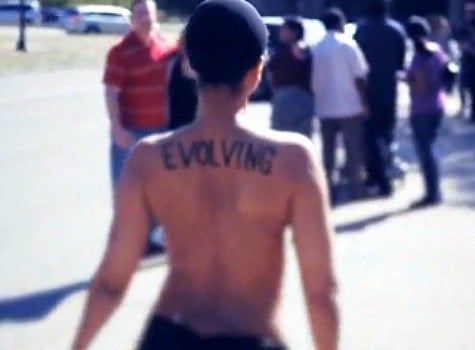

“Erykah Badu takes it all off in new video” was the headline I read one morning, so being the urban cultural connoisseur that I am, I clicked the link and proceeded to watch the video, once or twice. When we are given work that is bold and courageous, visually partaking in it is the responsible and engaged person’s practice. I, for the sake of my societal duty and calling, forced myself to sit, and watch again and again (that’s my story and I’m sticking to it). When YouTube decided to remove Erykah Badu’s “Window Seat” video I thought it to be terribly hypocritical. I immediately pulled up Alanis Morissette’s video for “Thank You,” from her fourth album, which went on to earn her a Grammy nod for best female Best Female Pop Vocal Performance. In this video in which she strolls through a city and a subway naked allowing her hair extensions to cover her breasts. In Erykah Badu’s video the words and imagery are full of socio-political themes of combating hate, but somewhat organically that important issue has given way to much broader issues about gender, sexism and racism, that when met in this moment of artistic expression has created a crucible in the conscious of all that behold it. To accuse Erykah of breaking the law by not having a permit and public indecency are legit claims but elementary at best because, the points made would be too easy and simplistic for such a complex enterprise as thinking through one’s art, the whole idea of art in culture betrays any attempt to codify said expression into any particular cultural norm. From Tyra to Serena to Oprah and Janet (hey, Janet) mainstream culture has always been obsessed with the African American female body. A body in which throughout history not only carried voluptuousness and pulchritude but the weight of denied acceptance and satisfaction from respect that has never been given. Their frames and sizes, while accepted and adored among Black society, is oftentimes met with unmerited and sad criticism from the broader pop culture in which most African American women do business. We celebrate impressionists such as Gauguin and Van Gogh. Gauguin himself was enamored with the figure of the Tahitian women most often found in his paintings, many of which hang in some of the most prestigious art galleries in the world. These women of an explicitly darker hue are generally topless. His adoration of their skin and shape bordered on obsessive and as a Brother myself, I understand. But while I can lend an “Amen” to his idea of beauty, particularly among these women, the contradiction lies in the fact that when those same women own and reclaim their own bodies for art and thought, they are rejected and labeled as obscene. Halle Berry can take her top off in conjunction with White men and it’s beautiful, but in 1993 when Jada Pinkett Smith starred in “Jason’s Lyric” with Allen Payne, I remember hearing a radio interview by a Director Doug McHenry on urban radio talking about how the establishment had a problem with the love scene because it was too Black and Jada was topless for a moment in one of the scenes. Seemingly, when African Americans seek to imagine and make powerful statements on issues of justice, politics and the like we are mostly not heard and scorned for it. When we make strides in government and business, it is most often not celebrated and yet our White brothers and sisters are allowed freedoms of speech and the like that are given to all citizens regardless of class or race. African Americans have never and will never be a monolithic community and there is no one voice that speaks for African Americans, so as other ethnic groups there can be great divisions on how we view art and what is censorship and what is obscene. Like any culture, the substratum of our conversations lie in three elements: how we see God, how we see others and how we see ourselves, all of which are subjective, as they should be. With that said, art is art and when we move to censor art we don’t understand or don’t like, then we cease to be the nation that we proudly hail and question the protectionist rights within the First Amendment of the Constitution. Black sexuality is most often not talked about in sacred and secular frameworks and is grossly misunderstood by Black people because of our lack of constructive conversations–a fact which I believe directly contributes to the high rate of HIV in our community. So, I’m not at all surprised that the broader mainstream society that promotes and exploits with exaggerated misogynistic practices for exorbitant capitalistic gain the Black woman’s body, would reject a Black woman who was not forced to take her clothes off for the camera, nor was she talked into taking her clothes off and swing on a pole or have some rapper slide a credit card down her behind. She made a conscious and faithful decision to marry embodiment and art together on her own terms for her own intellectual enterprise. If she would have posed for Playboy, would that have been OK? And why? Issues of gender and race deserve courageous conversations. We owe it to ourselves to converse without judgment, but we must be willing to engage these subjects at hand and be fearless to change the talking points for the sake of progression. So, with all that said and done, my sister Erykah, like my sister Jill Scott, has challenged us by their thoughts and dared to birth them through their words, imagery and song and simultaneously pushed the limits of discourse for us all and as we slowly and begrudgingly travel to new answers and new questions. Erykah has made us peer through the lens of her own mind and art and make us think through Badu.

Patrick D’Anzel Shaffer is a public intellectual, sacred activist and pastor of City of Faith Chicago, who fuses together his profound cultural sensitivity and passion for progressive leadership on issues of human rights, gender/race relations, HIV/AIDS prevention, teen homelessness and community mobilization. He has written for Huffington Post, MSNBC’s TheGrio.com, and Washington Post’s On Faith. He also founded “Urban Advantage” a non-profit providing life coaching & mentoring for urban youth and he’s currently working on his first book entitled “Love Again: A Spiritual Memoir.” Read More: