If you’ve read Turner House — the debut novel by Angela Flourney that was shortlisted for a National Book Award for Fiction (and featured briefly in the latest season of Insecure) — you may already be familiar with the 1967 Detroit uprising on which Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit is based.

With a gentle hand, Flourney weaves in scenes of despair, chaos, and survival, while showing a family struggling to, literally, pick up the pieces left in the rubble of a fight Black people have long waged against injustice.

Though a fictional account, the tale mirrors the reality for many African-Americans who survived that era and those who encountered police abuse and a gross lack of protection in the criminal justice system in the decades prior.

Leading up the the 1967 uprising, Black people in Detroit engaged in a variety of civil disturbances, with major rebellions in 1833, 1863, and 1966, to send a strong message to whites who had been the source of economic and political subjugation.

The disturbance in 1967, however, proved to be one of the most impactful in shaping Detroit’s current landscape and the anti-Black sentiments that catalyzed White flight from a city that was once a beacon of hope for Blacks during the Great Migration. And while Bigelow’s film focuses on one horrific act at the Algiers Motel — where police killed teenagers Carl Cooper, Fred Temple, and Aubrey Pollard and tortured many others — the events that lasted over the five-days is a crash course in America’s dark history with state violence and the overall oppression of Black and Brown people.

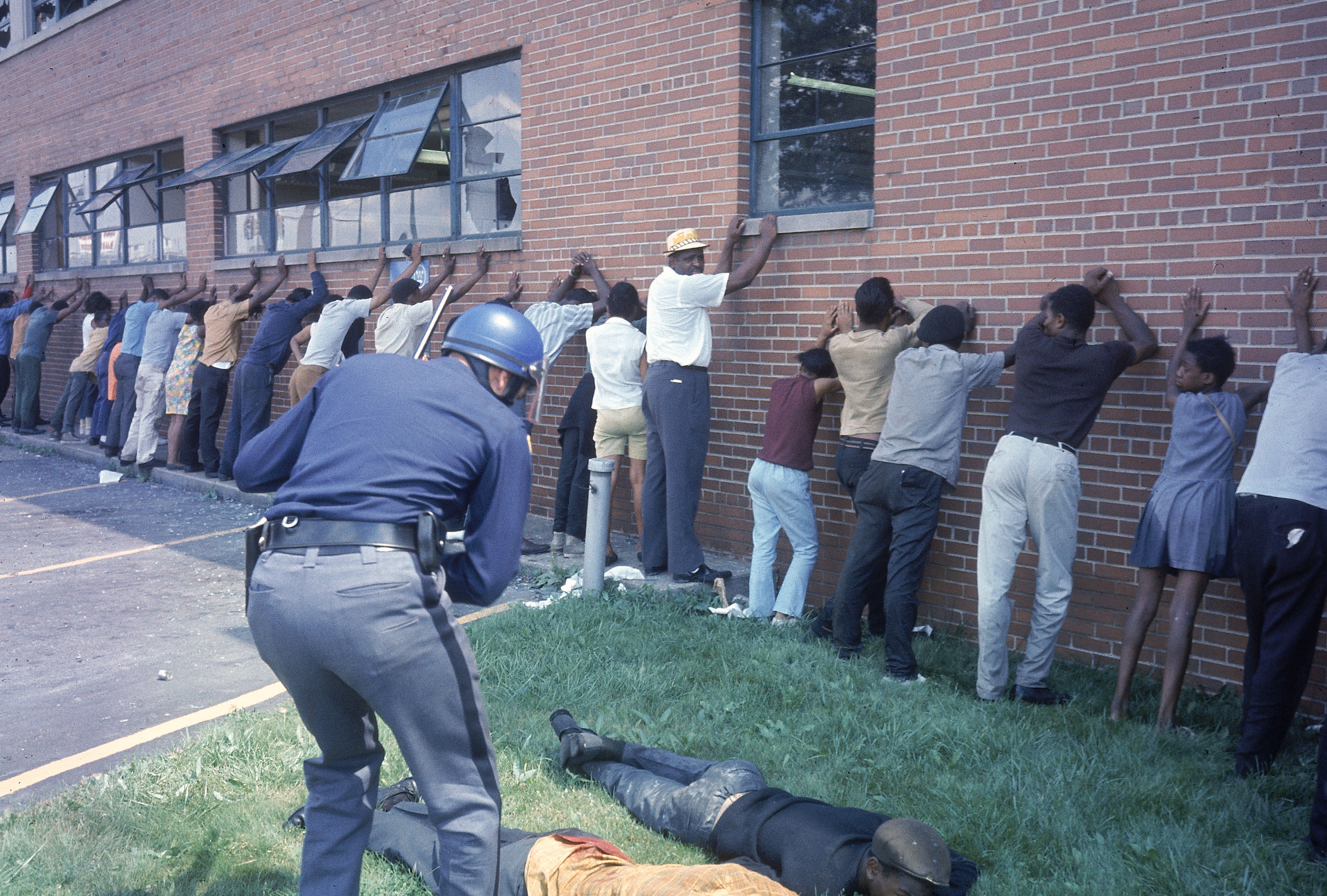

On July 23, 1967, police raided an illegal after-hours bar occupied by Black patrons on Detroit’s west side.

While officers started off removing some club patrons from the establishment through relatively mundane arrests, police tactics escalated into aggressiveness, including pushing and twisting the arms of women, according to a detailed account shared by the Detroit Free Press.

With Black people around the country departing from nonviolent civil rights tactics of the early 1960s and engaging in more assertive measures to confront white violence, such as Oakland’s Black Panther Party founded a year prior, the crowd at the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount on Detroit’s west side felt emboldened.

One of those in the crowd was 19-year-old Bill Scott, whose father owned the club.

As throngs of officers ascended outside the bar, billy clubs in hand, Scott grabbed a bottle. He threw it at one of the officers. The month before, when cops raided his father’s club for the second time, an officer hit him in the head.

Scott’s act of defiance precipitated a hail of thrown objects, and the beginning of the 1967 rebellion.

In 1967, 25-30 percent of Black youth were unemployed. Conditions in urban areas for Black people were not mirroring the lofty goals of the Civil Rights Acts that Congress had passed in 1964. Unrest in over 159 protests — all originating with frustrated Black residents — erupted in urban cities around the country that summer.

Detroit’s — with deaths of 43 people and destruction of 2500 stores — is considered the worst among them.

The causes that led to Detroit’s civil unrest were not unique. The original encounter with police officers on the fateful July day were mundane enough. But, like uprisings witnessed most recently in Ferguson, Missouri and Baltimore, it was a response fueled by Black people at their tipping point.