At the birth of the Harlem Renaissance, New York City was teeming with Black creative energy. Artists like Duke Ellington, Fats Waller and Ethel Waters were regularly lighting up the ears and eyes of music hall-goers. Most of them were limited to only performing live since Black musicians had virtually no way to professionally record and distribute albums due to lack of access to high-brow music labels. That is, until Black Swan came around.

Harry Herbert Pace noticed that these incredible musical forces were overlooked by powerhouses like Columbia and Paramount Records. Recognizing the artists’ need for wrap-around support with marketing, production and overall management, in the spring of 1921, he created his own label Black Swan Records, the first of its kind for African Americans. For a time, he helped to cultivate a haven of thriving artists that could focus on their talent without the burden of dealing with the business of music.

Like Pace, Cam Kirk recognized a modern renaissance of Black talent. Only this time, nearly a century later, centered in Atlanta.

When he landed there for his freshman year at Morehouse in 2007, he said he felt the grounds buzz with energy.

“Atlanta was definitely the place to be if you wanted to make it as a creative,” Kirk remembers fondly.

A microcosm for Black music, Kirk quickly got involved in artist management and promotions while juggling his studies, but realized he couldn’t afford to outsource photography services. What happened next, in 2010 changed the trajectory of his career forever.

“I bought a camera and decided to shoot our content myself,” he shared with Essence. This skill came second-nature since his father built a successful career as a photographer and taught Kirk everything he knows. He said shooting his artists sparked his intersectional passion of music, entertainment and photography.

“It just was like a light bulb moment for me, and I didn’t know there were real jobs you could secure from behind the camera. I didn’t realize I could work with rappers and musicians, athletes and celebrities by just getting in these rooms as a photographer. Atlanta introduced me to that aspect of it. And that’s really where I kind of got my start.”

Leveraging the relationships he’d already cultivated as a manager and promoter, he became one of the premier photographers for notable artists like Young Thug, Mike Will Made It, Gunna, Megan Thee Stallion and Big Boi among others. He also shot campaigns for Facebook, Nike, AirBnb and Sprite to name a few.

After years of success, Kirk said he wanted to spread the wealth of knowledge he gained as an independent photographer for years.

“I knew I needed to take all the notoriety I’d earned and pour that into something a little bit more sustainable,” Kirk said. In 2017, he opened Cam Kirk Studios in Atlanta, what he describes as a home for other creatives.

“I wanted to offer them the opportunity to connect with like-minded professionals, swap resources, and learn from one another.”

The studio also allows for the artists to have free photography studio time to take their clients and shoot. They’re also able to rent equipment at no cost. A booming space, Kirk says they turn over about 500 appointments per month in the studio, but he wanted to take it a step further.

“The studio is really like a factory house for creatives and dope, talented individuals, but I was able to see where the flaws were in their growth journey. I then decided to formalize the blueprint I’d followed to build my own success as a freelance photographer, and make it available to others.

That’s when he said the idea for a “record label” for photographers came about.

“I want to be able to give that to other photographers that I truly believe in and help them blow their careers up,” Kirk said.

