This article originally appeared on Time.

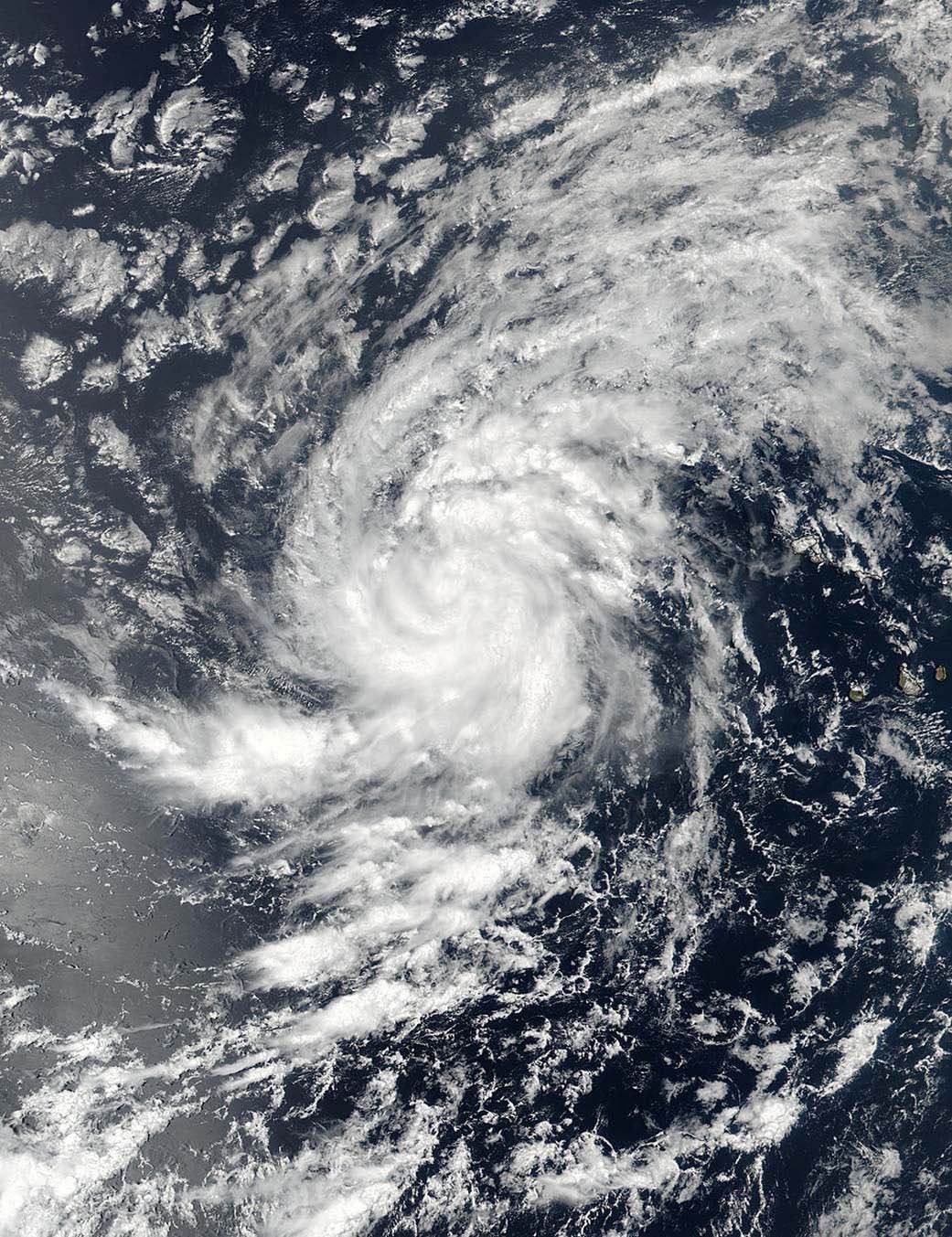

As the United States continues to reel from the effects of Hurricane Harvey in Texas, U.S. meteorologists have turned to monitoring Hurricane Irma, which made landfall in the eastern Caribbean and is barreling towards Florida. Hurricanes are notably unpredictable, but there is at least one thing about the storms that’s easy to know in advance — their names.

The reason for those names is simple: Human names are easier to remember than numbers or meteorological jargon. These days, the World Meteorological Organization maintains and updates six alphabetically-arranged lists for naming Atlantic tropical storms. Each list has 21 names each, meaning that each name could theoretically get repeated every seventh year.

(Upcoming lists can be found here.) The Geneva-based organization says the system of relying on lists has been in place since 1953. If there are more than 21 storms in a season, then storms start getting names from the Greek alphabet. Names of particularly destructive storms are retired out of respect — for example, Matthew, Katrina, Sandy and Mitch are off the table — and in those cases, a new one will be chosen at the WMO’s annual meeting (though they’re not looking for suggestions). Weather centers in other countries might use a name more familiar in the regions where the storms hit; for example, a 2009 typhoon in the Pacific was known as Ketsana in Japan and Ondoy in the Philippines.

