Representative John Lewis, longtime congressman and Civil Rights Movement luminary, died Friday following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old.

“It is with inconsolable grief and enduring sadness that we announce the passing of U.S. Rep. John Lewis,” his family said in a statement. “He was honored and respected as the conscience of the U.S. Congress and an icon of American history, but we knew him as a loving father and brother. He was a stalwart champion in the ongoing struggle to demand respect for the dignity and worth of every human being. He dedicated his entire life to nonviolent activism and was an outspoken advocate in the struggle for equal justice in America. He will be deeply missed.”

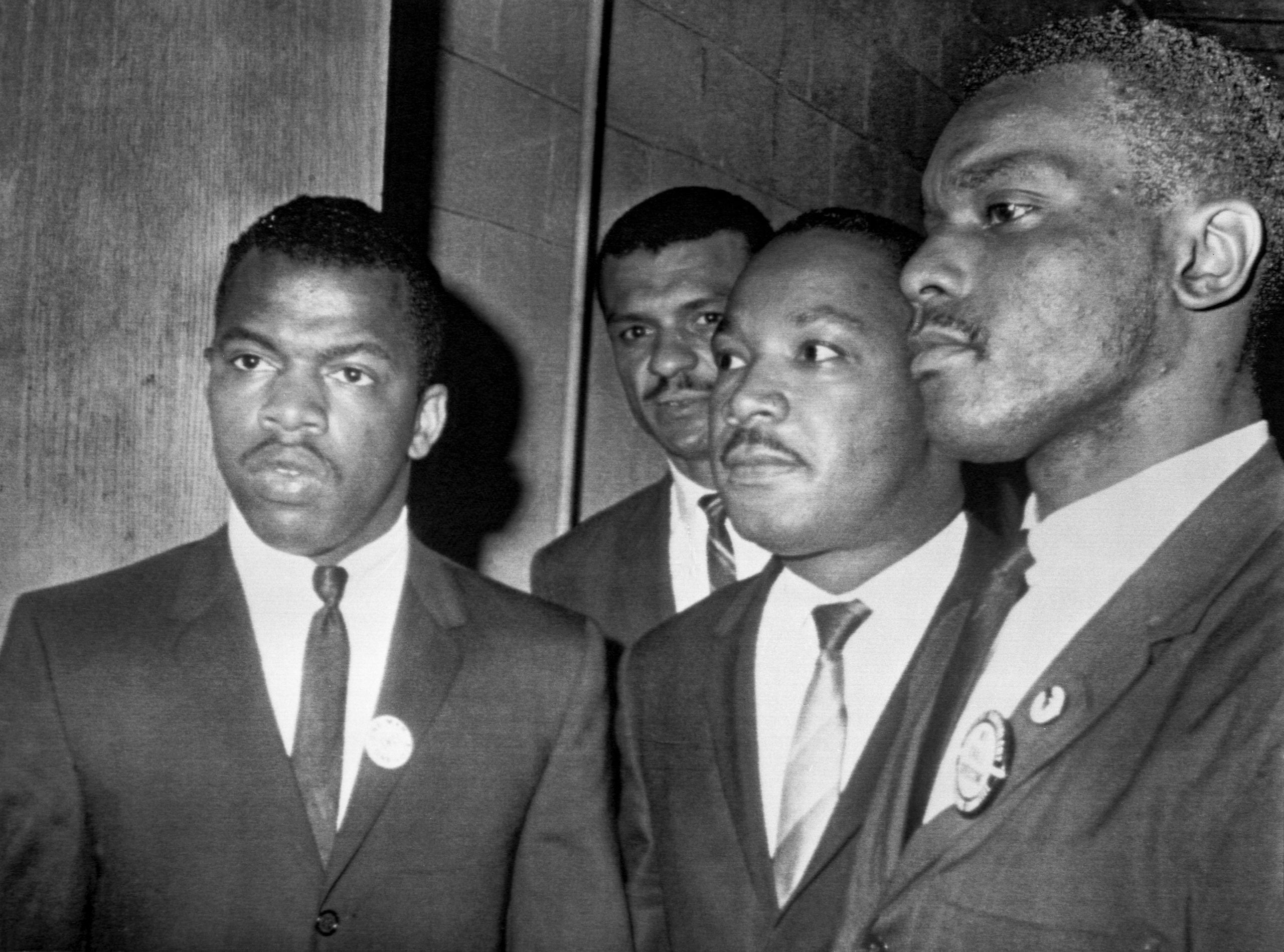

Lewis, who protested alongside Martin Luther King and braved state violence on “Bloody Sunday,” the 1965 voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, was an activist who helped galvanize some of the most important movements for racial equality. He was the last surviving speaker of the 1963 March on Washington, which he helped organize, and where King delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech.

In December, Lewis announced that he was battling stage 4 pancreatic cancer.

“I have been in some kind of fight—for freedom, equality, basic human rights—for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now,” Lewis said in a statement at the time. “While I am clear-eyed about the prognosis, doctors have told me that recent medical advances have made this type of cancer treatable in many cases, that treatment options are no longer as debilitating as they once were, and that I have a fighting chance.”

The announcement of Lewis’s death followed earlier news Friday of the passing of another civil rights leader, Rev. C.T. Vivian.

Lewis was born on February 21, 1940, to Eddie and Willie Mae Carter, sharecroppers who owned their own farm in rural Alabama. One of ten children, he was known among those who loved him as “Preacher,” after he famously baptized and ministered to the farm’s chickens. The story is immortalized in a children’s book, Preaching to the Chickens: The Story of Young John Lewis, by Jabari Asim.

“I could imagine that they were my congregation,” he wrote in his 1998 memoir, Walking With the Wind. “And me, I was a preacher.”

