Capitalism isn’t the boogeyman; it’s the way of American business. However, the system does demand hard choices. No matter the sector, every company is ultimately in business to produce one thing—profit. Whether industry leaders subscribe to stakeholder capitalism, shareholder capitalism, or conscious capitalism, the business of business comes down to capital. So, in times of economic uncertainty, spending that contributes to the bottom line is prioritized, and that which doesn’t isn’t.

The problem is hard choices often come with ugly consequences, and in times of economic headwinds, diversity initiatives frequently end up on the chopping block. Still, the necessity of capitalism doesn’t compensate for a history of structural discrimination. Deprioritizing promised DEIB (diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging) commitments put more at risk than the just bottom line. It calls into public question the sincerity of such commitments.

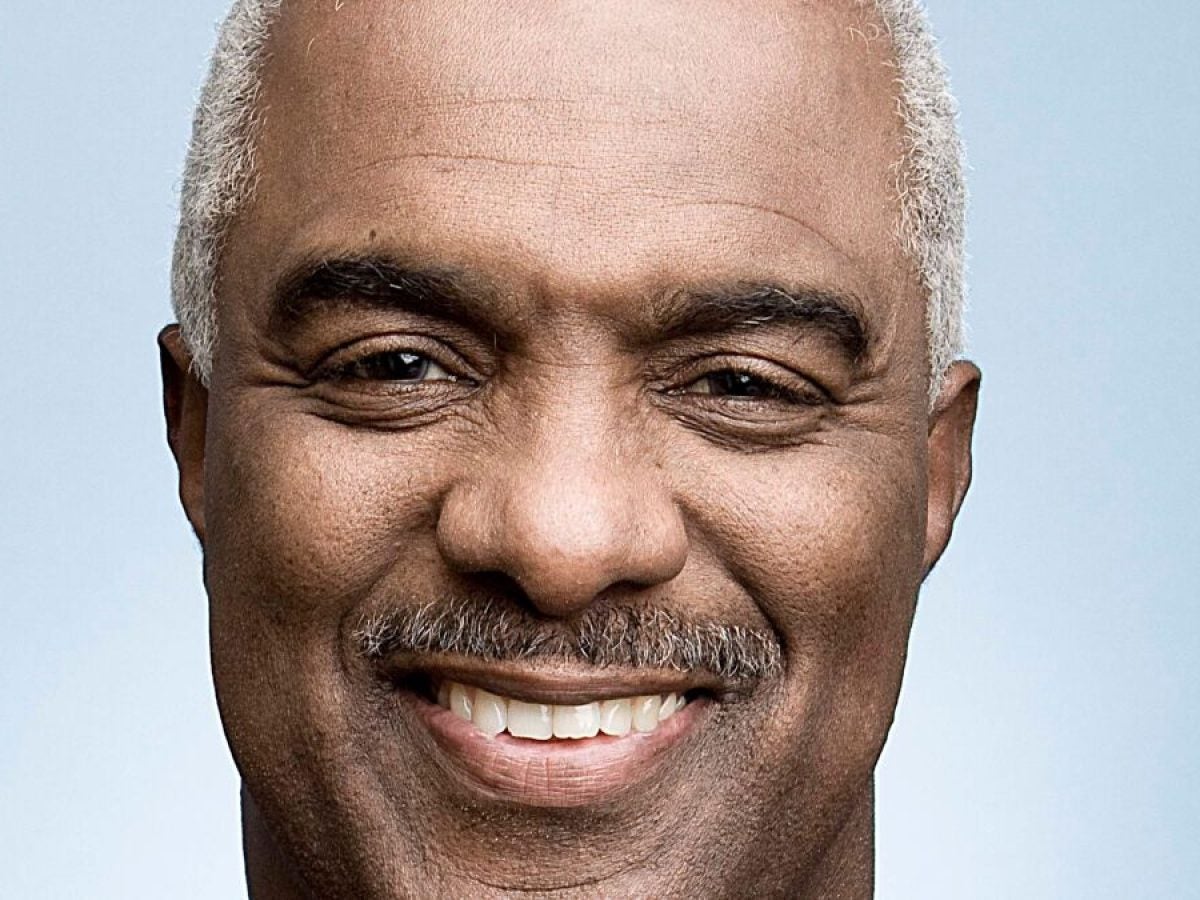

Corporate America’s teetering on DEIB commitments frays an already tattered relationship with historically marginalized communities. For the tech industry in particular, the deterioration of trust is justified. Listings for DEIB roles declined 19% in 2022, and mass layoffs have sometimes wiped out entire D&I departments—all of which undermine pledges made by the sector to boost underrepresented talent in its leadership ranks. As large swaths of big tech render their corporate diversity promises all talk and no action, it calls into question the credibility of commitments across all industries. But Forest T. Harper, President and CEO of INROADS says, not so fast.