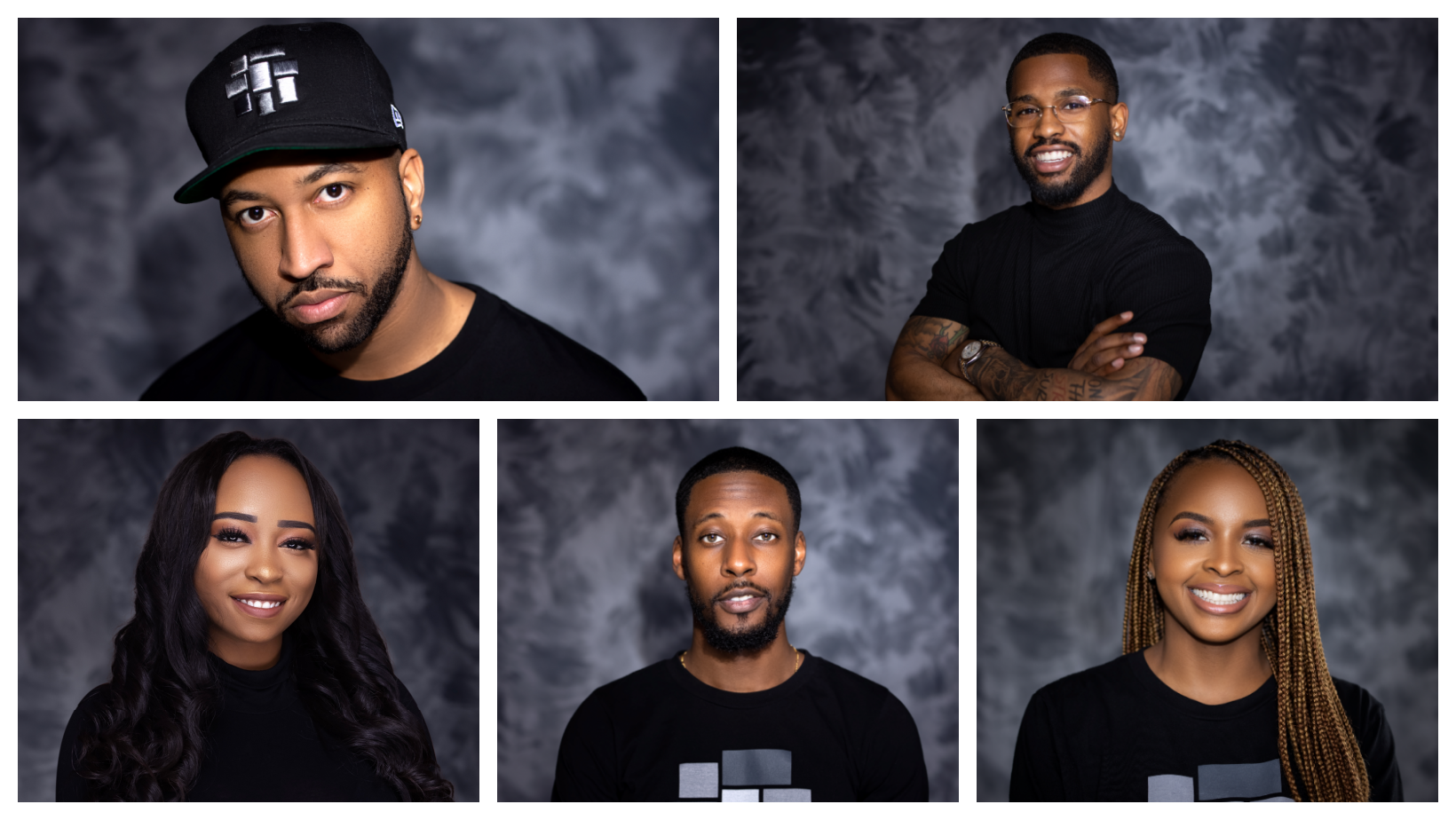

Alongside his long-time friends Aurielle Brooks, Shelly Andrews, John Rose and Kyle Bailey, Kirk launched The Collective Gallery.

“One of our main goals here at Collective Gallery is to give young diverse creatives the opportunity to work in the entertainment content space with some of the leading companies in the world,” said Rose, who is The Collective Gallery’s President. “Our impact rests in the support we provide to these young creatives, both monetarily and strategically.”

Kyle Bailey, who acts as the Director of Business Operations explains that The Collective Gallery shares the same structure as a major music label, even down to the A&R process. Although they have eight signed artists, the Collective Gallery also helps connect local unsigned freelancers with opportunities they know would be a good fit.

“We have an A&R based in New York that has helped us build a database of more than 1,000 creatives across the world that allows us to provide client solutions across many verticals. Hypothetically, if the NBA calls us and says, ‘hey, we need a videographer and photographer in New York to execute this shoot,’ we go into the database, ensure the photographer is vetted and place them with the opportunity.”

To date, Bailey said they’ve provided more than 400 jobs to creators outside of those that are signed to the label.

In addition to job creation, similarly to music label executives, The Collective Gallery said they work to create pathways for their artists to develop their own personal brand through upfront backing for marketing and production. They explained that that’s what sets them apart from creative agencies.

“Most agencies, not all, but most don’t necessarily invest financially into their clients’ dreams out the gate,” said Kirk. “We’re looking for talented artists, people that are great photographers that we feel can take their craft to the next level. And often, we do that by directly funding some of their ideas.”

Kirk explained that they funnel money into shoots, fund gallery exhibitions, front costly production fees for marketing materials like coffee table books among other services. He also explained that unlike predatory music label practices, they offer advances upon signing that the artists aren’t required to pay back.

“It’s not a 360-deal kind of situation at all,” Kirk explained. “We prioritize fairness and honestly, I treat everyone in the way I would’ve wanted to be treated as an up-and-coming photographer.”

The label’s general counsel and vice president, Aurielle Brooks explained that they take strides to protect their signees from all angles, especially legally.

“We also teach our artists,” Brooks said. “From the moment they’re about to sign a deal, we go through it with them line by line,” Brooks explained, who is an entertainment attorney by trade. “I’m used to working with artists who may not necessarily know, one, what they’re signing, and two, the legal aspects of the situation at hand.” She also said they provide free financial counsel upon signing as well.

Shelly Andrews, who heads up strategy and operations said the Collective Gallery is what she’d want music labels to run like.

“Being a part of Collective Gallery is what I imagine being a part of Bad Boy in the beginning was like,” Andrews said. We’re young, black, and eager to take on challenges. It’s a fun and innovative time and such a blessing to be able to feed into various industries.”

“It’s a really exciting time for Black creatives right now, and I’m just glad to be a part of it.”