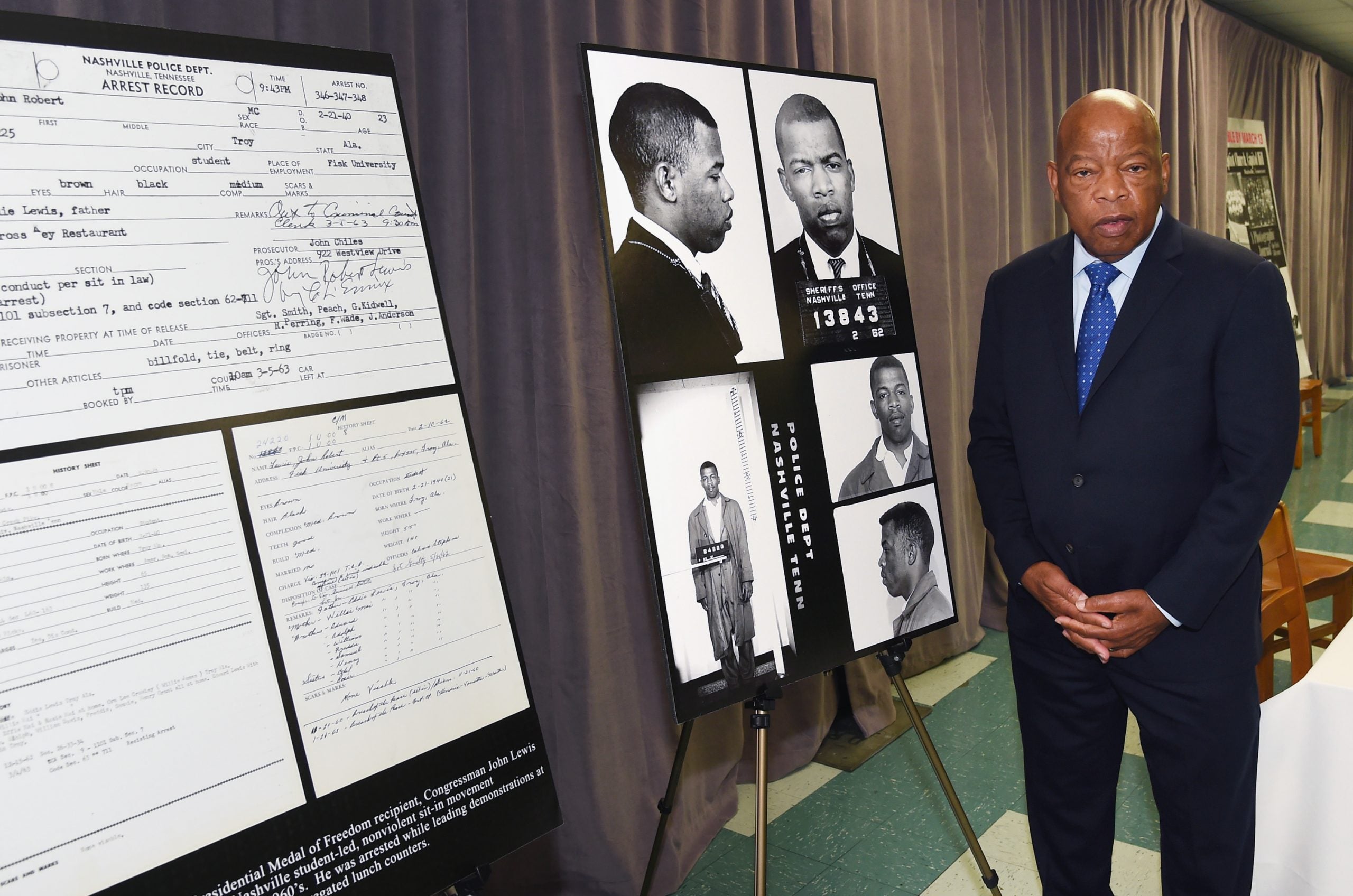

As a theological student in Nashville, he met one of his mentors, Rev. James Lawson, Jr., who taught him the meaning of civil disobedience. Soon, Lewis was among early students to protest the city’s segregated lunch counters. Later, he would help found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

