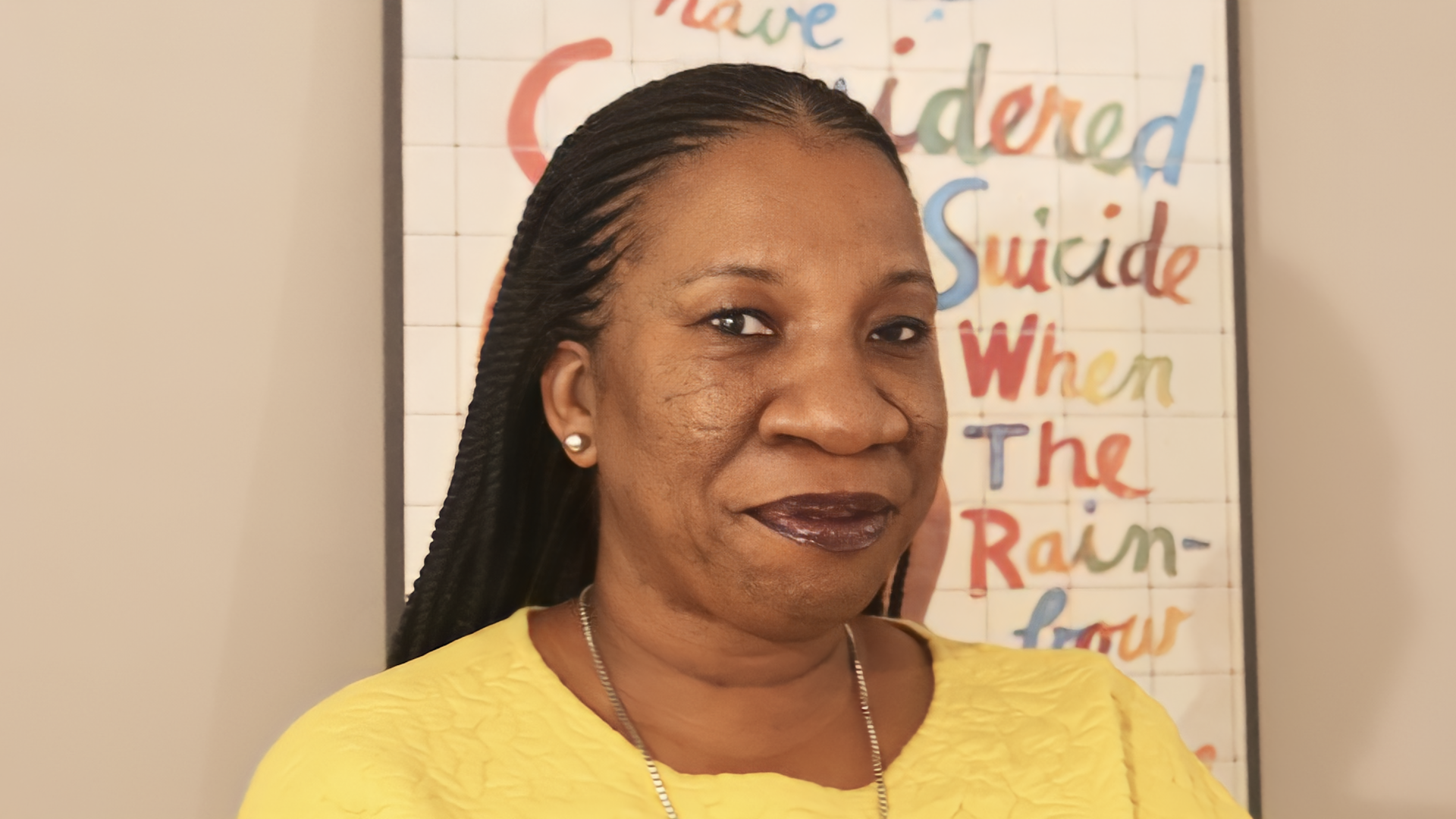

Tarana Burke’s MeToo was never about misandry. MeToo is a call, and a space, for Black survivors of sexual violence to be surrounded by love. Exactly five years after the movement gained steam, Burke isn’t afraid to weigh in on the conflation of MeToo and “cancel culture.”

“Every time you hear somebody equate MeToo with cancel culture, we should be voicing opposition to that,” Burke, 49, says to ESSENCE. “[T]hat is actually not what this is about. Because first of all, what that does is it reduces people’s disclosure of sexual violence. It says that it’s more about the people who cause harm and their safety and protection than it is about the people who’ve been harmed.”

