For Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, the issue of Washington, D.C. statehood is not only political, but personal.

“My own family has lived through almost 200 years of change in D.C. since my great-grandfather Richard Holmes, as a slave, walked away from a plantation in Virginia and made his way to D.C.,” she testified before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform.

Monday’s hearing addressed H.R. 51, the Washington, D.C. Admission Act, which aims to make the nation’s capital America’s 51st state. Holmes Norton long-standing legislative efforts began in the 1990s, with the latest measure introduced on January 4, 2021.

“We can no longer be sidelined in the democratic process. Full democracy requires much more,” she said. “Residents deserve full voting representation in the Senate and the House and complete control over their local affairs. They deserve statehood.”

An identical version of H.R. 51 was passed by the House of Representatives last year in the 116th Congress, but Republican leadership gave it no play in the Senate. However, with Democrats now in the White House and majorities in both chambers of Congress, many champions of the bill are hopeful.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and House Majority Leader Steny H. Hoyer (D-MD), have both committed to bringing the legislation to the House floor during the 117th Congress. To date, the measure has more than 200 cosponsors in the House. The Senate version of the bill (S. 51), sponsored by Sen. Tom Carper (D-DE), has at least 40 cosponsors, including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY).

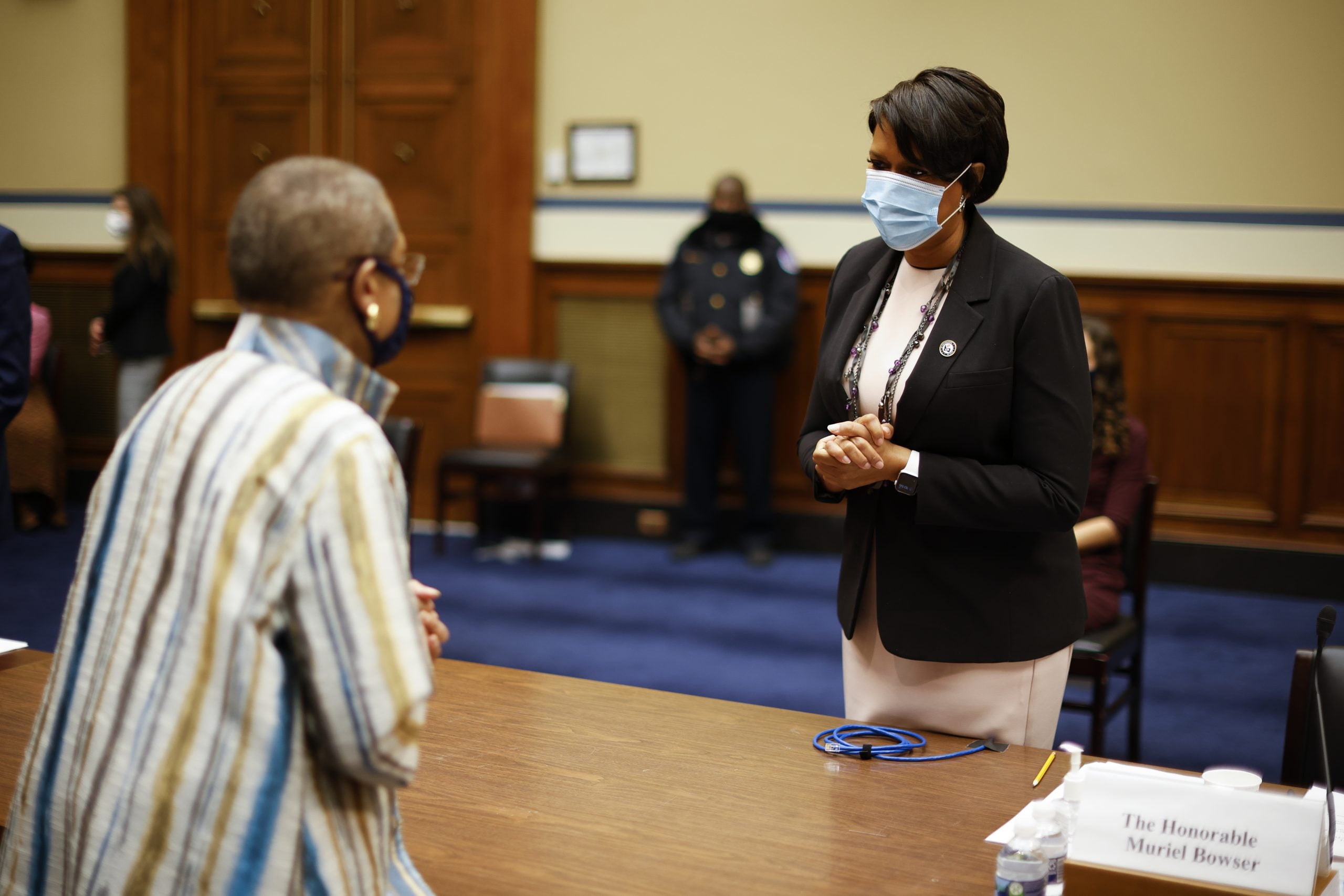

“In 2019, we came before this Committee for the first time in nearly three decades and made an irrefutable moral and constitutional case for statehood,” said Washington D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser, who also testified before the committee. “We are even more united, organized, and prepared to demand D.C. statehood now for the generations of Washingtonians who have waited far too long for full and equal citizenship.”

Washington D.C. was established in 1790, as a permanent seat for the federal government. Virginia and Maryland each ceded land for a district that from the beginning was distinct from existing states.

Today, about 712,000 people call Washington, D.C. home. While traditionally largely African American, the current population is about 46 percent Black, per U.S. Census data.

Despite its power, pomp and circumstance, Washingtonians have long lacked full self governance. Residents voted in their first presidential election in 1964, and only elected their own mayor in the 1970s, according to history posted by Destination DC, the official marketing arm of the region.

Washingtonians’ representation in Congress is limited to a non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives and two so-called “shadow“ Senators who also cannot cast votes.

Many lawmakers and advocates have characterized the quest for D.C. statehood as a civil rights issue. Although residents pay federal taxes, serve in the military and vote as do fellow U.S. citizens, they have no official say in policy decisions that impact their lives.

“The right to vote is meaningless if you cannot put anyone into office,” said Wade J. Henderson, interim president and CEO of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. “Washingtonians have been deprived of this right for more than two centuries – often on grounds that had nothing to do with Constitutional design, and everything to do with race – and remain so today.”

Until D.C. residents have a vote in Congress, he said, “they will not be much better off than African Americans in the South were prior to August 6, 1965, when President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law. And until then, the efforts of the civil rights movement will remain incomplete.”

Rep. Hoyer said the disenfranchisement of Washingtonians has had recent repercussions.

“D.C. residents have been denied critical COVID-19 emergency funding based solely on where they live,” he said. “And, at the same time, they experienced a violent insurrection [at the U.S. Capitol] incited by former President Trump which resulted in the need for thousands of National Guard troops to move into the city and erect burdensome security measures.”

Holmes Norton believes that granting the district statehood would ensure that those who live in D.C., finally have the full representation they want and deserve.

“Eighty-six percent of D.C. residents voted for statehood in 2016. In fact, D.C. residents have been petitioning for voting rights in Congress and local autonomy for 220 years,” she told the committee.

The proposed addition to the union would be called “State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth”—paying homage to Maryland-born abolitionist Frederick Douglass who spent his final years in the district.

Congress would retain authority over two square miles of the Washington that many associate with politics and tourism: the White House, U.S. Capitol complex, the Supreme Court, federal monuments, and the National Mall. That area would be called the Capital.

According to Holmes Norton, H.R. 51 has the U.S. Constitution on its side. The Constitution does not establish any prerequisites for new states, but its Admissions Clause gives Congress the authority to admit new states.

“Congress has two choices,” she said. “It can continue to exercise undemocratic, autocratic authority over the American citizens who reside in our nation’s capital, treating them, in the words of Frederick Douglass, as “aliens, not citizens, but subjects.” Or it can live up to this nation’s promise and ideals, end taxation without representation and pass H.R. 51.”

Committee Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY) applauded Holmes Norton for her “fierce leadership” and tenacity in seeking to secure full equality for district residents.

“The fact that Americans living in the District of Columbia are denied representation in Congress is a historic wrong.”