In July, New York and California passed the CROWN (Creating a Respectful and Open Workplace) Act, marking the first time in U.S. history that discrimination against natural hair and natural hairstyles will be banned. More specifically, the law covers traits historically associated with ethnicity.

In this case, they include hair textures and protective styles for which Black women are known. Such legislation has been a long time coming, at least according to Democratic State Senator Holly J. Mitchell, who spearheaded the bill in California. “For me it was, quite frankly, a perfect storm of issues and observations leading to opportunity,” Mitchell says.

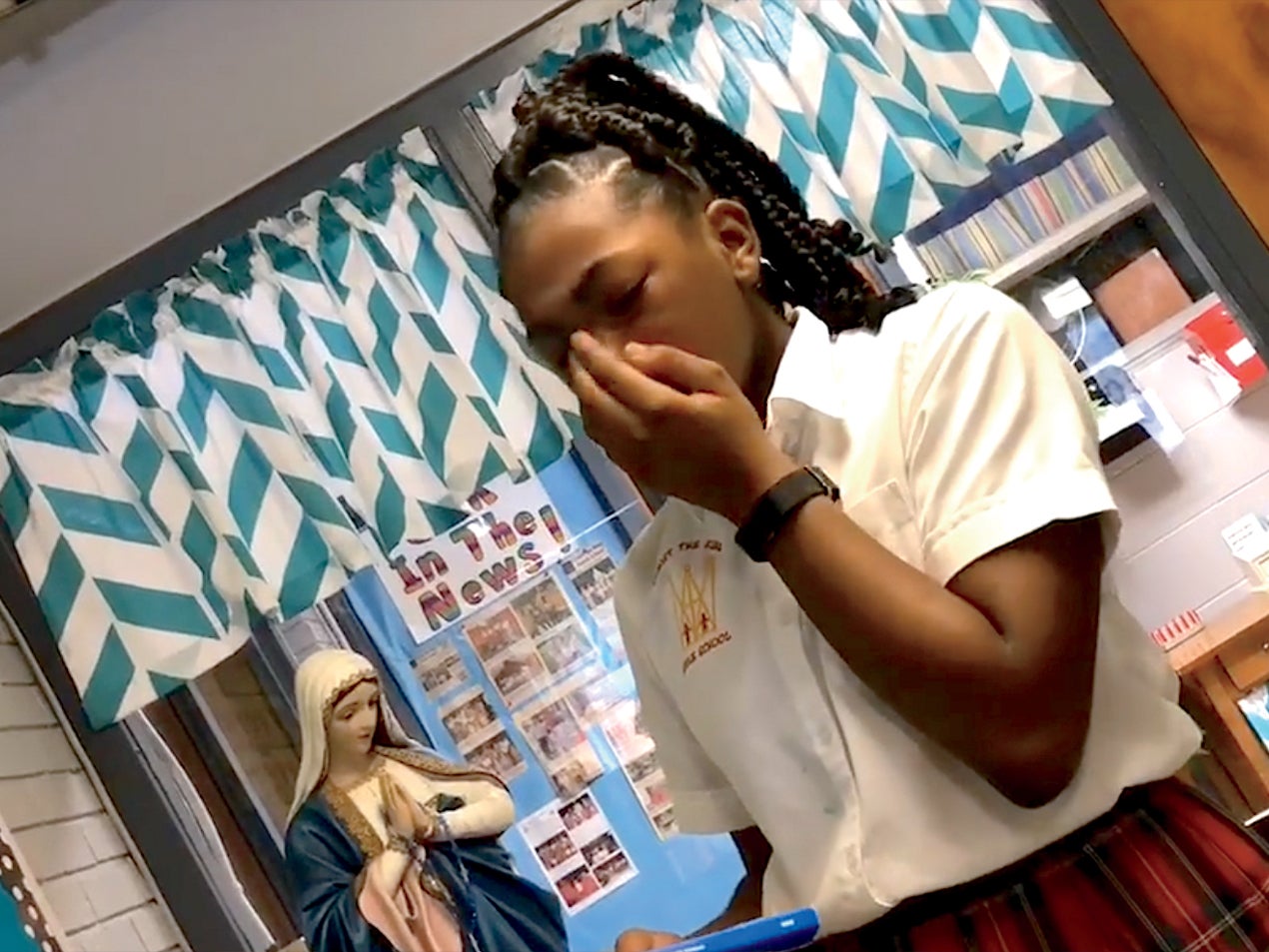

Before the CROWN Act, bias based on how Black people chose to wear their hair regularly lit up the news cycle, particularly in recent years, with the resurgence of locs and braided extensions. In August 2018, Faith Fennidy, 11, was sent home from her Catholic school in Terrytown, Louisiana, because of her thick braided extensions.

Meanwhile, in Fort Worth, Texas, 17-year-old Kerion Washington was denied a job at Six Flags because of his “extreme” locs. This act echoed a 2010 incident in which Chastity Jones wasn’t hired at an insurance company in Mobile, Alabama, because of her short natural locs.

The examples, unfortunately, are virtually endless. “I, and we collectively, stand on their shoulders,” Mitchell says of those who bore the weight of these incidents without legal recourse. Their experience was largely due to a court system that didn’t safeguard their individual rights and, she adds, “a body of law that didn’t include racial traits as a protected class.” All the other protected categories—age, gender, sexual orientation, religion—came as a result of the pain and suffering of our foremothers, Mitchell adds.

“They were the wind that gave us the opportunity to help challenge public perception, to help us push back on employer perception, to change the law.”

A CASE FOR CHANGE

When it comes to the hair category, one such catalyst has been Brittany Noble Jones, a Black journalist at WJTV in Jackson, Mississippi. In 2018 she began facing issues at work because of her natural do. “I wanted to stop straightening my hair because it was in really bad condition, especially after my son was born,” she recalls. “It was just too much. I’m a new mom. I’m dealing with the stress at home, I’m dealing with the stress in the newsroom of trying to pick stories, and I’m dealing with the stress of getting up super early in the morning.”

