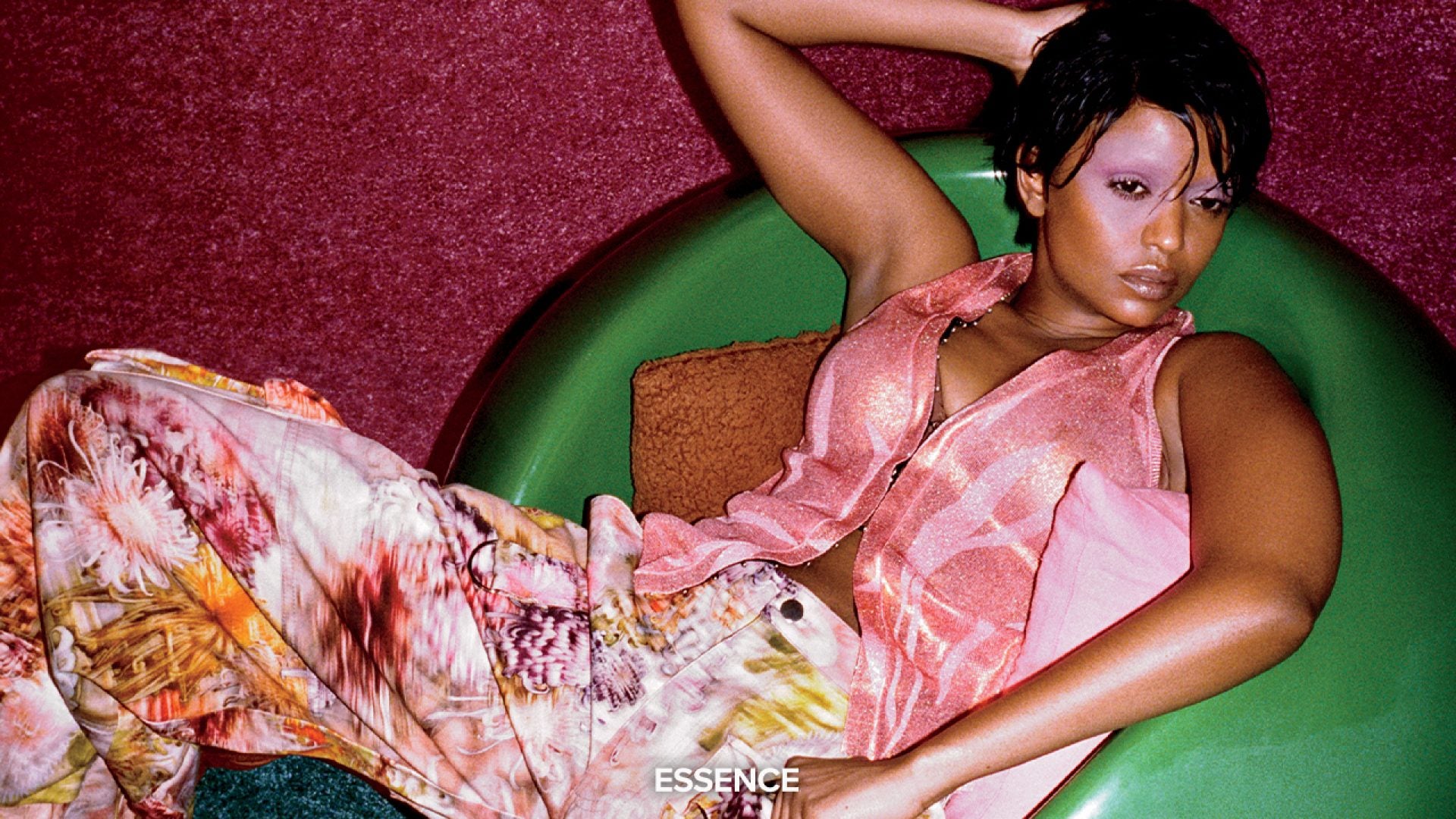

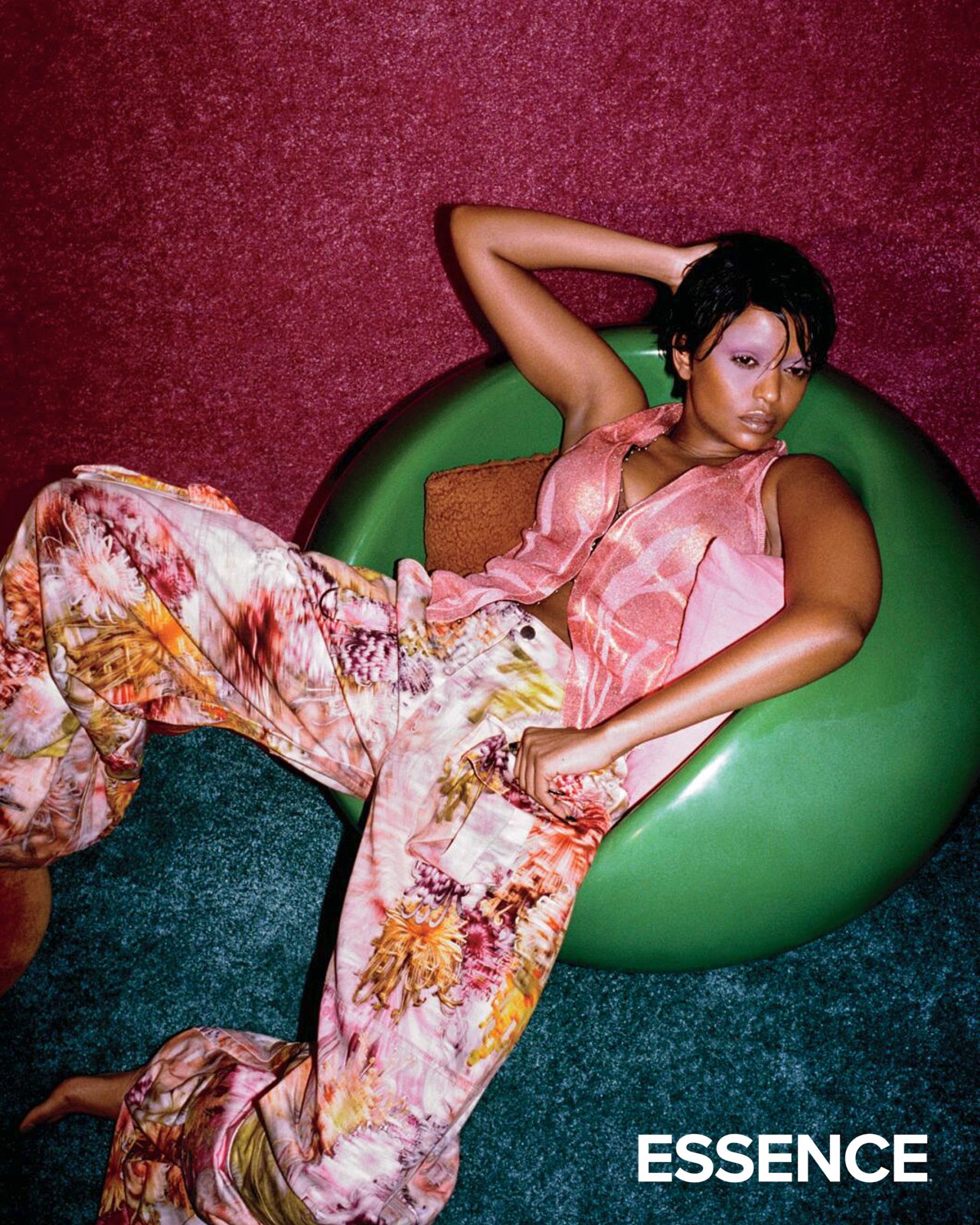

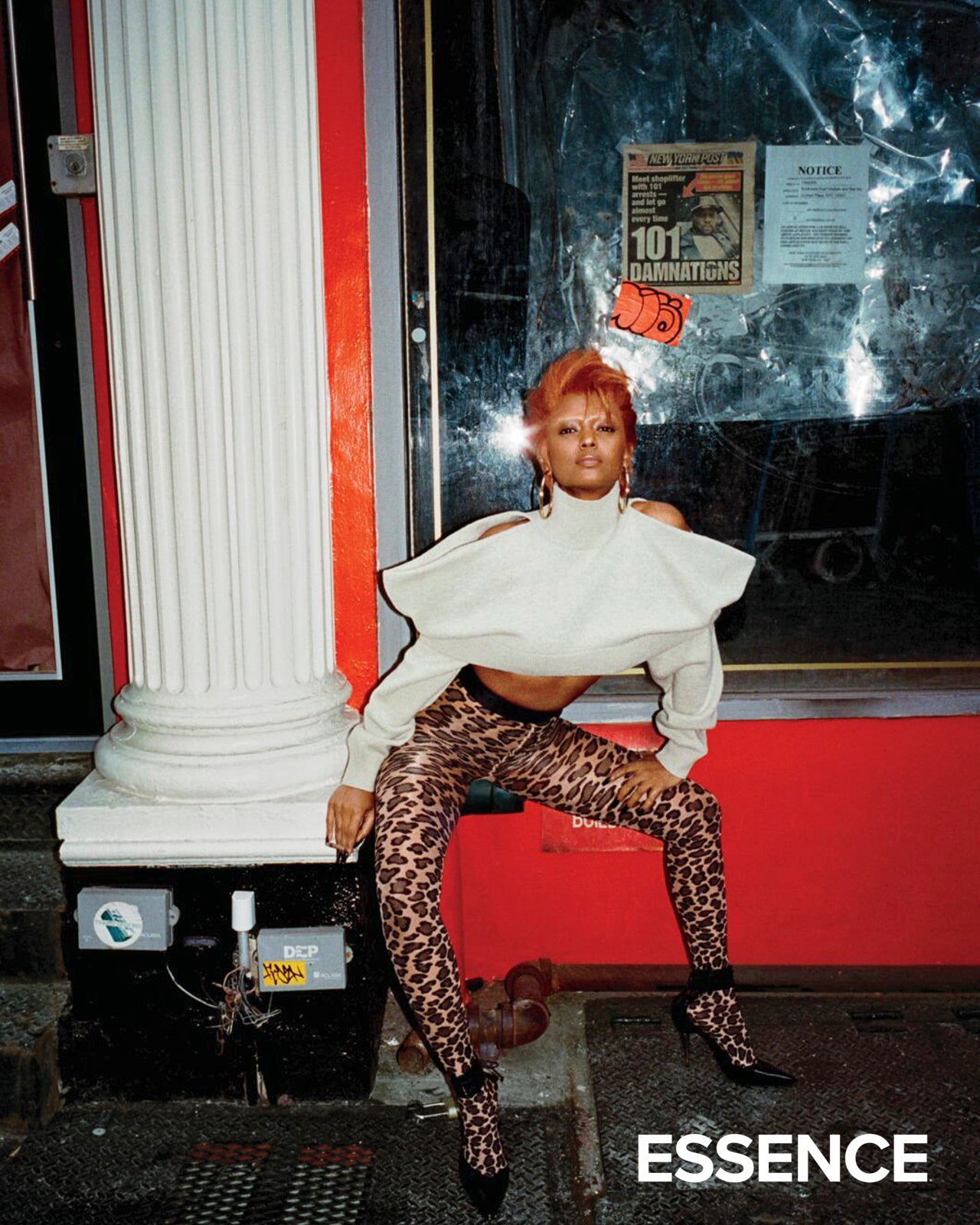

Photography by Eric Johnson, Styling by Corey Stokes

As Kelela got ready to shoot the music video for her latest album, Raven, she had a dilemma. The “LMK” performer had cut her hair, changing the look that she had rocked since the start of her mainstream career. That look was what supporters knew her for: locs cropped to graze her shoulders, flipped to her right, revealing a shaved head on the other side. All of it was now sculpted down into a buzz cut, revealing the full crown of her head. And she wanted to bring everyone with her in the music video for “Washed Away”—from dreadlocks to close-cut.

“What’s the way? I don’t even know,” Kelela said, trying to explain her thought process over the phone on a late January night in London. Her creative director, Mischa Notcutt, had an idea: Cut to the video, in which she wears a leather dreadlock hairpiece—thick, slightly worn, matte-black tubes emulating her signature style. As the video progresses, against a backdrop of clay-colored mountains and dark waters in her homeland of Ethiopia, she slowly slides the wig off with both hands to reveal a shaved head. She appears focused and intense, but her shoulders are relaxed. It’s a dramatic moment. The seriousness might lead you to think the wig was a high-brow artistic performance—a nod to Kelela’s growth over the past five years, since the 2017 release of her debut album, Take Me Apart. It was not.

“It’s a gag,” Kelela states now. “Mischa was like, ‘Do you want to do this gag or no?’ And I was like, ‘Absolutely trying to do the gag.’ ” Her choice is a reminder that some of the most fruitful ideas are birthed at the intersection of comedy, collaboration and resilience. “What I love is that there is so much humor. But people have to step back a little bit to see it, because I think that my sh-t does come off serious.”

If you need a way to categorize her, Kelela Mizanekristos is an R&B artist. The 39-year-old is also a master merger of genres rooted in Black music, such as house, electronic and their subgenres. She will tell you her music is for everybody. And crafting songs that can be felt unmistakably by Black femmes is a specific part of her intention. You can hear her songs on the club scene, as DJs bump house music, as well as inside the private sanctums of those craving vulnerability in a cruel world.

She grew up in Washington, D.C., a second-generation Ethiopian-American whose parents were politically active, fighting for their rights as immigrant students in America. In 2013, after moving to Los Angeles at 28 years old, she released her mixtape “Cut 4 Me”; an EP, “Hallucinogen,” followed in 2015. She also did a host of remixes with her peers, such as Kaytranada and LSDXOXO, who are both producers on Raven.

More recently, Kelela has emerged as a leading musician in the realm of alt R&B, both as a Black, queer solo artist and as a member of the global world of dance music. Her evolution is a reminder that while the music industry venerates youth in the club scene, people who live it know it is multi-generational.

