In 1985, John Lewis conducted an interview for the Eyes On The Prize TV series documenting the history of the civil rights movement, detailing some of his memories from the iconic march from Selma to Montgomery, as well as reflecting on the power of the movement.

And even now, more than 30 years since that interview was recorded, many of Lewis’ words still ring painfully true, particularly as he spoke about our struggle being one of “many lifetimes” not just of “one day” or a “few weeks.”

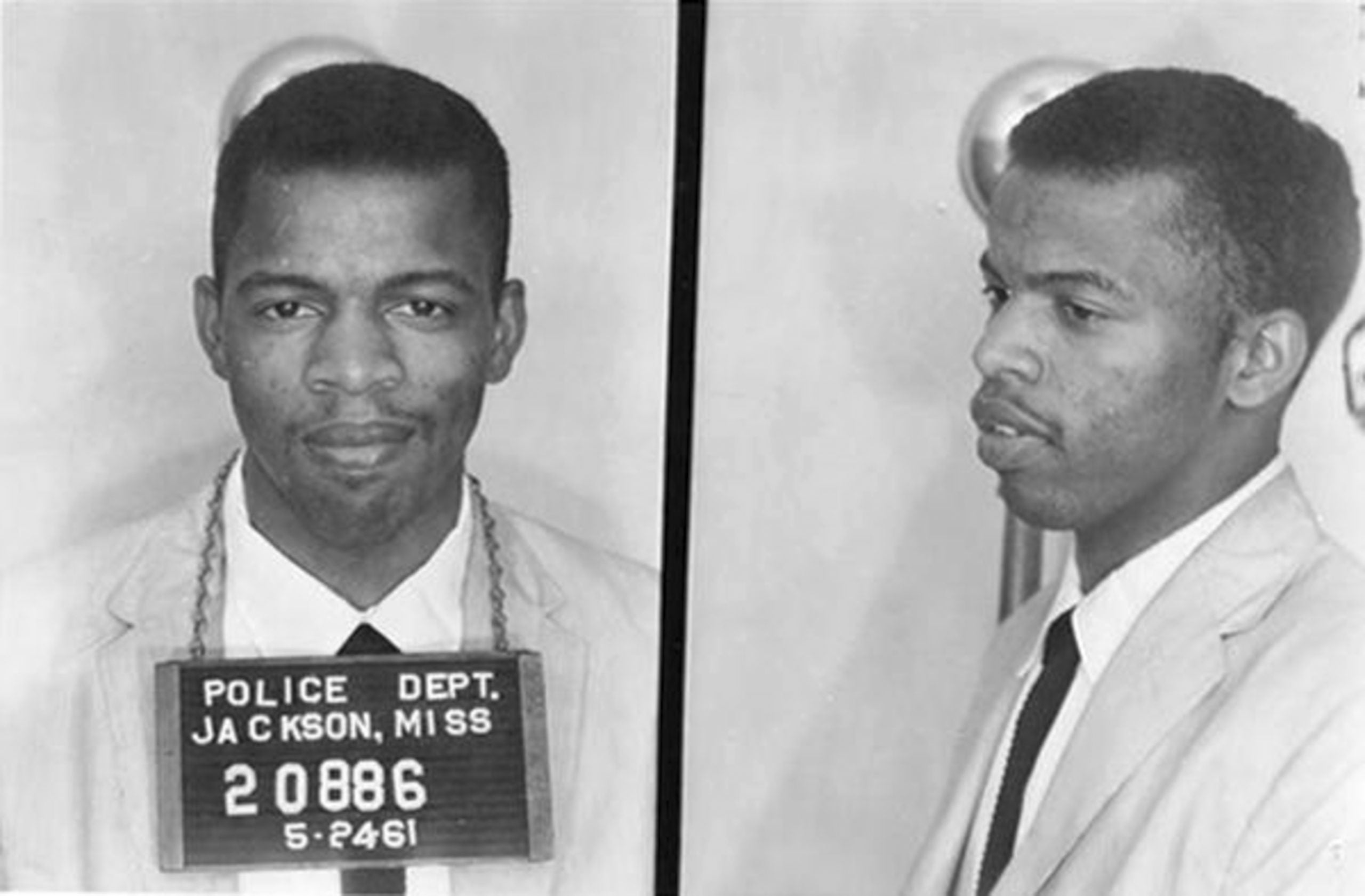

“The Movement instilled in me that sense of hope, that sense of faith, that sense of optimism. It doesn’t matter really how many bombings, how many beatings, or how many jailings, and I did go to jail during that period, forty times, but you had to have that sense of faith, that sense of hope that you could overcome, you could make this society something different, something better,” Lewis told interviewers when asked where his optimism came from. “I came to the conclusion that our struggle is not one that lasts for one day, one week or a few months or a few years, but it’s a struggle of a lifetime, of many lifetimes, if that’s what it takes to build the beloved community, the open society.”

But even knowing this, and even given the fact that Lewis was brutally beaten by white police officers, to the point where his skull was fractured, on the march from Selma to Montgomery, he spoke of Selma fondly, calling it “one of the finest hours in the history of the civil rights movement.”

“In Selma, we had a response from the American people. The days after Bloody Sunday, there was demonstration, nonviolent protests in more than eighty major cities in America. People didn’t like what they saw happening there. There was a sense that we had to do something that we had to do it now,” Lewis recalled. “We literally, in my estimation, wrote the Voting Rights Act with our blood and with our feet, on the streets of Selma, Alabama and the high–and Highway 80 between Selma and Montgomery. “

When thinking of the Movement, Lewis acknowledged the influence that the Black church had on the Movement at the time, calling the Movement “almost like a religious phenomenon,” and pointing out that many of the icons that we think of nowadays came directly from the church itself.

“It was this sense that what we were doing was in keeping with our faith, with our religious beliefs. The philosophy, the discipline of nonviolence, the whole idea of love, the beloved community, an open society. And Martin Luther King Jr. preached and talked a great deal about redeeming the very soul of America,” Lewis emphasized. “We were not out to, to destroy, but, but to redeem, to save, to preserve the very best in America and to call upon the very best in all of us to respond.”

And that spirituality, through songs and prayer helped activists through the darker times when they were arrested and isolated, Lewis revealed.

In the end, despite the struggles, and despite the fact that he was beaten on that bridge, and despite the incredible violence that protesters met at the time, Lewis noted that there just comes a time when in spite of everything, “you keep your eyes on the prize.”

“I think it’s very much in keeping with the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence, that in spite of the fears or the misgiving or the reservations you may have, you tend to lose that sense of fear, and you keep your eyes on the prize, and you keep moving, toward the goal,” he said.