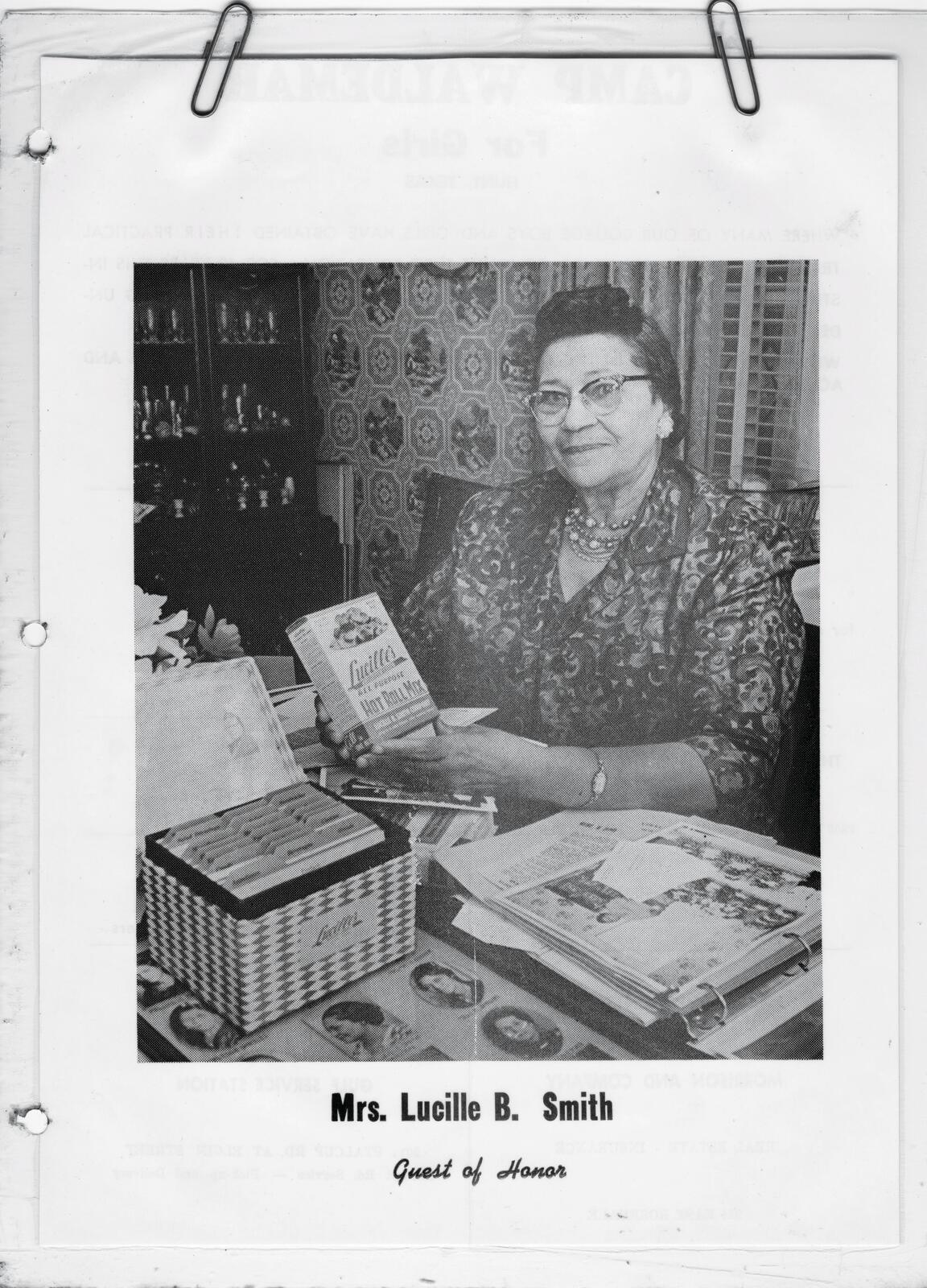

Chef Christopher Williams has been forging his own path for much of his culinary career. Trying his best not to look at what others are doing, he leans instead into his unique journey and builds on the decisions made by those who came before him. His restaurant, Lucille’s, which he co-founded with his brother Ben, is an ode to their great-grandmother, Lucille B. Smith, an educator, and entrepreneur whose recipes are the blueprint for much of the eatery’s success. It’s a point he stresses when told that he’s part of a group of young Black chefs helping to redefine the boundaries of African-American cuisine.