Throughout most of history, before such a system existed, what experts called hurricanes varied widely. In the 18th and 19th centuries, some storms were named for the geographic locations they hit, while others were named for the saint’s feast day on which they made landfall, as was the case with 1876’s San Felipe hurricane. There were at least two in the 19th century named after specific men. The 1834 “Padre Ruiz” hurricane hit the Dominican Republic on the same day as the burial of a beloved priest of that name, while “Saxby’s Gale,” which hit Canada in 1869, was named for the British naval lieutenant said to have predicted the exact day the storm would hit.

The origins of the modern naming system are often traced to the late-19th century Australian meteorologist Clement Wragge (known as “Wet Wragge” to some), who started out using letters of the Greek alphabet to keep track of hurricanes and then switched to popular girls’ names in the South Pacific, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). A section of Atlantic Hurricanes by Gordon E. Dunn and Banner I. Miller, quoted by the agency, claims that when Wragge didn’t get a job he wanted as director of Australia’s weather bureau, he sought revenge by naming hurricanes after the politicians who had not supported him. “By properly naming a hurricane, the weatherman could publicly describe a politician (who perhaps was not too generous with weather-bureau appropriations) as ‘causing great distress’ or ‘wandering aimlessly about the Pacific,’” the authors note.

Wragge’s weather bureau would eventually close, but that wouldn’t prevent his idea from striking a chord: decades later, author George Stewart took a page from Wragge for a bestselling novel. “In his 1941 novel Storm, a junior meteorologist named Pacific extratropical storms after former girlfriends,” according to NOAA. “The novel was widely read, especially by US Army Air Forces and Navy meteorologists during World War II. When Reid Bryson, E.B. Buxton, and Bill Plumley were assigned to Saipan in 1944 to forecast tropical cyclones they decided to name them (à la Stewart) after their wives.”

The idea of naming hurricanes after women is believed to have been less confusing than naming them by the military’s phonetic alphabet, which had also been tried, so the U.S. Weather Bureau made it official policy in 1953.

“People may think it’s an easy job, but it isn’t,” Norman Hagen, a planning official in the U.S. Weather Bureau, told TIME in 1955, because, as he explained, he couldn’t use names of states, cities, months, time of day (i.e. Dawn, Eve) or names that sounded like weather formations (Gail). He pored over baby-naming handbooks to come up with the 1955 list of names, which ran from Alice to Zelda.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The joking implications of that system were not lost on its users, with subtle political insults giving way to a common wisecrack about how hurricanes and women were both hard to predict, as the Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones puts it.

But not every American thought that joke was a funny one.

By the late 1960s, as women spoke out on gender inequality throughout society, so too did they speak out against the gender inequality of hurricane names. For example, at the Republican National Convention in Florida in 1968, activist Roxcy Bolton approached National Organization for Women (NOW) founder Betty Friedan about the issue, as Friedan would recall in her memoir. By March 1970, Bolton had become a Vice President of NOW and continued to lead on the issue, writing a letter to the National Hurricane Center in Miami requesting that officials “cease and desist” from using female names to describe hurricanes, which “reflects and creates an extremely derogatory attitude toward women,” who “deeply resent being arbitrarily associated with disaster.” The letter also pointed to a dictionary definition of hurricane as “evil spirit” to help back up its point. In another letter, dated New Year’s Day 1972, she called for storms to be named after U.S. Senators because they “delight in having streets, bridges, buildings” named after them.

She visited the National Hurricane Center in Miami, and told weather experts that storms should also be called “himicanes” because “I’m sick and tired of hearing that ‘Cheryl was no lady as she devastated such and such a town,’” the Associated Press reported on Jan. 20, 1972. When another list of female names came out that spring, a headline for a UPI report published in the New York Times read, “Weather Men Insist Storms Are Feminine.” The paper also reported on Bolton’s belief that weather officials didn’t even realize the single-gender system was “casting a slur on women,” even as Arnold Sugg of the National Hurricane Center insisted that her opinion was overblown and not representative of the general public. “A lot of women even ask us to name hurricanes for them,” he added.

But, in 1978, the agency finally changed course.

NOAA Administrator Richard A. Frank announced hurricanes would start getting male names, too, due to the work of Bolton and NOW, as well as other women outspoken on this cause, Deborah Yates and Patricia “Twiss” Butler. “In this day in age, it was the sensible thing to do,” he told the New York Times that May.

The first hurricane given a male name would be “Bob,” which hit the Gulf Coast region on July 11, 1979.

Still, while alternating male and female names for storms may seem more equal, members of the public don’t necessarily views both kinds of storms equally. A 2014 study found that hurricanes named after women have happened to be deadlier than the ones named after men. The reason pinpointed by those researchers suggests that Bolton and her colleagues were right all along that it matters what you call a storm: people tended not to prepare as well for them, on the idea that storms named after women didn’t sound as aggressive.