August is National Black Business Month, and ESSENCE is celebrating Black economic excellence and taking a look at the important history of Black cooperatives.

According to data from the last census, “there were 3.12 million Black-owned businesses in the United States, generating $206 billion in annual revenue and supporting 3.56 million U.S. jobs.” Inspiringly, “Black women are the fastest-growing group of entrepreneurs,” yet they receive less than 1% of funding from venture capitalists.

But “Black entrepreneurship is an important tool for closing the racial wealth gap, as it supports direct wealth creation, expands Black employment, and keeps local money circulating locally,” per a report from Brookings Institution. “Unfortunately, Black businesses have a higher failure rate than other businesses due to systemic barriers.”

One tool Black Americans have used to fight these systemic barriers has been cooperatives. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “A cooperative is defined as a user-owned and controlled business from which benefits are derived and distributed equitably on the basis of use or as a business owned and controlled by the people who use its services.”

One of the first examples of a Black cooperative can be traced back to “the early centuries in the US, [when] enslaved as well as free African Americans pooled their money to buy their own and their family members’ freedom.”

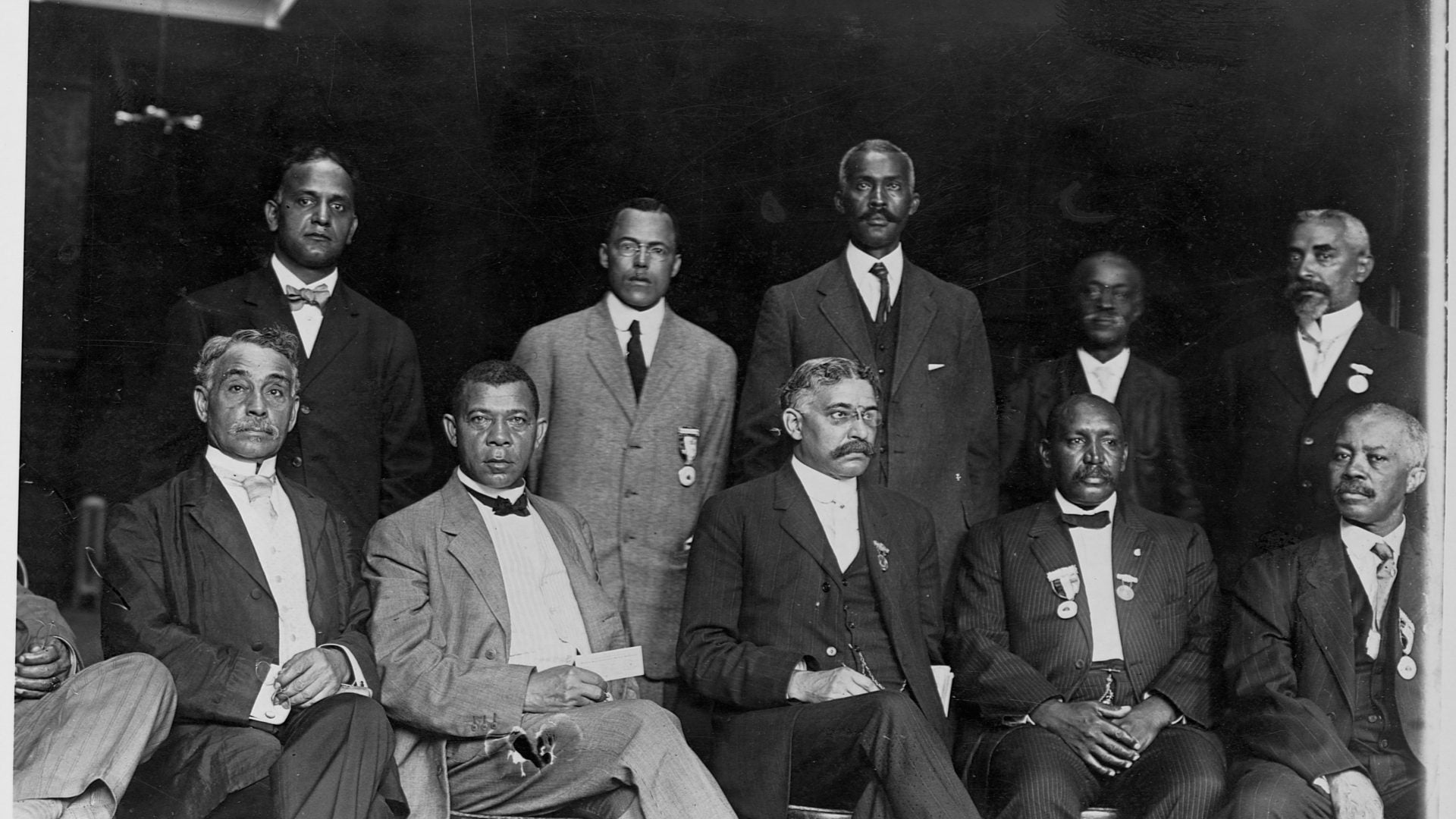

Many prominent Black historical icons “were also leaders in the Black cooperative movement – including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ella Jo Baker, A Philip Randolph, George Schuyler, Marcus Garvey (and his Universal Negro Improvement Association), Nannie Helen Burroughs, and the Black Panther Party, the Student National Coordinating Committee, and at times the Nation of Islam.”

Dr. Jessica Gordon Nembhard has conducted extensive research on this topic and published the book “Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice.” As Nembhard explained, “African Americans started using cooperative economics from the moment they were forcibly brought to the Americas from Africa, at first for practical reasons. They realized that their survival depended on working together and sharing resources.”

This tradition continued, and from cooperative stores and warehouses to credit outlets, cooperatives have been an important part of attempts for Black Americans to gain economic and political ground. In 1927, the National Negro Business League founded “the Colored Merchants Association, a marketing cooperative of independent African American grocers.” The Freedom Quilting Bee was a cooperative founded by sharecropping women in 1967—a year after being established, “the cooperative bought twenty-three acres of land on which to build their sewing factory. They also provided day care and after-school services for members’ children and others at the sewing factory.”

After the Rodney King riots, Food from the ‘Hood emerged as a student-led co-op at Crenshaw High School in 1992. This cooperative “started a school garden and gave the produce to their low-income neighbors. They also began to sell their vegetables at a farmers’ market, and then started a multiyear project to sell salad dressing made from produce grown in their school garden.”

In recent years, Black business cooperatives have been utilized by Black farmers as an avenue “to address food insecurity and establish food sovereignty within their communities.”

Black Urban Gardeners and Farmers of Pittsburgh Co-op (BUGS) founder Raqueeb Bey started her cooperative because it was “impractical to wait for the system to adjust to meet the needs of the Black community.”

Even though Black people in this country have long been denied the same rights as their white counterparts, Black business cooperatives have long been and continue to be not only a form of resistance but a tool where members can utilize their services, assisting in the creation of wealth and gaining economic independent for and within the Black community.