According to Jones, when she asked her boss if she could stop straightening her strands, he said yes. However, a month later he allegedly claimed that her natural locks were a problem. “Everybody makes it to be a big deal about my hair, and they overlook the fact that it was kind of my…protest for the stories that we were not being able to tell. We were not telling stories that I felt like we should have been, from a Black perspective.

And at some point I needed my boss to see that I reflected the people in our community that we’re not talking about. That was important for me,” she says. Jones, who lodged a formal complaint, notes that issues had come up before concerning her hair, but WJTV-TV and its parent company, Nexstar Media Group, have refuted her claims. “Allegations that Ms. Jones’s employment was terminated for any reason other than excessive absenteeism have no basis in fact and are vigorously denied.

Ms. Jones’s employment was terminated for excessive absenteeism when she failed to return to work and fulfill her contractual responsibilities after exhausting all available leave time,” noted Nexstar Media Group in a statement provided to ESSENCE. Eventually the situation became so frustrating that Jones went to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). At first it declined to take her case, claiming that it wasn’t strong enough.

The situation came to a head when Jones allegedly refused to wear a wig and instead went on TV with her natural tresses. According to her, the very next day she started getting performance reviews and critiques about “crazy stuff.” “I knew that nobody else was getting any kind of performance reviews,” she says. “So I’m like, How do you pick right now, today, to give me my first performance review? The day after I just decided not to wear a wig?”

She went back to the EEOC with this particular complaint, and that gave the agency the evidence it needed to define her case as being racially biased. The EEOC declined to comment on Jones’s case, with spokesperson Christine Saah Nazer citing federal law prohibiting the agency from commenting on or even confirming or denying the existence of possible charges.

“If it was not for me changing my hair one day on the desk and [the station] giving me the performance reviews, they wouldn’t have taken my case. They wouldn’t have taken it,” Jones says of the EEOC.

