On November 26 2023, artists representing the enormity of Atlanta hip-hop took over the field at Mercedes Benz Stadium to celebrate #ATL50HipHop just before an Atlanta Falcons game. For those of us old enough to remember when Atlanta began its fight to be respected in hip-hop music, the number of artists was a sight to behold. Just years after Colin Kaepernick was blacklisted from protesting police brutality, one wonders what the family of Deacon Johnny Hollman feels about the paradoxical celebration. They’d just spent Thanksgiving without him, a few days after Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis agreed to release bodycam footage of Atlanta Police killing their patriarch.

Does the south still have something to say when we have a “mayor named Dre?”

Since the 1995 Source Awards, many have taken Andre 3000’s iconic declaration that the “South got something to say” as a battle cry for those born and raised in ‘the dirty south.’ Andre “3000” Benjamin– indisputably one of the most talented lyricists to ever do it and one half of rap’s greatest duo, Outkast– stood on the Source Awards stage and stared down creatives who believed that only NYC and California could lay claim to hip-hop. Donning a purple and white dashiki, he accepted the sharp black lacquer trophy with defiance, affirming that the beats and bars rooted in African traditions that migrated from the South to other parts of the country mattered.

His crystal clear words, dripping with his southside-of-Atlanta drawl, resonated with us as southerners. Despite being mischaracterized as docile and slow, we know that our stories are the fertile ground from which so much culture– and resistance– in this country, flows.

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens launched ATL50 Hip Hop on August 1, 2023. Dickens declared, “Hip Hop goes beyond music—from…building economic empires or political movements, it resonates beyond sound.” A bit over a week later, on what was designated as “Dungeon Family Appreciation Day,” Atlanta Police officer Kiran Kimbrough killed 62-year-old deacon Johnny Hollman, Sr., who was on his way home to take his wife to dinner when he had a minor traffic accident.

After a disagreement about a citation, Kimbrough tased Hollman and allowed a civilian tow truck driver to kneel on his neck. During the encounter, which lasted over 17 minutes, Hollman uttered “I can’t breathe” at least 15 times.

News of the Hollman tragedy would not overtake local headlines like the Memphis police killing of Tyre Nichols. This is despite Atlanta’s contribution to the culture that led to Nichols’ death. Indeed, Memphis’ police chief once supervised the Atlanta Police REDDOG tactical unit.

Mayor Dickens, who did not respond to requests for comment for this story, posted a multi-part video to social media urging calm as the country braced for body camera footage. He released a statement, describing himself as experiencing “sickness and anger” after Nichols’ brutal killing.

DA Fani Willis released the video of Hollman’s death only after the family petitioned Dickens and the City Council for months. In curious contrast, Dickens’ statement reacting to the footage in his own city was less impassioned. He offered condolences about the killing itself, but offered no criticism of a policing system that has historically harmed Black men like Hollman.

Despite community support for the Hollmans, the creative sphere’s response has been more tepid than the mayor’s, with few artists publicly standing with the family to confront the State. It begs the question: Does the south still have something to say when we have a “mayor named Dre?”

The first time my mother heard me listening to G.O.O.D.I.E. M.O.B.’s “Dirty South,” she recoiled. “Tiffany, that’s not a nice phrase.” In her experience, those words were weaponized to smear not only a region, but southern Black people. She didn’t know that the opening line of the tune was storytelling about Atlanta, policing, the War on Drugs, and state violence:

“one to da two da three da fo’, them Dirty RED DOGS done hit the do’ and they got everybody on they hands and knees and they ain’t gon’ leave until they find them keys”

-Goodie Mob, “Dirty South”

With the question, “what you really know about the Dirty South?” Cee-lo, Khujo, T-Mo and Big Gip Goodie, joined by OutKast’s Big Boi, explained that Black folks in Atlanta and the rest of the south were caught in the crosshairs of law enforcement tactics rooted in chattel slavery. Instead of navigating concrete jungles, we were surviving political warfare in forests and fields with seemingly no one paying close attention.

Atlanta’s REDDOG unit was deadly as it is fabled. Known for throwing punches, pulling triggers and asking questions later, the mostly Black tactical unit was merciless. And many endorsed their carnage because of the nationwide hysteria around guns, drugs and “black-on-black crime.”

The Unit finally came into scrutiny after killing and later defaming 92-year-old Kathryn Johnston as she laid in her bed. Despite former Mayor Kasim Reed consequently caving to organized community pressure and disbanding the unit in 2011, REDDOG’s legacy endures. From OutKast to T.I., 2Chainz and Lil Baby, Atlanta rap lyrics detail the corruption and danger of local law enforcement:

“They trainin’ officers to kill us/ Then shootin’ protestors with these rubber bullets/ They regular people, I know that they feel it/ These scars too deep to heal us”

-Lil Baby, “Bigger Picture”, 2020

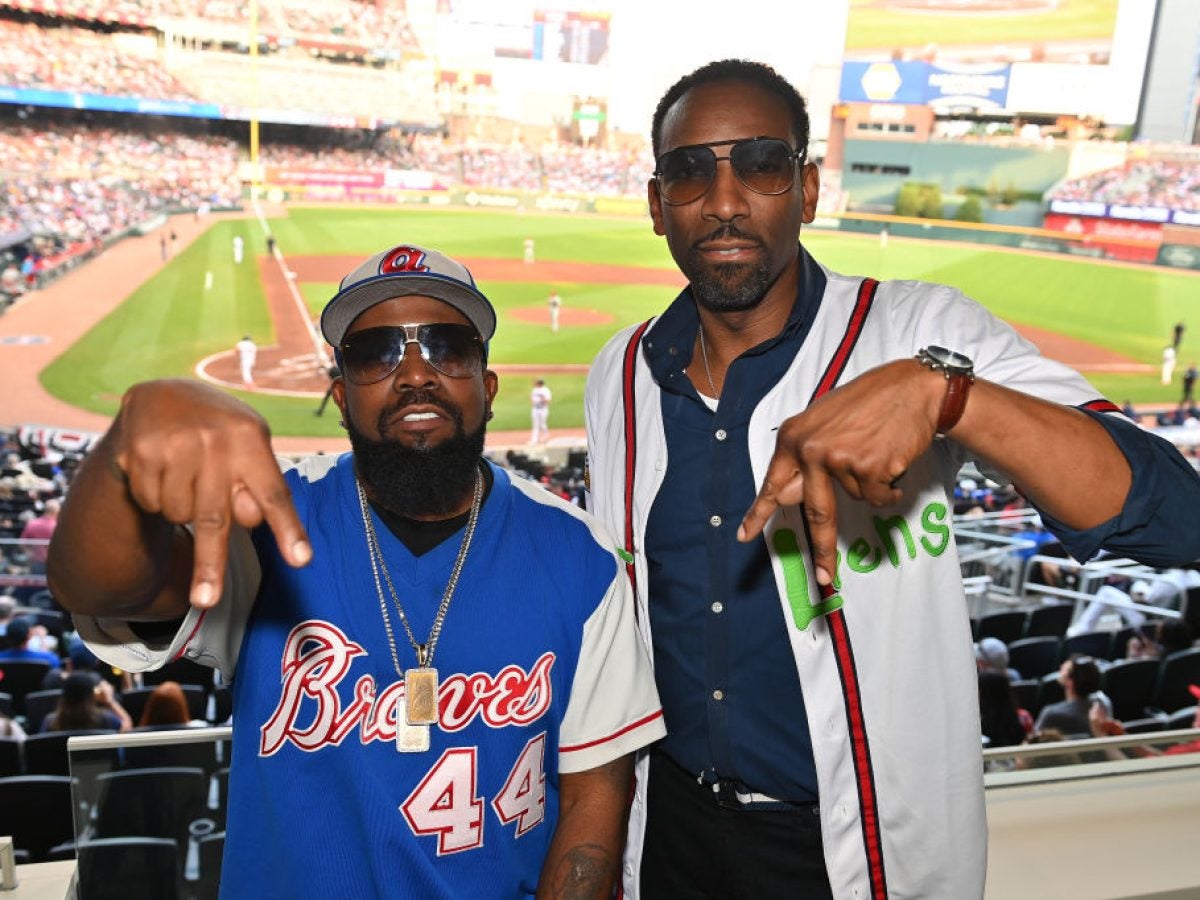

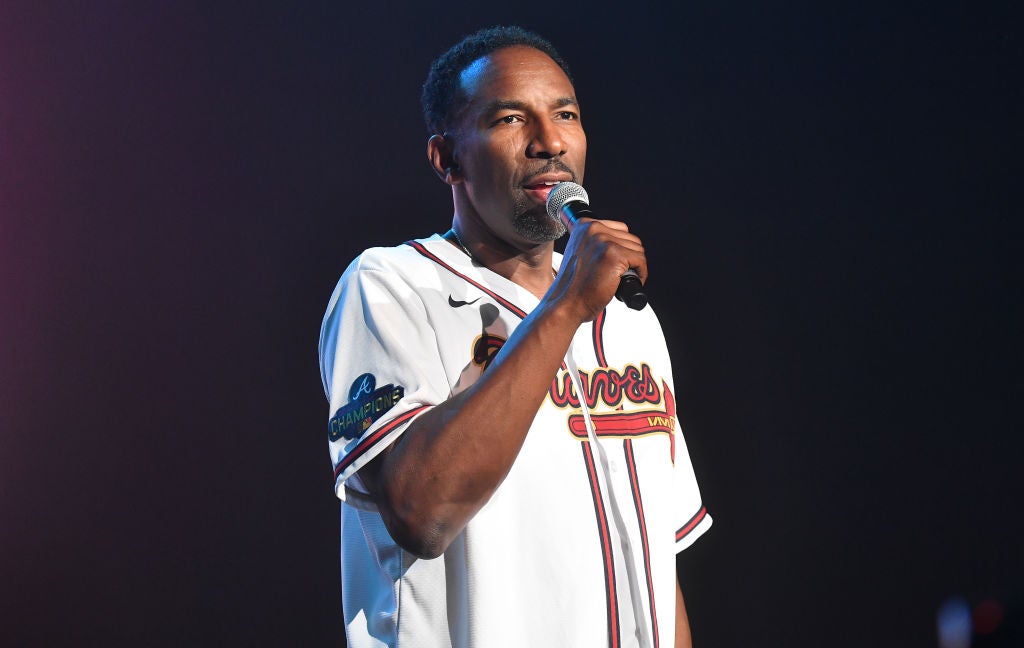

Atlanta artists have spoken publicly about social issues such as police violence, cash bail, voting rights and mass incarceration. But when 2020 marches morphed into uprisings, some of them joined politicians to publicly chastise people in the streets. Over the next few years, we saw more photographs of entertainers with officials than with the people.

Beyond charity and philanthropy, industry voices and material resources do not often flow to Atlanta organizations confronting critical issues. This reality may stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of how transformative power functions. Some mistakenly believe that change is accomplished from the top down; history teaches us it is quite the opposite.

Much of Atlanta’s creative community ironically greets the 50th birthday of what once was an outcast genre with a level of (perhaps unintentional) complicity in the assault on their Black consumers who dream of a better world.

The class solidarity between Atlanta’s political elite and entertainment industry exemplifies the danger of misappropriating Black culture to co-opt and chill Black political dissent. Atlanta is no longer “up-and-coming” and perhaps fewer artists identify with the have-nots. As the presence of our artists on the main stage has become the rule, rather than the exception, much of Atlanta’s creative community ironically greets the 50th birthday of what once was an outcast genre with a level of (perhaps unintentional) complicity in the assault on their Black consumers who dream of a better world.

“We on our back, starin’ at the stars above/ Talkin’ bout what we gonna be when we grow up/ I said, “What you wanna be?” She said, ‘Alive.’”

