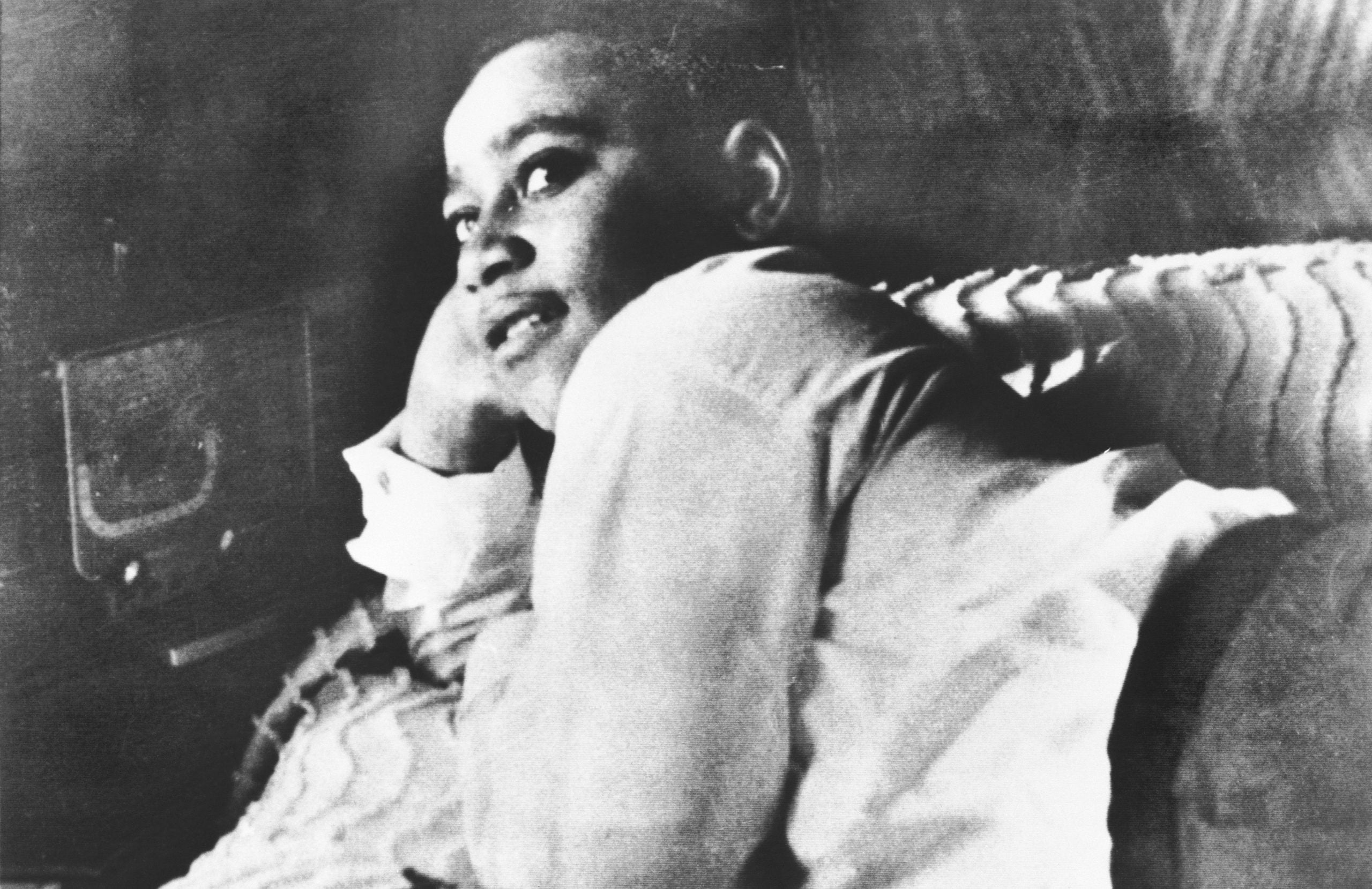

The tragic events that took place after teenage Emmett Till left his mother’s house in 1955 still reverberate to this day.

And while his accuser finds herself in the news for recently discovered warrants and unpublished memoirs, the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund will use its efforts to rehabilitate the building he called home.

According to the Associated Press, the organization will receive a share of $3 million in grants, which are being distributed across other important pieces of Black American history. The funds will be allocated to other places, such as a bank founded by a man described by Booker T. Washington as the “most influential businessman in the United States,” the first Black Masonic lodge in North Carolina, and a school in rural Oklahoma for the children of Black farm workers and laborers.

The money will also help restore the Virginia home where Black athletes such as Arthur Ashe and Althea Gibson went from unknown talents to globally recognized champions.

Brent Leggs, executive director of the organization that is in its fifth year of awarding the grants, said the effort is intended to fill “some gaps in the nation’s understanding of the civil rights movement.”

Till’s brutal slaying at the behest of a white woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, helped to spark the civil rights movement across the country. The Chicago home where Mamie Till Mobley and her son lived will receive restoration, including renovating the second floor to what it looked like when the Tills lived there.

“This house is a sacred treasure from our perspective, and our goal is to restore it and reinvent it as an international heritage pilgrimage destination,” said Naomi Davis, executive director of Blacks in Green. This local nonprofit group bought the house in 2020. She said the plan is to time the 2025 opening with that of the Obama Presidential Library a few miles away.

With attention from all sides being focused on the Till family, Leggs found it particularly important to shine a light on Mamie Till Mobley after her efforts to show the world what racism looked like mainly went ignored by white America.

Emmett’s open casket funeral, once put on display, influenced thousands of mourners who filed by the casket and the millions more who saw the photographs in Jet Magazine. As history would have it, Rosa Parks was one of those people who were deeply impacted by the cover and would later refuse to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus to a white man about three months later, which remains one of the pivotal acts of defiance in American history.

It is this moment that highlights the importance of maintaining Black American history at the risk of it vanishing if not protected.

In that same Associated Press report, it was noted that in 2019, when the Till house was sold to a developer, the house was falling into disarray before the city of Chicago granted it landmark status. The glass-topped casket that held Till’s remains—which was only donated to the Smithsonian Institution because it was discovered a decade earlier—was rusting in a shed at a suburban Chicago cemetery where it was discarded after the teen’s body was exhumed years earlier.

“We got to remember what happened, and if we don’t tell it if people don’t see (the house) they’ll forget, and we don’t want to forget the tragedy in these United States,” said Annie Wright, 76, whose late husband, Simeon, was sleeping when his cousin, Emmett, was abducted.