It had been eight years since Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat on the bus, sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the fight toward desegregation was stagnating. Civil rights leaders needed something that would reignite the cause and those committed, and they finally got one in the spring of 1963, “after an unorthodox plan to recruit Black children to march was implemented, the movement reversed itself, reinvigorating the fight for racial equality,” in what is now referred to as the Birmingham Children’s March.

Whose idea was it to involve children? James Bevel, a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, came up with the unique strategy, which “involved recruiting popular teenagers from Black high schools, such as the quarterbacks and cheerleaders, who could influence their classmates to attend meetings with them at Black churches in Birmingham to learn about the non-violent movement.” Another bonus of involving youth had to do with the economy—if adults participated in these marches, they were at risk of getting fired and losing gainful employment.

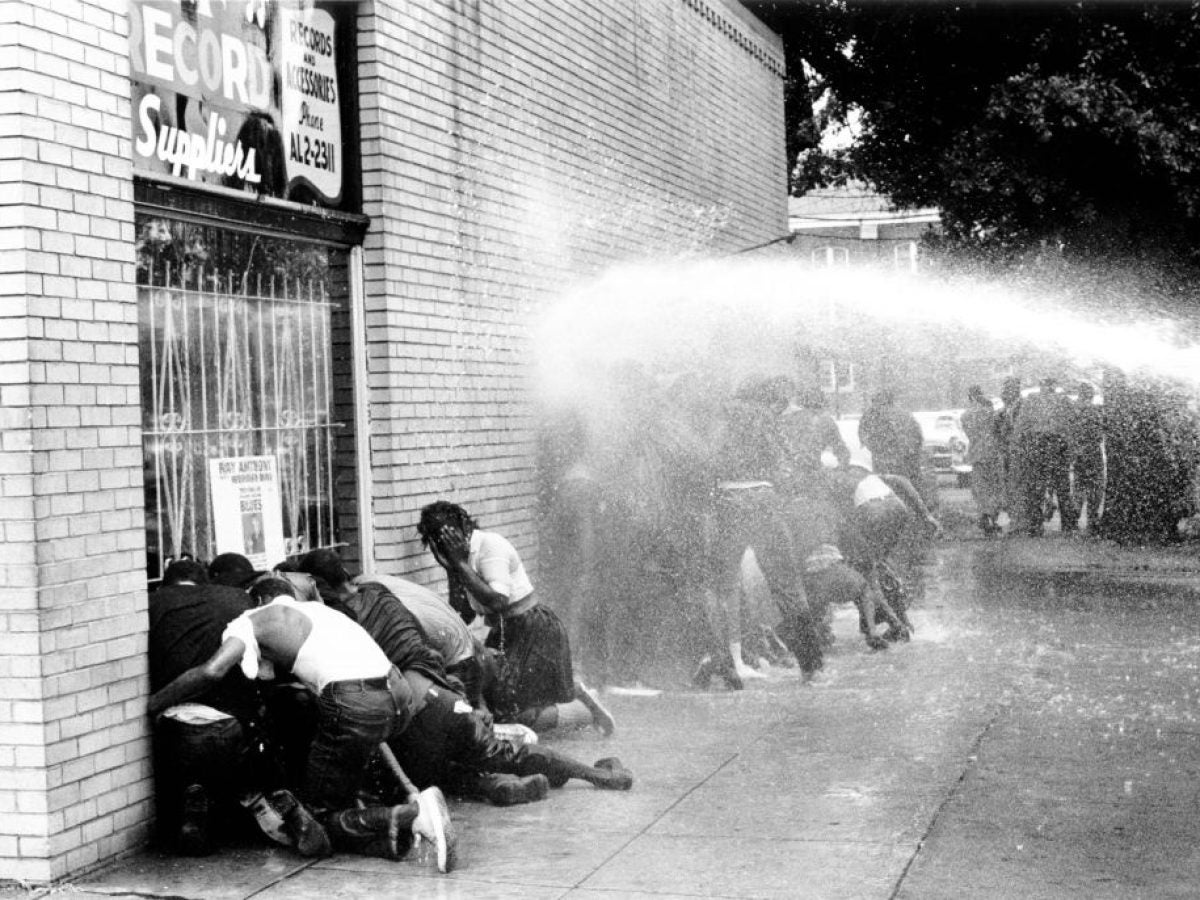

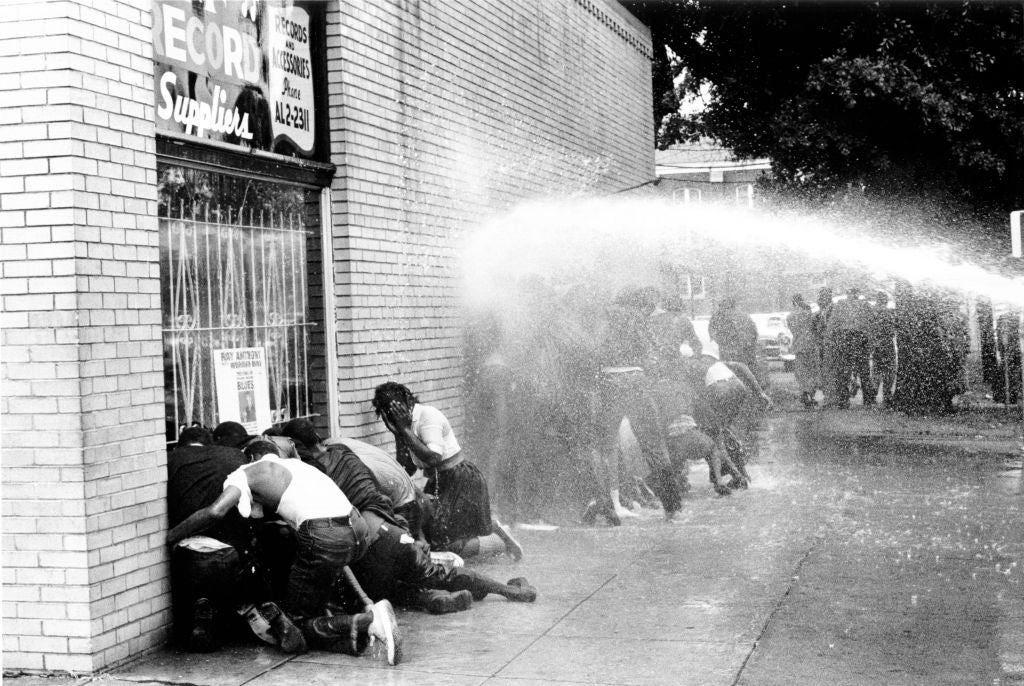

As a result of these circumstances, on May 3, 1963, hundreds of young people gathered in Birmingham as part of a 10-week protest against segregation. They would be attempting to march from the 16th Street Baptist Church down to City Hall, which is only a distance of 0.5 miles. But many never even made it through the full route because Eugene “Bull” Connor, the white Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety, “directed the local police and fire departments to use force to halt the demonstration.”

This might have been an invisible moment in history had photographers not captured the violence.

The images captured that day literally became the spark that reignited the flagging movement as photos “of children being blasted by high-pressure fire hoses, being clubbed by police officers, and being attacked by police dogs appeared on television and in newspapers, and triggered outrage throughout the world.”

In a serendipitous instance, esteemed civil rights photographer Hudson, captured the exact moment “when a police officer grabbed the fifteen-year-old Walter Gadsden by the collar, pulling the boy toward him to provide an easy target for the attack dog at his side. Gadsden looks on, powerless to repel the dog lunging for his abdomen.” The next day, Hudson’s iconic photo, which has become now synonymous with this march, ended up on the front of The New York Times.

As Atlanta’s High Museum notes, “Hudson often avoided hostility from the police by keeping his camera hidden under his jacket, only to be brought out at the optimal moment.”

As part of the same march, children are pictured assaulted by water canons.

Children seemed to have been the magic, humanizing elixir to galvanize the moment, because after this and other photos of children being attacked traveled around the world, “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., city official and President John Kennedy negotiated a truce.” A week later public facilities were being desegregated in Birmingham.

Indeed, as Vice writes, “If it wasn’t for the photograph of the clench-jawed cop straining at the leash of his German shepherd as it lunges into the belly of a black teenager, there would probably be no Civil Rights Act, no Voting Rights Act, nor any sort of equal rights act at all.”

While much about Gadsden’s life is still shrouded in mystery, you can go to a park located near the center of Birmingham and find this striking tableau “immortalized in bronze.”

This type of activism amongst young people is not uncommon and still persists today. Just this past March, “Black youth organizers were at the center of [a] rally that was organized by the Stop Cop City Coalition, In Defense of Black Lives (IDBL),” in the fight against the bulldozing of acres of forest and building a $90 million police center.

In Kansas City, the Black Youth Coalition Network is striving to create social and civic engagement through community service and activism, and in Delaware, Black high school students are organizing their second summit where all things leadership, activism, and organized will be discussed.

It is inspiring to think that these are only a couple examples out of many such instances occurring around the country, where Black youth are sustaining the frontlines, continuing the battle of their ancestors.