-Outkast, Da Art of Storytellin’

The ATL 50 Hip Hop series was so expensive that the city canceled its annual NYE Peach Drop festivities (though officials also say “additional local activities” also used up the budget). The superficial pageantry of Atlanta’s mayoral seat has overtaken the call to meaningfully engage constituents on tough issues.

Mayor Dickens and his supporters court artists and influencers while shunning organizers and advocates. By cowering just behind Atlanta’s veneer of upward mobility and celebrity, mayors like Dickens effectively eschew valid critiques of their criminal legal system tactics.

According to data scientist Samuel Sinyangwe’s Mapping Police Violence database, police killed more people in 2023 than any other year in recent history, despite so-called reforms. And 2023 was not only the 50th anniversary of hip-hop. It also marked the 50th anniversary of mass incarceration.

“But legislation got this new policy: three strikes and you’re ruined. Now where your crew at?”

-Outkast, “Slump”

The ironic convergence of these two milestones is no clearer than in Atlanta, where the city is on the world’s stage because of its government’s shameless assaults on human rights. With Dickens’ paralyzing fixation on law enforcement, the largest wealth gap in the country, 100% of unarmed people killed by police being Black and ranking as the most surveilled city in the nation, this is no Mecca for vulnerable people.

As artists reap the harvest of Atlanta’s vibrant culture, they have the opportunity to flank community organizations and condemn violent crusades waged on Black people in the name of policing. This call does not place the burden of liberation at entertainers’ feet. Rather, it situates them shoulder to shoulder with the communities who made their success possible. It reminds them in these dire times that families like Deacon Hollman’s make Atlanta, not politicians. In the words of Khujo Goodie in “Cell Therapy”: “Listen to me now. Believe me later on.”

Tiffany Roberts is an attorney-organizer in Atlanta, GA whose work focuses on community-based policy solutions to mass incarceration & state violence. She is currently Director of Public Policy at non-profit law firm Southern Center for Human Rights and Chair of the Social Justice Ministry at her church.