Harper—who heads the nation’s largest non-profit feeder of diverse talent into corporations, says the cynicism of Black and Brown communities is not without merit. Still, he has 7 billion reasons to believe that the summer of 2020 was the DEIB game-changer it promised to be. According to a new Mckinsey report, corporate America has topped over $7 billion in DEIB-related efforts since the unjust murder of George Floyd. Public commitments project more than $15.4 billion in spending by 2026. For Harper, it’s just one of many data points that bolster his confidence.

“What we saw in 2020 after the unfortunate deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, was unprecedented [in terms of corporate diversity commitments]. Number one, the three to five-year plans were made public. That’s the first indicator that corporate America has gotten serious. The second is they were funded, go to the Mckinsey data, the commitments were legit,” Harper told ESSENCE. “It’s the first time we have seen such mass, analytical, legitimate tracking to an accountable number, made in public,” he said.

While significant investments in corporate diversity initiatives demonstrate good faith, the impact of that spending has yet to be seen. Harper said that’s to be expected. “A pivot of this magnitude happens over multi-years,” he said. His confidence in corporate commitments to DEIB is not only informed by data. As a strategic partner building diverse talent pipelines into several Fortune 500 companies, his purview behind the corporate curtain provides added insight.

I asked the INROADS leader and Forbes Nonprofit Council member to lend some perspective on the state of corporate diversity. He shared why corporate America has to address DEIB from the inside out if they want to see results, what is required of organizations to make the necessary cultural shift, and how INROADS is partnering with top companies to support the transition. Harper also revealed why he believes now is the opportune time to significantly narrow—maybe even close the racial wealth gap.

Corporate America’s inside-out problem.

Diversity makes dollars and sense for corporations. Organizational diversity is correlated with better financial performance, and what’s more, the public is increasingly holding businesses to account by choosing to spend with companies that demonstrate a commitment to social responsibility. In more ways than one, corporate investments in diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging contributes to organizational bottom lines. Still, despite the proven competitive advantage given to diverse organizations, the implementation of diversity initiatives is often tricky to embed within organizations.

As it turns out, policy is easier to change than hearts and minds. The reality is businesses are staffed with people, some of whom may resent all the hoopla around diversity, equity, and inclusion. Personal biases—consciously or unconsciously—factor into hiring decisions, advocacy choices, and the overall treatment of people of color within organizations.

Harper says internal push back is often to blame for the disconnect between DEIB commitments made at the corporate level and their often lackluster implementation. “They [organizational leaders] found out they have to fix the inside first,” he said. “If you don’t fix the inside—meaning your current state of promotions, your current state of retention, your intern converts, equal pay for women—results will be delayed.” Harper says changing organizational culture is difficult but not impossible. “The shift requires disruptors willing to challenge corporate social norms,” Harper said.

Disrupting corporate culture.

Capitalism isn’t in the business of charity, and Black and Hispanic people aren’t looking for a handout. Investments in cultivating diverse talent aren’t discriminatory—on the contrary, it’s the history of structural discrimination that makes such deliberate investments necessary. Harper, a former senior-level executive of an S&P 500, understands the nuances of business leadership. He also understands the necessity of disruption. The INROADS organization he now helms was founded on it.

For Frank C. Carr, the visionary who founded INROADS in 1970, the organization completely disrupted his life. “This was a stately white gentleman out of the class in 1944. He was a corporate executive, well respected in his community. But, he decided to take some kids on a school bus to The March on Washington. After hearing Dr. Martin Luther King speak, he came back and created INROADS because he wanted to disrupt the norm. He wanted to create inroads for Blacks and Hispanics to enter corporate America, and the middle class,” Harper shared.

