Tuesday, Jan. 17 is the seventh annual National Day of Racial Healing, which is observed on the day after Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) and NBCUniversal News Group are hosting two town halls for the observance “to contemplate our shared values and create the blueprint together for #HowWeHeal from the effects of racism,” a statement reads. It is “an opportunity to bring ALL people together in their common humanity and inspire collective action to create a more just and equitable world.”

Last June, NBCUniversal News Group and WKKF partnered together in a yearlong “editorial collaboration to promote the dialogue around racial equity issues and help to advance racial healing.”

On Tuesday, in a culmination of this initiative, MSNBC and Noticias Telemundo are hosting town halls in front of a live studio audience from the iconic New Orleans landmark, Studio BE.

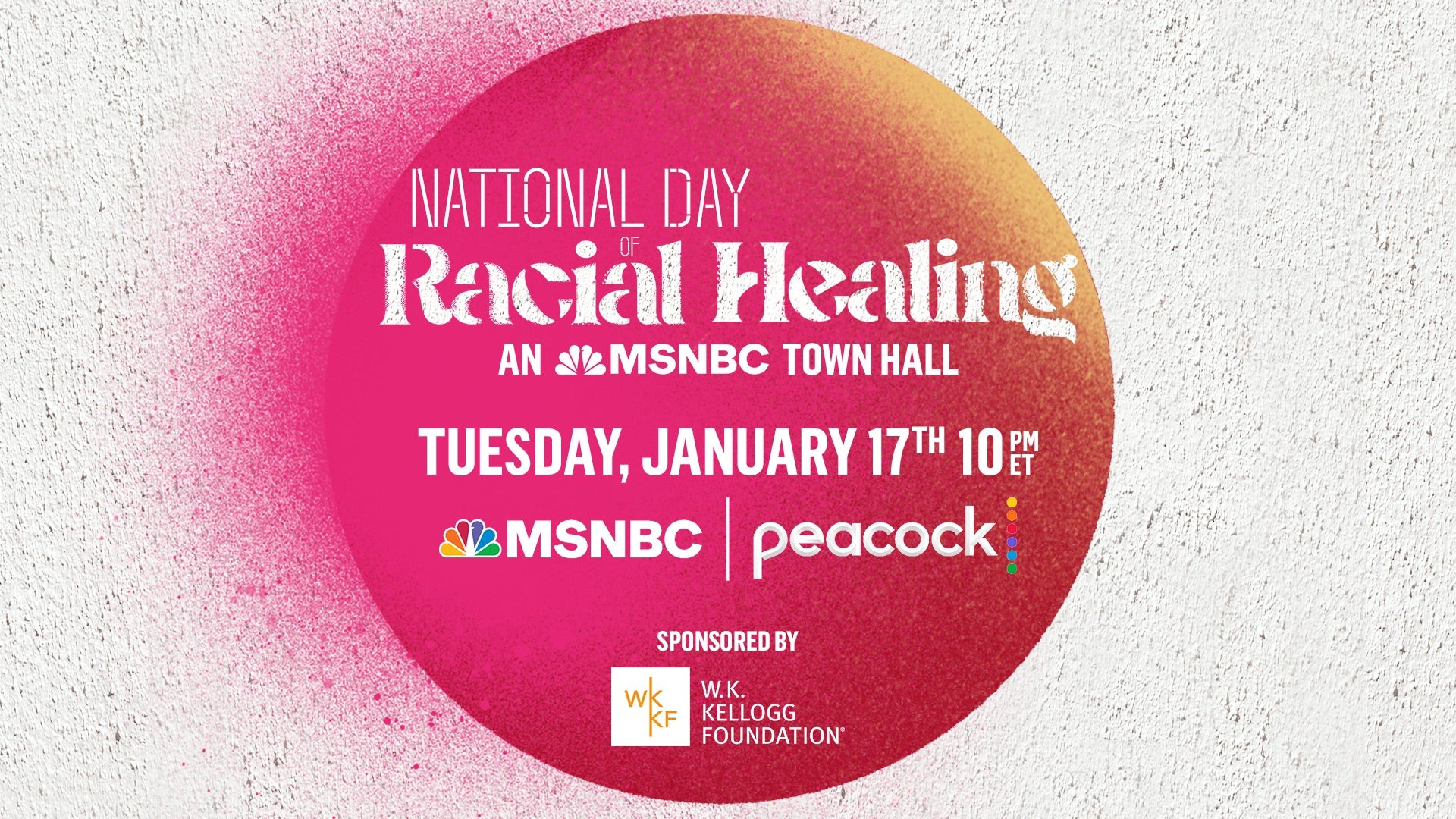

The National Day of Racial Healing: An MSNBC Town Hall will air at 10:00pm EST on Tuesday. Viewers can watch on the Peacock livestream or catch the town hall the day after via on-demand.

MSNBC’s Joy Reid, Chris Hayes and Trymaine Lee, will host the televised event. They will be joined by Minnijean Brown-Trickey, activist and member of the Little Rock Nine, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The New York Times Magazine and creator of the landmark 1619 Project, and White House Infrastructure Coordinator and former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, among others.

In advance of Tuesday, Reid, Hayes, and Lee spoke with ESSENCE about racial healing, the significance of this town hall, and what they hope viewers will walk away with after watching.

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

ESSENCE: What does racial healing mean to you?

Lee: In this moment, not unlike times in the past, I can’t help but think about Malcolm X and his words on progress. He talked about if you stab someone in the back, and the knife goes in nine inches, and you pull it out six [inches], that’s not progress. It’s not progress until you pull the knife out and start to heal the one thing that actually addresses the wrong that was caused.