ADVOCACY FROM MORE AGENCIES

Other groups have also joined the fight. In February the New York City Commission on Human Rights issued guidelines making it illegal to discriminate against or target individuals over their hair, whether at work or school or in public spaces. The passage of the CROWN Act was, of course, a major victory for the commission. And then there is Unilever’s Dove, which co-founded the CROWN Coalition along with several other activist and advocacy groups to push for CROWN acts across the United States.

“If you think about hair, the fact that it is actually legal to tell someone they have to get rid of their braids or their locs to be given a job just doesn’t make sense,” Esi Eggleston Bracey, Unilever North America chief operating officer and executive vice-president of beauty and personal care, says. “The CROWN Coalition was really about finding like-minded partners that can help us make a real change, first in legislation, so that discrimination is no longer legal.

Our foremothers were the wind that gave us the opportunity to…push back on employer perception, to change the law.”

—HOLLY J. MITCHELL

We had to make sure that we can have the freedom and the right to wear our hair in braids or locs or any way that we choose our textured hair to be in the workplace and in schools.” Choice is the crux of the matter, namely the option for us to present our best, most authentic selves to the rest of the world as we see fit. “At some point all of us wear our hair natural,” says Mitchell.

“There is not a sister I know who doesn’t do summer vacation in the Caribbean or a family reunion in Alabama in July without her hair braided. When I went to the 2019 Essence Festival, it became kind of a joke that I could count the number of Black women I saw of the estimated 500,000 in attendance who did not have her hair in a protective style.

So I think every Black woman has had the experience of wearing her hair natural. The point of this legislation is to empower her to make that choice again based on her personal desires, not based on a concern about external perception about her professionalism.”

OTHER STATES FOLLOW SUIT

It is perhaps bittersweet that legislation has to be passed to protect our tresses and our culture in the first place, but true change, as Unilever’s Bracey points out, has seldom come about without the laws to enforce it. So far the response to the bills in New York and California has been overwhelmingly positive.

Shortly after those states announced the passage of the CROWN Act, New Jersey came out with its own version of the law, sponsored by Assemblywoman Angela McKnight of Jersey City, New Jersey. The Democrat, who wears her strands in a natural style, says she was deeply affected by the Andrew Johnson case: A wrestler at Buena Regional High School in Buena, New Jersey, Johnson had his locs hacked off in front of spectators before he was allowed to continue a match.

The incident made national headlines and sparked hurt and outrage. “I introduced the hair discrimination bill because of him,” she says, noting that she only became aware of the CROWN acts in the interim. “Whether or not they were happening, I was going to fight for Andrew Johnson.

But with the CROWN Act, it’s more leverage that this issue needs to change in the state. In our country it needs to change. “So the CROWN Act is passed. It’s out there and I’m happy, and I will use that to move forward in New Jersey, along with the Andrew Johnson story, and make sure that women of color… and men of color can wear their hair the way it’s naturally grown on their head,” McKnight adds.

We had to make sure that we can have the freedom and the right to wear our hair in braids or locs or any way that we choose.

—ESI EGGLESTON BRACEY

The momentum has picked up across the nation: Tennessee, Michigan, and Wisconsin are introducing similar legislation. The next goal is to have a bill in each and every state and, of course, federal legislation.

“This bill is a movement to protect Black citizens from systemic discrimination because of their hairstyles,” McKnight said. “I want this bill to uplift our people from being historically marginalized based on their identity. I want this bill to signify that change can happen, and it will happen, and because of this bill it has happened.”

She adds, “And I want people to know that they should continue to embrace who they are and love themselves for who they are. Especially their hair, because it’s part of their identity.”

Indeed change is coming: New York’s legislation became effective immediately, while California’s law will take effect on January 1, 2020. “The CROWN Act will make a huge difference for our future generations, who will grow up in a world that respects them,” Bracey reflects.

“Imagine a world in which our kids with natural hair don’t have to wonder, What am I going to do with my hair so that I can be accepted in the classroom or in a corporate environment? That should never be a concern for our children. And with this kind of legislation, we have the potential to ensure that.”

******

This article originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of ESSENCE Magazine, on newsstands now.