“I think we’re changing the conversation,” the James Beard Award–nominated chef says after a thoughtful pause. “As far as defining or redefining the cuisine, Lucille did that. She produced a cookbook with almost 425 recipes, covering everything from high French to Tex-Mex. She was in tune with not only technique but also indigenous ingredients and the flavor of our community. She’s done the work. What we are doing now is forcing the acknowledgment.”

Running a thriving enterprise like Lucille’s has been one of the first steps in forcing that acknowledgment—and gaining praise for dishes like Oxtail Tamales, Shrimp & Grits, Truffled Brussels Sprouts, and Grilled Octopus in Coconut Curry is another. The magnitude and diversity of his great-grandmother’s culinary knowledge have guided Williams toward showcasing his food without any limitations. Trained at Austin’s former Le Cordon Blue, Williams went on to study southern, French, Mediterranean, West Indian, and East African cuisine, all while traveling through Europe and the United States. He now wants to take even more steps to spotlight the influence of Black chefs like Smith who came before him, starting with announcing his first cookbook, a collaborative project with fellow Houstonian Kayla Stewart.

The two met when Stewart wrote a story on Lucille’s for the Southern Foodways Alliance. “We are from the same part of town,” says Williams of Stewart. “She is just a brilliant, brilliant writer. She came to do a piece on the restaurant, and we didn’t spend much time together, but she produced an incredible piece. It truly captured the intent of what we are doing here and the importance and impact of my great-grandmother’s legacy. After the article came out and we had a chance to reconnect, I had to give her flowers. We started talking and realized we wanted to do many similar things. I have always wanted to do an informative book to help deepen people’s experiences with food and different cuisines abroad, and I thought, This is the person to do it with.”

“As far as defining or redefining the cuisine, Lucille did that. She produced a cookbook with almost 425 recipes, covering everything from high French to Tex-Mex. She’s done the work. What we are doing now is forcing the acknowledgment.”

Traveling globally opened Williams’s eyes to the world’s view of American chefs and, by juxtaposition, African-American chefs. People he encountered didn’t have the highest opinion of the food coming from the States. Still, he was not pigeonholed into what people thought an African-American chef would create. “Nobody ever approached me about a sweet potato, cabbage, yams, or chitlins,” he says. The freedom allowed him to explore the palates of other cultures while increasing his admiration for his own.

“Our cuisine is American food,” he says. “How do you define jazz and blues? These inventions came from ingredients that were already here. We picked them up and added our flavor.”

Whether it’s music or food, this country’s only truly American art came through us.”

Williams plans to show people how expansive the box is with a cookbook highlighting African-American contributions to cuisine in the Lone Star State. The book, tentatively titled Black Texas, to be published by Ten Speed Press, will continue shining a spotlight on Smith’s legacy and illuminating the history of African-American cooking in Texas. While the food, such as barbecue and soul food, has inspired generations of chefs and fans, Williams wants to demonstrate that the influence is much more extensive, varied, and profound.

Written works like Bound to the Fire: How Virginia’s Enslaved Cooks Helped Invent American Cuisine, by Kelley Fanto Deetz; The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South, by Michael W. Twitty; A Letter to the Black Chef, Past, Present, and Future, Is There Hope? by Kevin Mitchell and more helped reveal the pivotal role that African-American chefs have played with American cuisine. This history has often been overshadowed or overlooked due to the progression of this country.

As is the case with many inventions by Black folks, the substance is celebrated while the creator is ignored. This leads to the real history behind fantastic creations eventually being lost—as though they appeared out of thin air. Only when people begin taking a deep dive into the past can we truly recognize and honor the contributions of those who laid the foundation. That recognition reveals that African-American food is the basis for American food. Whether it is barbecue, seafood, soul food, or another type, if the food has roots in the United States, it passed through and was shaped by Black hands.

“The only true American art forms in this country that survived are the ones that came through us,” Williams says. “Truly American cuisine is Black cuisine. I want to build past the narrative that our food is only soul food, barbecue, or breakfast. My great-grandmother is a self-published author who created a cookbook back in 1941. She wrote the recipes by hand, and her daughter, my grandmother, typed them. All we are doing is honoring their work and doing a bit of modernizing to bring those dishes back to life. We know the food works because some of the restaurant’s best-selling items come from her 100-year-old recipes. I wouldn’t even imagine messing with these dishes because they work as well today as they did a century ago.”

As Williams and Stewart move forward with Black Texas, they hope to create more connections to the past—while continuing to strengthen the foundation left by Smith.