When I think about racial healing, I think that it’s not just rectifying the systemic wrongs that have been done, but the material wrongs. There really needs to be a coming together, not just morally, but ethically, understanding the wrongs of the past, acknowledging those wrongs and beginning to find ways to move forward. In this post-George Floyd world [that] we’re in now, this present rise of all the -isms, all the anti-Blackness and antisemitism, in this moment especially, it’s important that we have these conversations about the wounds that still fester, especially when it comes to race.

Hayes: One of the things that I’ve come to think through after acquainting myself with the Kellogg Foundation’s work is that one of the ways you get people on board with the agenda, particularly folks who don’t view themselves as impacted, is through the kind of psychological and social work of racial healing, confronting this lived reality that certain people don’t have the privilege of and making it present and tangible in people’s lives. [And it must be done] in such a way that you move them psychologically to understand structural factors and forces and engage in the kind of work to address that.

Reid: It’s a complicated thing—truth and reconciliation. I think it means accepting the truth of the past and finding a way past it, in order to make the country whole.

When I think about racial healing, I think that it’s not just rectifying the systemic wrongs that have been done, but the material wrongs.

Trymaine Lee

ESSENCE: MLK Day, the National Day of Racial Healing, and Black History Month all fall on the heels of one another—how will the topics discussed at this town hall be different from the anecdotes and euphemisms typically espoused?

Reid: It must be different, because I think that the muppetification of Dr. King is one of the great tragedies of history, and when I say truth and reconciliation, I mean even the truth about Dr. King. This wasn’t a guy who only said ‘judg by the color of our skin and the content of our character’ and ‘I have a dream.’ They distilled him down to those two lines; but, the truth is for Dr. King, racial healing meant economic parity for the poor. It meant understanding that poverty is a choice that is being made to the detriment of Black people, brown people, and poor white people, and that racial healing meant allying those three groups of people to not fight each other, and to fight for better.

What I hope comes out of this conversation is that we talk not gauzily and in Hallmark card-style about how great it would be to be post racial but that we use the incredible resources that are going to be at the table. If this is to be successful, we need to talk about the work that needs to be done, and challenge people to do it, let people know that they can do it without feeling frightened or threatened. That’s one of the problems we’ve had in this country of late, is that people feel frightened and threatened about doing that work rather than hopeful about what it can bring.

Lee: I can’t say that it will be any different, but I think it’s a step in the right direction. When we talk in very simplistic terms about this idea of racial healing, I’m not sure America is in a position to actually heal racial wounds, but I think every effort made in that direction using this kind of language, gathering thinkers and doers and everyday people, continuing to have the conversations that might fuel some actual systemic change, is helpful.

It’s an easy out for a lot of people. With Black History Month coming up, we put together these kinds of events, town halls, and we just talk and talk and talk. It’s not enough, but it is a start, because there are a lot of places in this country where the conversation isn’t even being had. There’s legislation and politicians being fueled on the notion of silencing these conversations, let alone what’s being taught in school and education, and the truth about America. The way America has always presented itself and the way it’s actually moved and acted is contradicting itself. Even though it’s easy to dismiss these kinds of efforts, these are really important efforts because there are many institutions in this country and many people in power who don’t want these conversations to be had.

Hayes: I do think, yes, there’s a kind of sameness to this notion, some of the stuff that gets very causally corporatized around the [MLK] holiday is just at the first level, but it was a much deeper, more radical vision than service. The key is that this is a starting point and not the goal in and of itself, and so the point is that you have to have conversations as a means of moving people through that process of democratic persuasion, to get people to see the problem to better address it, and so I think that’s the key for how we dive into this town hall.

ESSENCE: What message do you hope for viewers to take away from watching this town hall?

Hayes: That this is part of the iterative process that you bring people along to understand the reality and the fundamental injustice of the existence, the durability, and the incredible robustness of racial supremacy and hierarchy in the United States, and that is a long project. It’s a project that accumulates over time and has a cumulative effect, but all of that is part of moving people along.

Reid: If I had one takeaway, it would be that a healed nation would actually be a more comfortable, more wonderful place for all of us. A nation where we could look at our past with honesty, but without rancorous emotion would be a better future for us. There are lots of countries that have done this, and they’ve had these internal confrontations, and they survived. They were able to confront the horrors of what happened, and in some cases, what their fathers and their grandfathers had done, and they were able to forgive themselves. It’s like learning to swim. I’m not a great lover of swimming, but I do know that the first step is to get in the water. You’re not going to learn to swim on the side of the pool. The first and, sometimes most frightening, step is to jump in.

Lee: This is another one of those cliches, but I think education is key, because in this country, we have always lived in these very segregated spaces. We’ve been these planets, oscillating in completely different worlds. When we are able to educate people about the truth about America, and race in this country and how it’s lived, and there’s so many people who really do remain ignorant, and again, intentionally so, sometimes blissfully so, but for people to walk away with a better understanding of their neighbor, of their fellow citizens, I think that’s actually a win because you do need empathy. This sounds soft and squishy, and we need hard material change in this country, but I think it really is important for people to feel each other, in very humane ways.

I hate using that word, humane, especially when it comes to us, like people have to humanize people. But sadly in this country, we still do have to humanize people and humanize our experiences. So, I hope folks walk away with perhaps a little more empathy. Hopefully, the conversation will be had, where people can drop their guard and not be afraid to make the mistakes. It is messy, this work of trying to right the wrongs of this country, and certainly the wrongs of racism, the explicit and implicit kind of racism that exist in this country. But hopefully folks will walk away a little better, armed and enthused to try to make change. Even if it’s just a handful of people, I think that’s a win.