If you ever find yourself, somewhere lost and surrounded by enemies who won’t let you speak in your own language who destroy your statues & instruments, who ban your omm bomm ba boom then you are in trouble deep trouble they ban your own boom ba boom you in deep deep trouble humph! probably take you several hundred years to get out! — Amiri Baraka, ‘Wise I’

The Clotilda, the last ship known to have smuggled enslaved Africans into the United States—decades after slavery was allegedly abolished—has been discovered in Alabama at the bottom of the Mobile River, the BBC reports.

It began with a bet, according to National Geographic, which reported that Timothy Meaher, “a wealthy landowner and shipbuilder from Mobile is said to have made a bet with northern businessmen that he could smuggle a cargo of African slaves into Mobile Bay under the nose of federal officials.”

The bet was for $1000.

“This new discovery brings the tragedy of slavery into focus while witnessing the triumph and resilience of the human spirit in overcoming the horrific crime that led to the establishment of Africatown,”

Lisa Demetropoulos Jones, executive director of AHC, said. After the Civil War, the Africans smuggled into the U.S on the Clotilda wanted to go back to Benin, but couldn’t afford the trip. Instead, they purchased small plots of land and formed their own tight-knit community in Alabama and named it Africatown.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IG6u1Rt8MaE

Today, Africatown is a working-class community of about 2,000 people north of downtown Mobile, where, for decades, the community spoke their native language. Environmental racism and lack of employment opportunities plague the community, but they keep going; they keep fighting. They remain the keepers of their own stories, because we, as Black people living in America, were robbed of our villages, our languages, and our histories.

