An order from Dominican Republic government officials has left hundreds of thousands of Haitian immigrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent at risk of deportation.

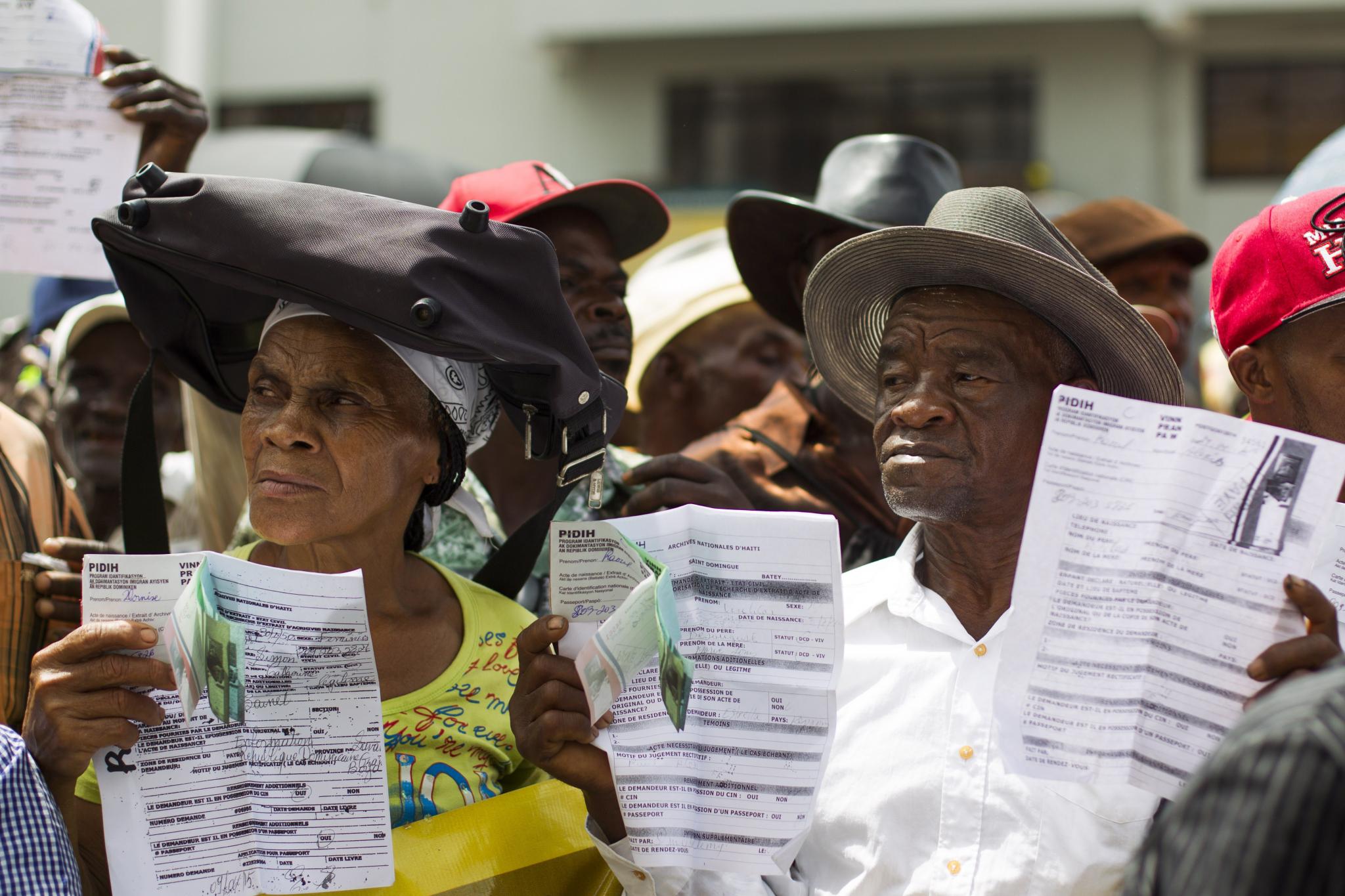

Citizens and immigrants of Haitian descent, many of whom are migrant workers, have until tomorrow to file paperwork that could help them secure residency permits. To receive a permit, they must produce a form of identification, such as a birth certificate, passport or a work permit from their employer. But the Dominican government can decide at its discretion whether it will accept an individual’s ID, regardless of its validity.

In 2013, citing overcrowding from the influx of Haitian immigrants to D.R. after the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake, the Dominican government tried to revoke the citizenship of children who had been born as far back as 1929 to Haitian parents. After receiving international backlash, the government backed down, but in 2014 introduced a revised iteration of the order, which now requires people of Haitian descent to apply for temporary residency permits. Many of these people were born in the Dominican Republic, but have had their birth certificates deemed invalid by the government.

“The signals are clear,” Beneco Enecia, the director of Haitian immigrant advocacy group Cedeso, told The New York Times. “The Dominican government is setting up logistics, placing vehicles and personnel to start the process of repatriation.”

An estimated 240,000 residents have begun the residency permit process, while more than 500,000 are at risk of being deported to Haiti. Those who have started the paperwork have been given a 45-day grace period to obtain the proper identification and complete the registration. If they provide all of the necessary paperwork, government officials will consider granting them residency. So far, only 300 people have received permits.

Many of the Haitian descendants at risk of deportation were born and raised in the Dominican Republic, and have never visited Haiti. If their residency is revoked, they say that they will be left stateless.

“If these massive deportations occur, will they include—by mistake—people who were born in the Dominican Republic?” said Lilian Gamboa, a Dominican civil rights activist, said to the Times. “Will they follow the standards of international law? Will Haiti be able to receive this number of deportees? And what would their status be in Haiti?”

Dominican officials say that if people of Haitian descent fail to file their paperwork on time, agents will work with each individual to discuss a plan of action. But both Haitians and Dominicans are skeptical of the government’s screening methods.

“The criteria is based on racial discrimination,” Enecia said to the Times. “Fear, desperation and anguish are the expressions of the people. They feel helpless.”