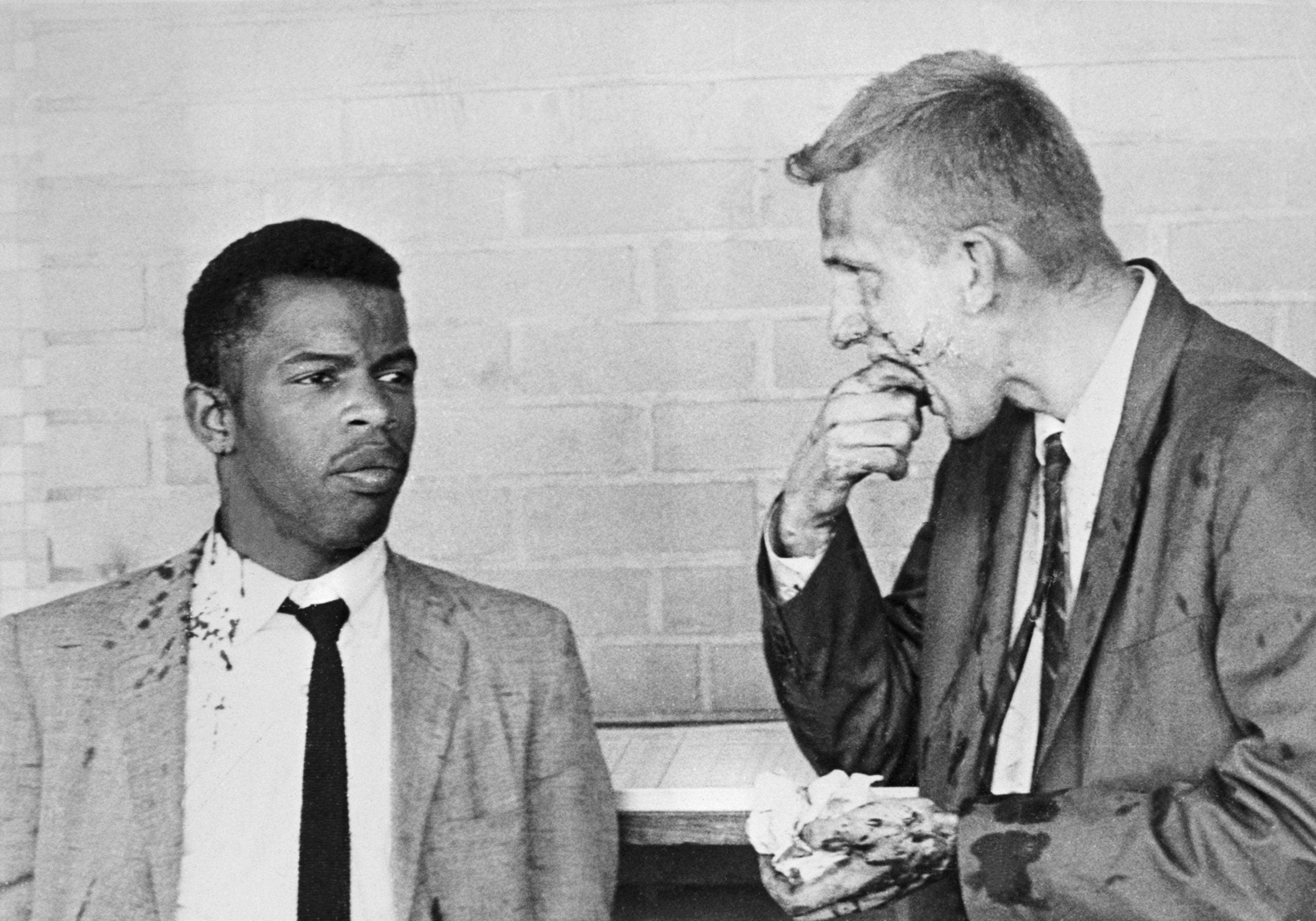

He became one of the original 13 Freedom Riders, a multiracial coalition of activists who challenged segregation across southern state lines. Lewis braved multiple brutal physical attacks against his body in his long protesting career. According to The New York Times, he was arrested 40 times over the period of 1960 to 1966, and spent 31 days in Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Penitentiary.

His friendship with Dr. King shaped his ideologies and he often described the late leader as one of his greatest sources of inspiration. At the age of 23, he helped King organize the March on Washington, where Lewis also delivered his own speech.

“By the forces of our demands, our determination and our numbers, we shall splinter the segregated South into a thousand pieces and put them together in an image of God and democracy,” he boldly declared in 1963.

Two years later, he was by King’s side as they and hundreds more marched across the now famous Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. Images of Lewis, in his tan trench coat, with his skull fractured by police, were emblazoned in history.

Decades on, the fight continues and Lewis had remained vocal throughout. Just weeks ago, in response to the nationwide protests against the police killing of George Floyd, he appeared on CBS News.

“You cannot stop the call of history,” Lewis said. “You may use troopers. You may use fire hoses and water, but it cannot be stopped. There cannot be any turning back. We have come too far and made too much progress to stop now and go back.”

In 1986, he became only the second Black man to represent the state of Georgia in Congress since Reconstruction, the Times reported. He served 17 terms and was often referred to as Washington’s moral compass.