INROADS is still in the business of disruption. Companies including Lockheed Martin, PricewaterhouseCoopers, and Pepsi Beverages Company, partner with the nonprofit and embrace its elite pool of diverse talent. Some seek consultation from the organization on how to build an internal culture of inclusion and belonging to retain the diverse talent they recruit.

A proven formula for diversity.

“We have got to take a step back and really examine systems that have marginalized people and focus on changing those systems,” Melinda King, Head of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at leading consumer genetics and research company 23andMe, said in an earlier interview with ESSENCE. “How can you truly have a diverse recruiting process when you are asking for qualifications and experiences that most individuals from communities that have been marginalized would not have had access to because of systemic problems?,” she said.

Harper wholeheartedly co-signs the sentiment. INROADS works with organizations to break up cultural norms that may have the unintended effect of barring truly exceptional candidates. “The norms are things like pedigree, what college a potential candidate attended, even their type of degree,” he said. Many companies pigeonhole their recruitment to certain campuses for certain things. As an example, Harper says, “HBCU recruitment for diverse candidates is phenomenal but it’s not the only place to find Black and Hispanic candidates. The University of Michigan, has more Black students than 20 HBCUs,” he said.

Additionally, he says, companies also benefit from the regular revaluation of job requirements. To that end, he encourages the following line of questioning: “What are you looking for? What is required to perform that job today? Is this qualification even normal anymore?” he said.

Harper also encourages businesses to cast wider nets. “If you’re telling me you’re looking for Ph.D. candidates to go into Big Pharma, and you’re not having any. Why not go to the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore, which has the largest number of Animal Science majors? Or, check out the University of Virgin Islands with one of the largest marine biology programs,” he said, “So much of it is just about getting out of the ruts we all find ourselves in.”

Many organizations invested in DEIB appreciate a fresh set of eyes to help confront organizational blind spots. Several have opted not to traverse their diversity recruitment journey alone. INROADS works hand-in-hand with its partner organizations to partner in the recruitment of diverse candidates and traverse internal barriers to inclusion where needed. It’s a winning formula. In 2021, the organization placed 2,265 diverse interns with partner organizations. 65% of graduating interns accepted job offers in those organizations.

Narrowing the wealth gap.

Harper says the impact of INROADS vetted diverse candidate pipelines and corporate America’s investments in DEIB, is far-reaching—a win-win for corporate America and communities of color.

During an INROADS gala a couple of years ago, Harper met a realization that led him to expand his view of just how far-reaching that impact could“Martin Luther King III was the guest of honor at this gala. He got up to the podium to address the room, and said, ‘My mother [Corretta Scott King] told me about INROADS. She said INROADS built the Black middle class in America,’” Harper recalls.

That statement reverberated in Harper’s head: “INROADS built the Black middle class in America.” Could that be true? While he understood the organization’s impact, he hadn’t quite grasped it to this extent. Harper recalled, “He [Martin Luther King III] challenged us to do the research, to trace the correlation between INROADS internships and the upward mobility of Black families.” Harper, and the INROADS team took the challenge to heart.

Through a grant provided by MetLife, the organization commissioned WealthEngine, The Federal Reserve Bank Of St. Louis, and Ariel Investments to track all 35,000 alums who passed through the INROADS organization since its founding in 1970. What they discovered was astonishing. “We took 1000 INROADS alum versus 1000 white executives. We compared their net assets, net income, net worth, and homeownership rates. The data showed 40% of INROADS alum outpaced their white counterparts in net worth and net asset. But guess what? 12% of the enrolled alum outpaced their white counterparts in home ownership,” Harper said. Completely taken aback by the impact, now documented, Harper took it a step further.

“I picked up the phone and called McKinsey economist Shelley Stewart. I asked if he could examine what economic impact the organization could make now and in the future,” Harper shared. “We particularly wanted to know what it would take to put a dent in the racial wealth gap for Black and Hispanic families.” The outcome of the reporting was revealing. “Basically, if INROADS’ were to scale our impact ten times, the organization could make a $750 billion impact in communities,” Harper said. For Harper, the final data point sparked a new ambition. The reporting outlined a tangible path, albeit aggressive, that could change the game for Black and Brown communities.

The combined effect of billions in corporate DEIB investments, along with INROADS’ continued growth in partnerships, and its investment in preparing young leaders for the future of work, could realistically carve a path toward narrowing, and potentially even closing America’s racial wealth gap.