There were a lot of princesses in need of rescue in the fairytale worlds of our youth—so many damsels in distress, spellbound, and defenseless. But, lucky for them, there were legions of dragon-slaying, tower-climbing knights in shining armor whose kisses were the spell-breaking antidote and the keys to happily ever afters.

At the heart of these narratives are two apparent messages: Boys are brave, invulnerable warriors, there to save the day, and girls are helpless damsels waiting to be rescued.

While we can’t reverse the tropes that shaped our childhood imaginations or invoice their authors for the cost of therapy—there’s good news to be had. Thanks to a diverse new cannon of storybooks, today’s parents have many options to help shape the budding imaginations of the next generation.

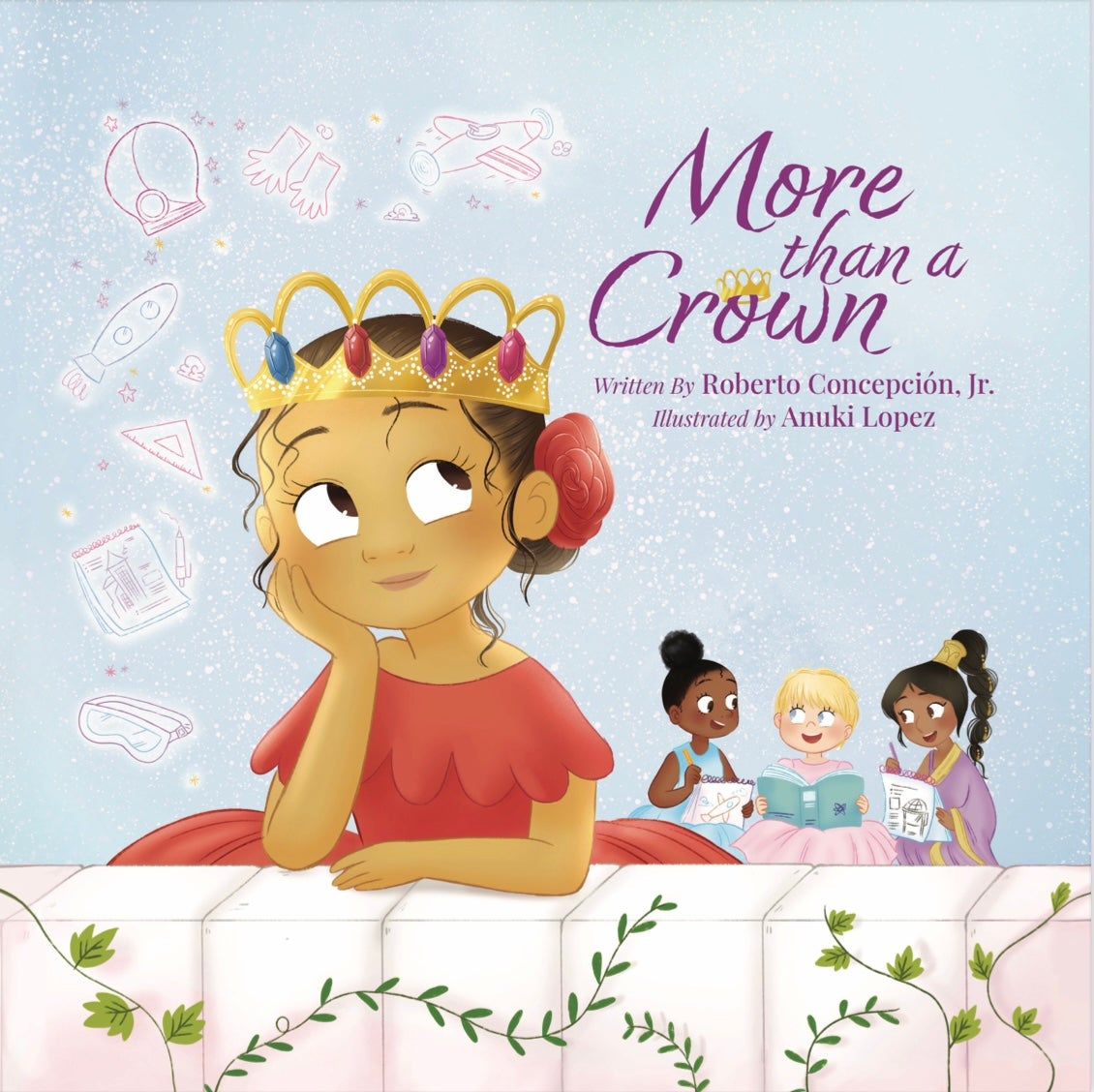

Roberto Concepción, Jr. is among the new authors diversifying the genre. His debut book, More Than A Crown, hit shelves on April 18th. The fiction, illustrated by Anuki Lopez, opens with Princess Amina brimming with excitement in anticipation for her royal tea party; Enter four princesses all regally dressed in their traditional cultural attire—a sari, a dara’a, a pink ruffle petticoat, and Amina’s bomba dress flow and flitter as the friends run, jumping and playing about the palace. The classic tale of royal rebellion follows the four brave princesses as they challenge tradition, defy expectations, and dare to imagine changing the world. In the beautifully illustrated storybook, readers will delight in discovering princesses are strong, smart, ambitious, and brave—more than maidens in peril.

I spoke with Concepción, a corporate attorney and self-identified Puerto Rican, gay, single dad. We discussed what inspired More Than A Crown, why it was important to challenge traditional tropes, and how his personal experiences and identity influenced the story.

Roberto, as the “creative Auntie” to bunches of littles, I’ve read dozens of children’s books. More Than A Crown is an instant favorite. What inspired you to write a story that challenges the traditional princess trope?

Thank you for saying that. You know, I started this book with one audience in mind, my daughter, Amina, and it’s just kind of turned into this really beautiful project. As a dad, I know it’s my responsibility to create an environment where she feels loved, where she feels valued, and empowered. So, when she was born, I asked myself, “What can I do to empower her, not just as a child, but specifically as a young girl of color?” And while children share many of the same experiences, being a young person of color is a different experience. And so, this book was about having Amina and other girls of color be able to visually see themselves finding their voice, following their dreams, and changing the world.

That message comes across effectively but subtly. How were you able to convey the message of independence and empowerment without being the least bit heavy handed?

It’s interesting you noticed that. It’s there but it’s intentionally subtle. For example, if you notice the affirmation on the dedication page, you’ll see that the word “beautiful” is in there, but it was not the first thing. Just because I think girls are taught that their beauty is one of the more important, if not thee most important, thing about them. And I want my daughter Amina to know that she is beautiful, but that’s only one trait she possesses. I want her to feel empowered and know that she is smart and strong—a whole human being.

The princesses come from all sorts of different backgrounds, but the book also depicts diverse family structures. There’s a single-parent family, a same-sex family, and a blended multi-racial family, all represented. How did your experiences as a Puerto Rican, gay, single dad influence these choices, and your writing overall?

While I do inhabit those marginalized identities, I also recognize my privilege. I have a thriving career, you know, I live in New York City—so regardless of my identity, I’m still in a position of privilege. And listen, privilege is obviously very relative, but the fact that I have been “out” throughout my entire career, and I’ve been able to live as an “out” gay man, an “out” gay Latino man, and now an “out” gay Latino man that is a single father—it’s a privilege I recognize not everyone has. And so, I know that it matters for folks who don’t have those freedoms to see themselves represented. So, I think it’s essential to have diverse stories out there, depicting diverse families.

On that point, how important is it for children’s literature to have diverse authors, and how does your book contribute to that?

It’s a good question. You know, we live in a time where, even though there are more diverse children’s books than in prior years, the number of authors of marginalized identities has not kept pace. For example, I came across a study that showed Black, Latinx, and American Indian authors combined wrote just 7% of the new children’s books published in 2017. In addition, less than 2% of children’s books had significant LGBTQ-plus content and were written by LGBTQ-plus authors. So, having diverse representation in the genre is essential. I want this book to be a step in ensuring our stories are told, and our voices are heard.

It’s interesting because we’re in such a divisive era where so much of our literature is targeted. Books are being banned, Black history is being shunned, and LGBTQ+ stories are being silenced. What are your thoughts on the cultural climate you’re releasing this book into?

Look, I think, whether it’s critical race theory or the banning of books, there seems to be a push for a divisive “us vs. them” kind of othering. It’s intentional, I think. And now, more than ever, we need to continue to push back against the fallacies that are being created, to find the similarities, and to celebrate our differences frankly. The fact that we’re seeing this pushback reflects the progress and contributions our communities have made. We have to keep speaking up and putting our stories out there.

Responses are edited for conciseness and clarity.