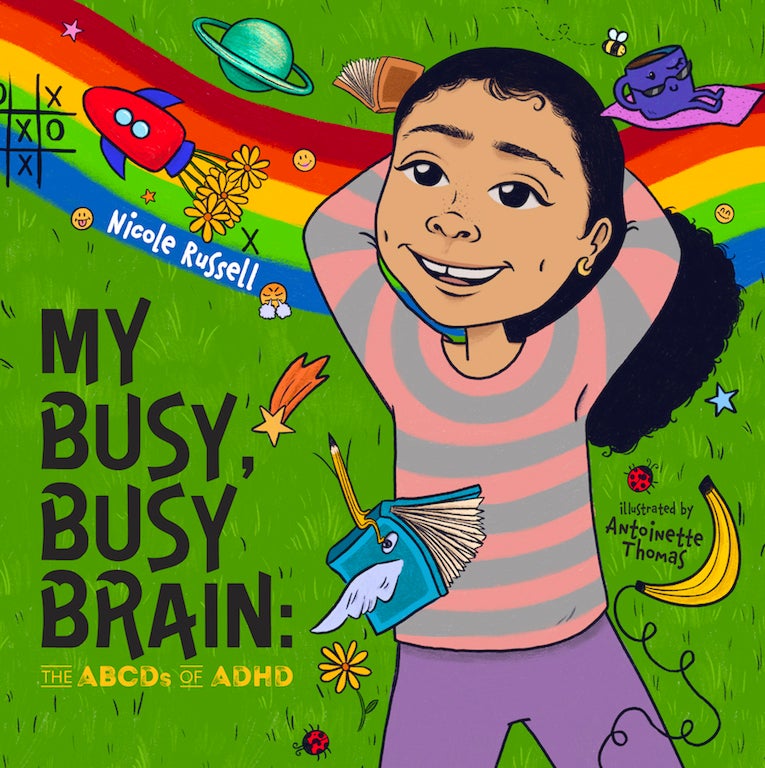

Parenting a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is demanding, and helping kids with ADHD understand themselves and their ADHD symptoms isn’t easy. Not only do kids have very little insight into their own behavior, but many don’t even realize that they’re daydreaming, acting impulsively, or moving around more than other kids. Not to mention, the many misconceptions about the diagnosis that are often spread among parents and other children. That’s why Nicole Russell wrote My Busy, Busy Brain: The ABCDs of ADHD — as a way to spark “aha” moments for kids and serve as excellent conversation starters for meaningful discussions between parents and kids.

Russell is a bestselling author and advocate for mental health and the well-being of children, as well as the co-founder and executive director of the Precious Dreams Foundation, a non-profit teaching children in foster care and homeless shelters to self-comfort globally. Since 2018 she has been inspiring and empowering children across the globe with Everything a Band-Aid Can’t Fix, which are a set of guidelines she created for understanding how to cope with feelings and experiences that aren’t always easy to share, and its companion journal Write Here & Tear Journal.

Not only are these age-appropriate books a great resource when it comes to helping kids with ADHD understand their own experiences, but also to help navigate their mental health journey. The books have inspired parents and teachers across the globe who’ve even adapted and recommended Russell’s books in classroom settings. And as resourceful each of her books are, more importantly, they are healing.

For ESSENCE, Russell chats about her latest book, being diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder as an adult and some of the biggest misconceptions.

What inspired you to write this book?

Saving girls like me. This book will empower children with ADHD to speak up for themselves.

Women and girls (specifically of color) are often overlooked when it comes to ADHD and when left untreated, a missed diagnosis can lead to academic failure, employment issues, and social and emotional challenges. I was overlooked as a child struggling with distractibility in the classroom and because I didn’t display behavioral issues, I didn’t get the attention and support I deserved, which led to years of frustration and low self-esteem.

I also wanted to educate children about neurodiversity, the idea that brain differences are normal, rather than deficits, and provide them with a positive example of someone with ADHD. Oftentimes, the disorder is associated with someone’s struggles. As the author, I wanted children to see my strengths, as a writer, as an empath and someone who is using their busy brain to help others. I hope more children and adults will find the courage to speak out about having ADHD and give the brain some credit for their accomplishments.

At what age were you diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder?

I received my diagnosis at 34. It took years for me to prioritize my health and just go for the evaluation. I figured I was getting by and didn’t need the professional opinion but I was wrong. Having the diagnosis has completely changed the way I practice self-care. I highly recommend anyone displaying consistent symptoms to go get tested, especially any parents of children with ADHD. We cannot fully know ourselves until we know the brain.

My Busy, Busy Brain: The ABCDs of ADHD is more than just an entertaining picture book; it is a valuable tool for children and families to understand the challenges of adolescent ADHD. Can you tell us about some of the resources that can be found in this and some of your other books?

All of my books provide coping strategies but most importantly they empower young people to do the work.

My Busy, Busy Brain provides ways in which children with busy brains can help themselves. There are tips to support hyperactivity as well as distractibility in and out of the classroom. I also aimed to normalize the different ways in which children can cope with their symptoms. There’s no one size fits all with ADHD. Some children need medication and some parents prefer natural remedies depending on the intensity of the disorder. There’s no right or wrong.

The book also offers a level of diversity that’s been surprising for many. I worked closely with the illustrator, Antoinette Thomas to ensure children would see themselves in the challenges of children that looked just like them.

Do you ever hear from young readers who tell you about their own difficulties and why your books help them?

Yes! My first book Everything a Band-Aid Can’t Fix is a self-help book for teenagers that has inspired breakthroughs in the classroom, at the therapist’s office and in the home. I’ve heard stories of parents reading the book along with their teens and finding the courage to uncover past traumas and family issues. I’ve had teens who don’t enjoy reading tell me that the book is addicting and they use it as a manual.

The book was initially rejected by agents and naysayers who believed “teens don’t need or buy self-help books” and now during the pandemic it’s become my biggest selling title. The feedback has been heart filling and young people are no longer waiting until their 20’s to learn self-care. Most teens aren’t crying out for support, they’re getting online to find resources to help themselves now.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about ADHD?

One myth is that children with ADHD aren’t smart. It’s purely ignorant to believe if a child is performing well academically they can’t have ADHD. ADHD is not a learning disability. I’m a returning college student with a 4.0 GPA and I have ADHD.

Another myth is that people with ADHD can’t complete tasks. We can. In fact, we can hyperfocus and multitask really well on anything that keeps our interest. Hyperactivity and impulsivity can be used as superpowers when it comes to entrepreneurship and creative projects.

The biggest myth is that boys have it more than girls. But girls that are overlooked don’t test for ADHD. Many girls go unnoticed because conversations about distractibility and ADHD aren’t common in schools and at home. We can narrow the gender gap in ADHD diagnoses if we normalize discussions around brain health and raise children to be self-advocates.