There have been many loaded, anti-Black discussions about personal responsibility and how Black people manage our Black lives, including our health, during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, not nearly as much collective concern—and judgment—has been expended to call out white supremacist institutions and instructors that pathologize Blackness without examining the structural unwellness of this nation.

During the course of producing this series on COVID-19 and its impact on Black America, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with and be in (socially-distanced) community with some of the sharpest minds, biggest hearts, and committed organizers of this generation. However, it was the words of Mr. Robert Taylor of Reserve in St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana, that have resonated with me for months—and will do so for a lifetime.

Located in Cancer Alley, positioned geographically and racially to be more vulnerable to natural disasters, all while witnessing medical apartheid and routine police violence, Mr. Taylor has experienced some things—more than anyone should have to experience. I asked him did he feel that his life mattered in this country—to this country. He waved away talk of feelings, assuring me that didn’t feel that his Black life didn’t matter to this country; he knew his Black life didn’t matter to this country because he had never been shown otherwise. Not only has he seen several George Floyds in his almost eight decades of living, he told me: “I know my great-granddaughter could be Sandra Bland.”

Taylor, who also survived Hurricane Katrina, tells me this from his home in Reserve, where he fights against a chemical plant that has been allowed to poison his community for years. Not surprisingly, St. John the Baptist Parish once had the highest COVID-19 death rate per capita than anywhere else in the nation.

These are the interlocking means of oppression, exploitation, neglect, and death that many Black communities face—still. This is what environmental injustice can look like: creating and sustaining an environment hostile and inhospitable to the safety, health, and wellness of Black people, which ultimately ends in our premature deaths.

As the coronavirus continues to devastate the United States, Black Americans are still disproportionately considered essential workers—and less likely to be privileged enough not to work—which increases likelihood of exposure. According to a 2020 Gallup poll, Black Americans are also less likely to seek medical care due to concerns about cost and more likely to face discrimination if they do seek treatment.

This is not a new reality. Still, it took much too long for so-called political leaders and experts to realize what Black people already knew: COVID-19 would disproportionately impact us because of the environmental, economical, medical, social, and political violence many of our communities already endure.

Writing for ESSENCE back in April, Daniel E. Dawes, JD, director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine, and author of The Political Determinants of Health, taught us:

“We know that the underlying factors, such as asthma, heart diseases, hypertension, lung disease, cancer, HIV/AIDS, diabetes and obesity, strike disproportionately within communities of color. As a result, they are at greater risk for complications from COVID-19. The inequities that pre-date COVID-19 did not suddenly become inapplicable, which could result in the U.S. ending up with major disparities in who dies from the coronavirus.

“Minorities and other vulnerable communities still contend with neighborhoods that are largely devoid of necessary resources, and they still contend with the political determinants or drivers that created, perpetuated and exacerbated these health inequities,” Dawes continued. “The lower a person’s socioeconomic status, the more limited their resources and ability to access essential goods and services, and the greater their chance of suffering from premature death.”

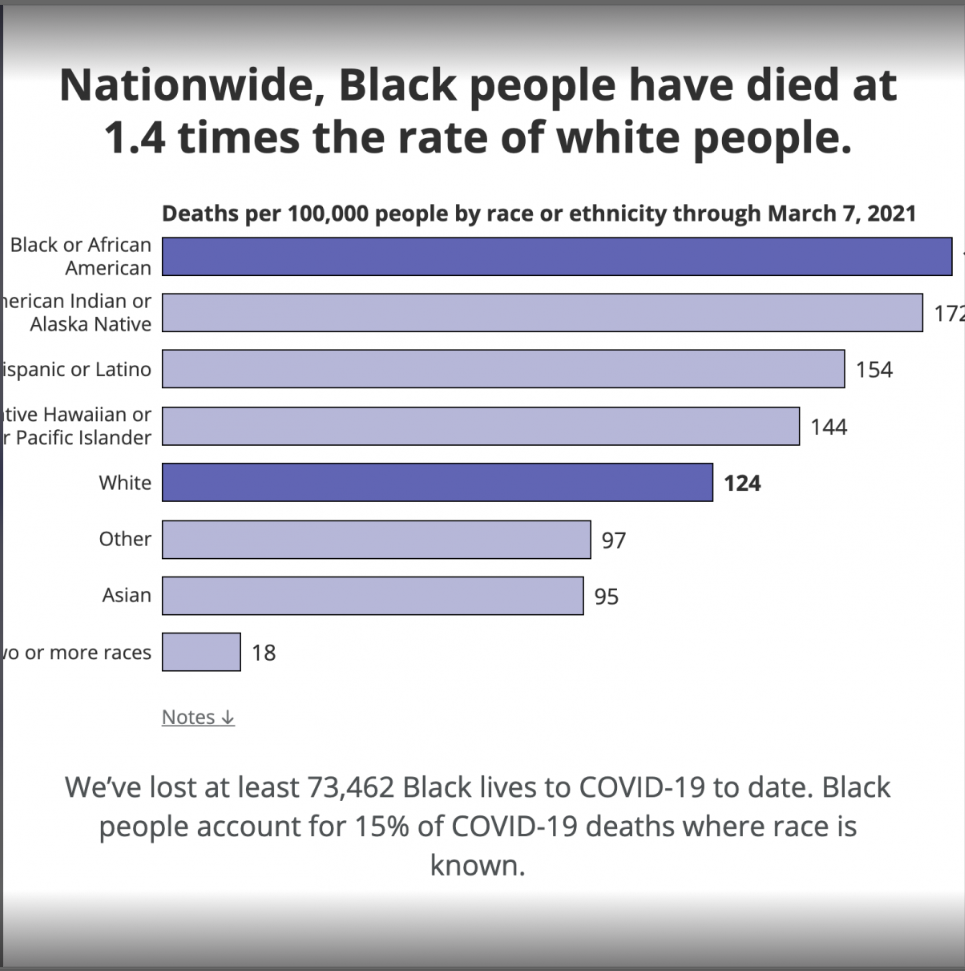

To date, there have been nearly 74,462 Black lives lost to COVID-19, according to the COVID Racial Data Tracker. Nationwide, Black people are dying at 1.4 times the rate of white people.

In Part III of our COVID-19 series, we focus on environmental injustice, one of the most critical issues that we face. We also talk about food apartheid (food redlining) and resource deprivation—and the toll on Black bodies. From Cancer Alley and Central Appalachia, to other rural communities throughout the south as well as densely populated urban areas like Detroit, we live in a nation that calls symptoms the illness and pretends the illness doesn’t exist. No more.

It took too long for so-called political leaders and experts to realize what Black people already knew: COVID-19 would disproportionately impact us because of the environmental, economical, medical, social, and political violence many of our communities already endure.

Featured in this episode are:

Biba Adams, a Detroit-based writer who has lost her aunt, mother, and grandmother to COVID-19

LaTosha Brown, activist and co-founder of Black Voters Matter Fund

Joia Crear-Perry MD, FACOG, founder and president of National Birth Equity Collaborative

Ashanté M. Reese, PhD, co-editor of Black Food Matters: Racial Justice in the Wake of Food Justice and author of Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C.

Maurice Sholas, MD, PhD – Principal, Sholas Medical Consulting, LLC

Robert Taylor, community organizer and founder of Concerned Citizens of St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana

Ash-Lee Woodard Henderson, co-executive director, Highlander Research and Education Center

—

WATCH Parts I and II of “COVID-19’s Impact on Black Communities”: