressman John Lewis said, adding, “We’re not going back. We’re going forward with this museum.”

Despite the significance of the memorial, many in Alabama are not happy with it. Some insist that all it does is invoke a terrible past, The Guardian reports.

“It’s going to cause an uproar and open old wounds,” said Mikki Keenan, a 58-year-old Montgomery resident told The Guardian, adding that many felt that “it’s a waste of money, a waste of space and it’s bringing up bullshit”.

Jackson and Lewis attended the opening alongside other notables including filmmaker Ava DuVernay, playwright Anna Deavere Smith, and singer Patti Labelle among other artists, singers, and activists, according to the Denver Post.

Also in attendance were activists from the 1950s Montgomery bus boycott, Freedom Rider Bernard Lafayette, activist Gloria Steinem, one of the original Little Rock Nine Elizabeth Eckford, and activist Marian Wright Edelman.

A related museum called “The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration” is set to also open.

The memorial has been years in the making, a long-term project of the Montgomery-based legal advocacy group Equal Justice Initiative, founded by MacArthur genius attorney Bryan Stevenson.

“Enslaved people were promised freedom, and what they got was terrorism. During the era of lynching, black people were promised security, but what they got was humiliation and segregation,” Stevenson told Vox. “We were promised equality and voting rights in the 1960s, and what we got was mass incarceration and criminalization.”

Equal Justice Initiative, first created to fight for justice for people on death row, did six years of research and made extensive visits to southern sites to bring the memorial together.

“I think we have developed a really advanced coping mechanism of silence,” Stevenson told CNN. “I am hoping that people leave this space and say to themselves ‘never again.’”