“In Raven, I wanted to survey a lot of different subgenres of dance music,” Kelela says. She explains that dance music has hierarchies; at any given moment, one subgenre holds more weight or popularity, yet “they all originate from Black hands, and that’s my point. So I really tried to create smooth transitions, to aid the discovery of new music and new sound.”

Her song “Closure” holds a deep, sultry bass through the majority of a track—but that slinky, ching-y four count makes it taste like metal. Then, artist Rahrah Gabor emerges with a rap verse (“What the lick read?”) and the song transitions into a jungle breakbeat—a sped-up drum solo typical of ’60s or ’70s funk or R&B songs. In the late ’70s, DJs would merge drum solos to create this breakbeat. There are various versions of the sound used across genres of music today. “It’s me trying to show you how these things are related,” Kelela says. “It’s me saying, ‘This goes perfectly into this. If you get this, you can get this.’ And I just keep doing that.”

Kelela wrote each song on her album, with additional credits by painter Janiva Ellis and fellow artists Junglepussy, Asmara, Shygirl and LSDXOXO. “I would say that this record feels different in the way it draws its boundaries,” she says. “So it’s leading with love and vulnerability, but also it’s saying, ‘What we not going to do today is this,’ and it’s articulating a limit. Because I think there’s a way, that there’s devotion and then there’s an unhealthy other thing. On this record, I think I’m trying to articulate the distinction.”

Thirteen of the 15 songs on Raven were recorded in a six-day span in January 2020, before any of us in the U.S. had a true grasp of what was to come. COVID-19, lockdown, and the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Tony McDade were the elements of a subsequent uprising. “I initially thought it was just going to be a really quick-turnaround type project,” Kelela says. “Just going to not think too hard, first idea, best idea. Just really go for things from an instinctive place and not edit too much. So that was my goal, to use the process of making a record to affirm myself, and affirm my process and how I do it.” Another song, “Raven,” was added in February of that year. “Fooley” was the last song recorded. Ultimately, the wait for Kelela’s album was less the product of a hiatus and more of an aligning with the times.

One of her concerns was that people might interpret Raven as a “pandemic album,” one for which she did a lot of thinking as a result of global occurrences. “But this is how I’ve been feeling the whole time,” she explains. “And I knew before the pandemic that I wanted to get into that.”

In doing so, Kelela created a piece of work to meet this moment and propel listeners forward. “Part of that time was not just auditing everybody else but auditing myself, checking in with myself, and being like, Okay, so what are your values?” she says. “What do you want this to reflect? Where are the places that it doesn’t feel good? And just trying to get my decision-making even more in alignment with my values.” These questions required Kelela to get clear on this through her own continued studies during 2020, which included the individual audit—personally and professionally. That’s one thing about Kelela. She is focused on her own growth as a Black artist, versus fixating on the moral progression of White people.

“Professionally, I was thinking about my place in this realm of music, the power and the access that I have, the responsibility in that, and also the ways that I’m marginalized—just really being clear with everybody that I work with about what’s actually happening, the ways that capitalism and colorism intersect when it comes to Black femmes in the music business, period,” she says.

The Billboard Top 100 between 2012 and 2021 offers a snapshot of what Kelela is talking about. According to USC’s fifth-annual report, In the Recording Studio, women are more likely to appear credited as songwriters in electronic music (20.5 percent) than for pop songs, (19.1 percent). Women songwriters are significantly less likely to work on hip-hop (6.4 percent) and R&B songs (9.4 percent). Yet the ratio of men to women artists who topped charts in this latter genre was only 3.6 to 1—suggesting an environment where the gaze and taste of White men steer what’s worth investing in. This is what Kelela is referencing when she talks about the nuance and crassness she and other artists face. “No one’s able to create security without approval,” she notes. “And that’s just the reality.”

The question for Kelela then becomes: How has she been able to do it? How has she risen as one of the more visible Black women signed to an indie record label who’s making Black music? “Other Black femmes in my life,” she explains simply. “There are a lot of other things that contribute to that, but my core safety, and just the affirmation I’m getting to really deal with everything on the daily—that’s coming from my inner circle of friends.”

Production credits: Hair: Kabuto Okuzawa at Walter Schupfer Management. Makeup: Raisa Flowers using MAC Cosmetics, at E.D.M.A. Nails: Leanne Woodley using SHE NAILS IT Hydration, at She Likes Cutie. Set Design: And Or Forever. Set Design Assistant: Shane Smith. Fashion Assistant: Timothy Garcia. Styling Interns: Alec Malin, Maraida Jackson. Photography Assistants: Aidan Tan, Tatum Mangus. Retouching: One Hundred Berlin. Production: The Morrison Group.