On Friday, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi confirmed the news of his passing with the release of a statement.

“In the Congress, John Lewis was revered and beloved on both sides of the aisle and both sides of the Capitol,” she said. “All of us were humbled to call Congressman Lewis a colleague, and are heartbroken by his passing. May his memory be an inspiration that moves us all to, in the face of injustice, make ‘good trouble, necessary trouble.’ ”

President Barack Obama, who awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, penned a lengthy tribute to his longtime friend following his death Friday.

“He loved this country so much that he risked his life and his blood so that it might live up to its promise,” Obama wrote. “In so many ways, John’s life was exceptional. But he never believed that what he did was more than any citizen of this country might do. He believed that in all of us, there exists the capacity for great courage, a longing to do what’s right, a willingness to love all people, and to extend to them their God-given rights to dignity and respect.”

Earlier this year, Lewis had endorsed former Vice President Joe Biden’s campaign for the presidency.

A longtime critic of Trump, in one of his final high-profile speeches, Lewis decried the President during the impeachment hearings last fall.

“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something,” he said. “Our children and their children will ask us ‘What did you do? What did you say?’ ” While the vote would be hard for some, he said, “We have a mission and a mandate to be on the right side of history.”

Lewis’s wife, Lillian Miles, died in 2012. He is survived by their son, John Miles Lewis.