Crystal Brown-Tatum, 39, of Blanchard, Louisiana, was terrified when she was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer in 2007. “I knew that chemo would be the next step, but I was too scared to do it,” she says. “I envisioned myself frail, bald and throwing up all the time.”

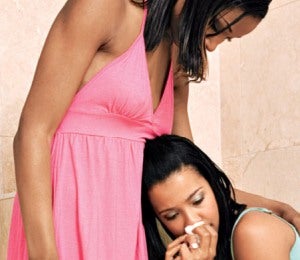

Feeling low, Brown-Tatum called her friend Tarsha, and they talked for three hours. Tarsha encouraged her to “fully embrace the experience” and eventually talked her into undergoing treatment. “Her support gave me the courage to do chemo — and most likely saved my life,” says Brown-Tatum, who is cancer-free today.

We all know it: Friends matter. And when we’re scared, in pain, sad or ill, that goes double. Trouble is, we don’t always know the right way to help. We might think we’re building a friend up after a miscarriage when we say, “You can always try again.” But those very words could make her feel her pain isn’t legitimate. And many of us are so uncomfortable with another’s suffering, so afraid of doing or saying the wrong thing, that we shy away. But that, experts say, is the worst lapse of all. “Avoiding a friend who’s sick or grieving can damage the friendship, sometimes beyond repair,” says Joyce Morley, Ed.D., a psychotherapist and relationship expert in Decatur, Georgia. Here’s how to be the kind of friend you’d want by your side in a critical situation.

A Sudden Health Crisis? Show Up

When Erin Calvin Thomas, 35, of Little Rock, Arkansas, had a stroke five years ago, her friend Katina left work to come to the hospital — and stayed for the better part of the week. “My other girlfriend, Brandy, brought me magazines to read, and my mom brought me gorgeous pajamas and fancy lotions for my hands and feet. I felt very loved and cared for,” says Thomas.

Thomas’ friends and family did the single most important thing: They showed up. “Just being there shows you care,” says Lori Hope, a cancer survivor and author of Help Me Live: 20 Things People With Cancer Want You to Know. Showing up can be as simple as driving a friend to a biopsy or sitting with her after surgery. “Being thoughtful lets her know she’s a priority in your life.” Ask her how she feels. Or try to imagine. Is it fear? Anger? Sadness? But don’t presume anything. “Listen to her without judging or offering advice,” says Hope. “Give her permission to feel however she’s feeling, and support her by saying things like, ‘That must be so hard.'”

Comments like that are more helpful than they sound, says Maxine Simpson, 42, of Raleigh, North Carolina, who was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma several years ago. Despite the treatments, “I know my life expectancy might be shorter because of the illness, and it’s scary,” she says. “Sometimes I just need friends to listen and empathize.”

A Chronic Illness? Stay in Touch

Nearly seven years ago, Tocombamaria K. Murphy, 37, of Shaker Heights, Ohio, was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, a chronic inflammatory bowel disease. “The initial fear subsides and you learn to live with it, but it’s not easy,” she reflects. “My friends check in, and if they think I sound tired they’ll say, ‘Are you having a flare-up?’ or ‘Would you like me to bring you dinner?’ Those kinds of questions let me know I’m not alone.”

Studies show people with long-term illnesses like diabetes are at increased risk of depression. It’s likely because they feel out of step with the world — more tired, more restricted in their activities. That’s why it’s especially important to stay in touch. Call frequently or have a weekly date to see a movie or go for a walk. But beware: Supporting someone with a chronic illness can wear on you too. “It can be tough to be super supportive over the long haul,” notes Hope. “And if your loved one senses she’s a burden, she may feel bad.” If you feel your compassion wearing thin, minimize telephone or face-to-face contact for a while, and replace it with sending cards or e-mails. You might also clip and send newspaper stories on new studies related to their illness or organizations that can help. “What’s most important is that she knows you love her and really do care,” says Hope.

Loss and Grief? Let Her Talk

When Nicole Barnes’s father passed away in 1999, she flew from her home in Michigan to Alabama, where her dad lived and stayed with her grandparents. A day after she arrived, her grandma’s doorbell rang and standing on the threshold was Yolanda, an old friend of Barnes’s from high school who now lived in Ohio. “I couldn’t believe it,” says Barnes. Yolanda pitched in — cleaning, answering the phone, picking up people at the airport. “There were days when I was inconsolable and she’d just sit with me and let me cry,” says Barnes. “That was just what I needed.”

Listening is key, says Val Walker, a grief educator and author of The Art of Comforting: What to Say and Do for People in Distress. “We’re taught to try to make things better, but when someone’s grieving there’s nothing to fix,” she says. Because grief impacts your emotions and your ability to make decisions during the first few weeks, treat your grieving family member or friend as if they’re in intensive care, says Nyasha Grayman-Simpson, Ph.D., a counselor in Baltimore. “Don’t ask them if they’d like to eat. Just make sure they get fed.”

People often rally around during the first weeks and months after a loss, but over time the support falls away. “That may be when your friends really need you,” says Grayman-Simpson. Indeed, her friends’ long-term support is “the reason I’m still standing,” says Manon P. Matchett, 40, of Washington, D.C., who gave birth to a stillborn daughter, Daisy, in 2008. “You want people to remember and to talk about it, because the truth is, you live with the pain every day. Telling someone, ‘I’m here for you’ means a lot.”