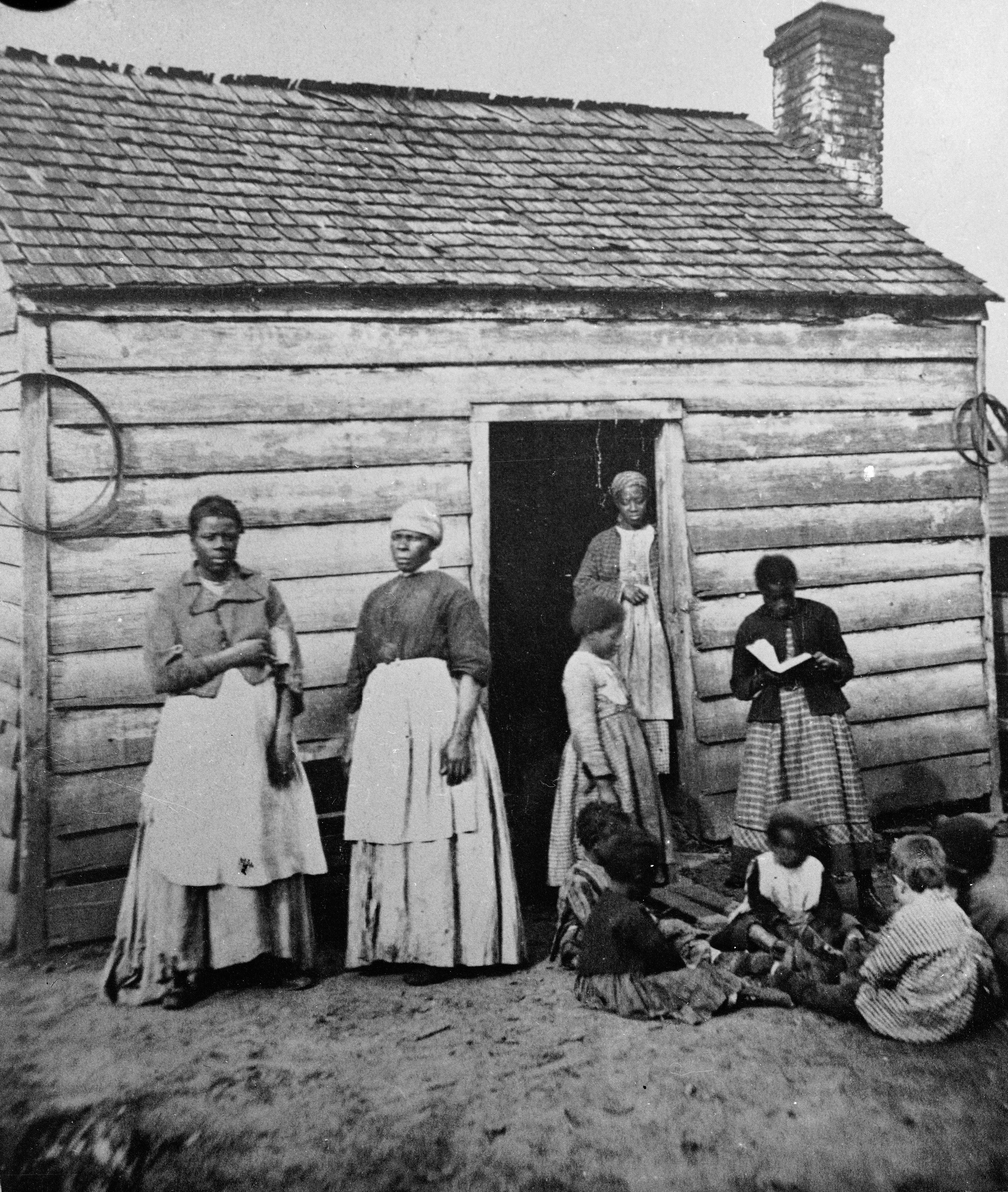

Too many of us can’t trace our ancestry beyond a grandparent or great-grandparent, because our ancestors were not only enslaved but told that reading and writing were punishable by death.

So, Africatown’s griots told their children about the Clotilda and the brutal violence and dehumanization their mothers and fathers faced; and their children told their children. This is what Black people have always done to keep our histories alive in a nation that tries to whitewash the Black blood on its hands and in every corner of its institutions.

Woods’ great-great-grandfather Charlie Lewis was the oldest of the enslaved Africans on board the ship, but naysayers had always been quick to dismiss the story as nothing but family lore. “This is the proof that we needed,” she said. “I am elated because so many people said that it didn’t really happen that way, that we made the story up.”

The 2018 discovery proved not to be the Clotilda, but Raines, archaeologists, and historians persevered. Now, Jones says that the discovered wreckage provides “tangible evidence of slavery.”

While I can appreciate the historical implications of unburying this floating torture chamber—and understand what it must mean to the descendants of the enslaved Africans shackled and forced to board the Clotilda, Black people don’t need any more “tangible evidence” of slavery.

Our very existence in this white supremacist capitalist nation is tangible evidence. Slavery shape-shifting into Jim Crow, mass criminalization and incarceration, employment and education discrimination, is tangible evidence. Modern police departments operating as “slave patrols” and committing state-sanctioned murder in occupied Black communities is tangible evidence. Alabama’s investment in the Prison Industrial Complex—coupled with draconian anti-abortion laws that disproportionately impact Black women whose foremothers were raped to maintain slavery—is tangible evidence.

Finding a ship in the depths of the Mobile River does not erase the fact that this nation has lied about the depths of its character since its inception. While the discovery of the Clotilda is powerful—and the feelings of connectedness and closure, no matter how painful, must be incredible—the people of Africatown deserve more than soliloquies about slavery; they deserve reparations.

Oluale Kossola, renamed Cudjo Lewis (or Cudjoe Lewis), in the United States, was one of the last living Clotilda survivors and pioneers of Africatown. Last month, U.K. researcher Hannah Durkin discovered that Redoshi, renamed Sally Smith in the U.S., had been the oldest living Clotilda survivor, outliving Kossola by two years.

In 1927, at the age of 86, he shared his lived experiences with author, journalist, playwright, and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston. Her book, Barracoon, published posthumously in 2018, includes his story.

Oluale Kossola, who was a member of the Tarkbar tribe, died in 1935.

His bones are buried in Africatown.