Burke, an activist and organizer, launched MeToo in 2006, using the phrase on MySpace as an expression of solidarity with survivors. Her work continues the legacy of anti-rape activism, a lineage that includes Rosa Parks, who investigated the brutal 1944 rape of Recy Taylor on behalf of the NAACP. Parks, like Burke, had her own experience with sexual abuse, which colored her work and encouraged her to advocate for others.

Burke entered international conversations over ten years after the beginning of MeToo, when film producer Harvey Weinstein was accused of sexual abuse by dozens of women in October 2017. Actress Alyssa Milano then brought the language to Twitter, sharing it with her audience of millions, writing, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet,” attaching a text-based photo with a similar call to action. Milano also identified herself as a victim of sexual misconduct in the replies.

The place of the celebrity in activism, particularly in this movement, is not one that Burke deems completely unnecessary. With that, she’s critical of celebrity obsession and its ability to distract. “I think that there’s so much emphasis on celebrity particularly in this work and this moment because of how it was introduced to the public,” she shares. “So because of that, we are constantly dogged by and judged by the movements and inclinations of celebrity and connected to pop culture and what happens inside of that space. It’s a wildly unpredictable space and it’s not the average person’s reality.” She’s clear about not cropping out famous survivors and diminishing their need to heal. At the same time, Burke’s seen some disturbing responses to high-profile people being accused of assault.

She demonstrates this point by mentioning R&B performer R. Kelly, who a Chicago judge recently sentenced to 30 years in prison following charges of racketeering and sexual exploitation of children. Kelly’s music became popular during the 1990s, and not soon after, word spread about his inappropriate relationship (including an annulled marriage) with 15-year-old singer Aaliyah. The allegations of sex abuse continued throughout his career, meanwhile his music continued to ooze out of speakers. (Even today, there are multiple songs of his that’ve gone viral on TikTok.) When the 2018 dream hampton documentary Surviving R. Kelly was released, Kelly’s devout following began to view the women’s stories as a calculated takedown. Thinking media and survivors are unjustly maiming a public figure’s legacy is a common belief system, and it’s a dangerous one that decenters survivors.

Burke is open about some members of the Black community not feeling included in MeToo, mainly because of how it became a phenomenon and the names associated with it. “A lot of people weren’t invested in the MeToo movement. They felt like it wasn’t for us. It was what was going on with the white women in Hollywood and stuff,” she says. “Then they heard R. Kelly’s name. The minute R. Kelly’s name was introduced, it was like, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa. Wait a minute. Why y’all trying to take down that Black man?’”

“We as a community have to say [that] there are times when there are people inside of our community that don’t mean us any good,” she says.

People’s fierce loyalty to wealthy, well-known, but still strangers, concerns her. We agree that some are bound to harm-doers and refuse to cut the emotional or psychological cord. “They don’t care about your material lives, and yet you are dying on this vine,” she says.

During our Zoom conversation, I mention there’s still an air of taboo regarding Black women opening up about being violenced. The shame and potential of being misunderstood haunts survivors before they open up about their experiences. She has faith that Gen Z, a generation defined by their fearlessness, may help alleviate those concerns once and for all. We know better than to put too much stock in one collective, but still, there’s hope.

“I think that they’re going to push and they’re going to demand that we talk about sexual violence differently and that we show up for each other in community differently because they’re not silent. They refuse to be silent about anything, which is good.”

Having an unrelenting group of supporters could only help MeToo’s mission and support their work, which is far from done. The organization is gearing up to share a breakdown of their vision, honoring the strides they’ve taken thus far, while looking to the future. “We plan to spend this whole year, not just this week, commemorating but also working and bringing visibility to this movement,” Burke tells us. She also acknowledges their explosive, digital origin story, before revealing they’re looking to do more in-person activations.

“2017 into 2018 was a monumental year. We’re going to spend this whole next year doing what we call going beyond the hashtag,” she says. “We have a series of community events that we’ll be doing. Our first one is in Philadelphia on the 28th. Of course, we’ll continue to do our programs that we’ve been doing, including our web seminars, and web series.”

Her focus now, as it has been, is adjusting the thought patterns and dialogue about sexual violence and recognizing how it impacts lives. She views MeToo as a multi-pronged initiative prioritizing both healing and action, with an educational aspect, too. Burke wants to make people who may have previously felt alienated know that there’s a place for them in MeToo.

“We want to make it easier for people to feel connected. That’s our goal. That’s certainly this work,” she says.