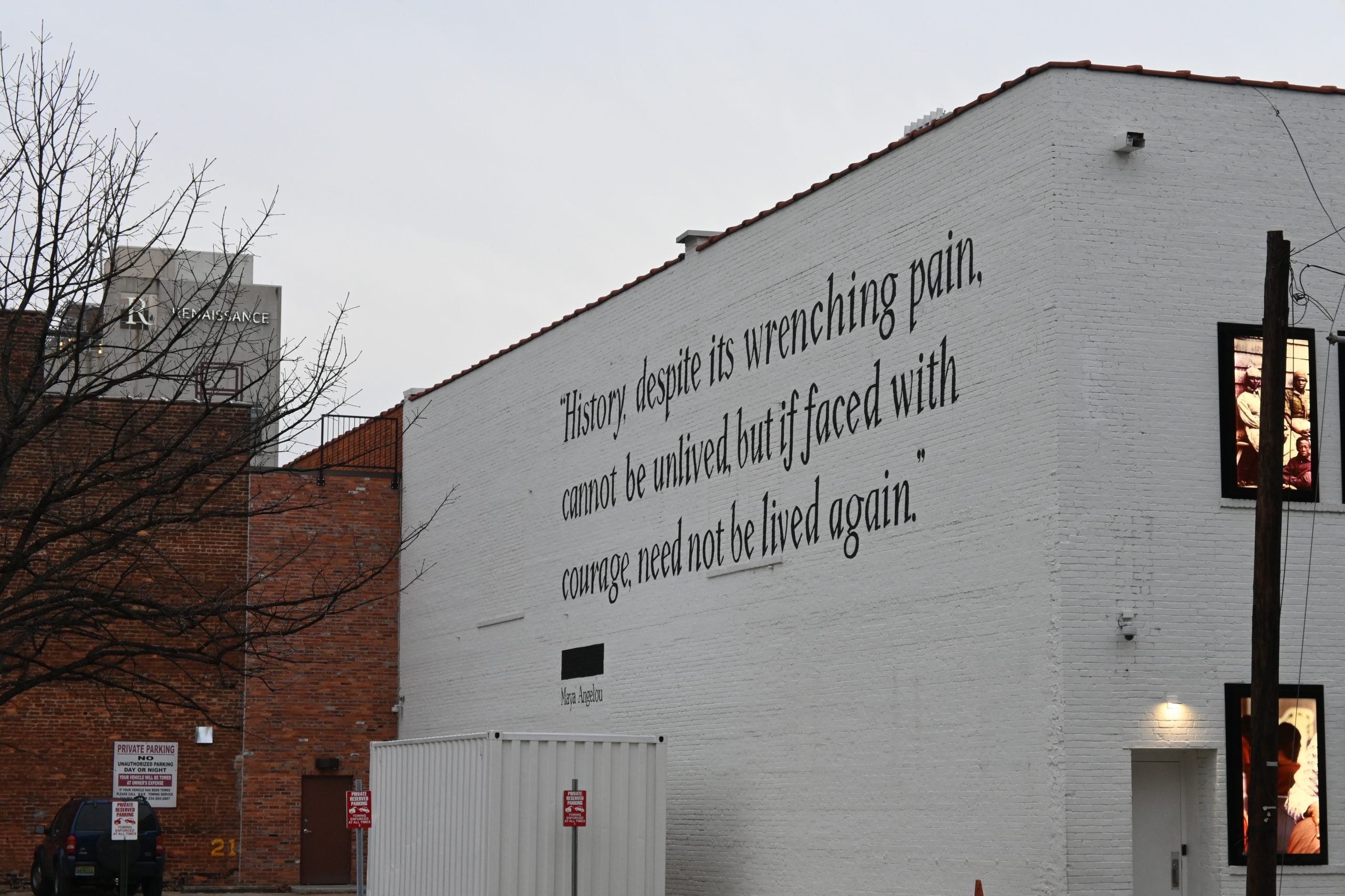

“History, despite its wrenching pain cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage need not be lived again.”

I spotted the reflection-inducing words by the late Maya Angelou just moments before entering the lobby of Montgomery’s Springhill Suites Hotel. They adorned a nondescript wall at the corner of Coosa and Bibb, which was steps outside of my temporary retreat. Now I’ve always been more Manhattan than Montgomery, slightly more Malcolm than Martin, with more northeastern edge than southern charm. But there I was, just days before the Christmas holiday, excited, and yet nervous, to be in what I considered the epicenter of Black history.

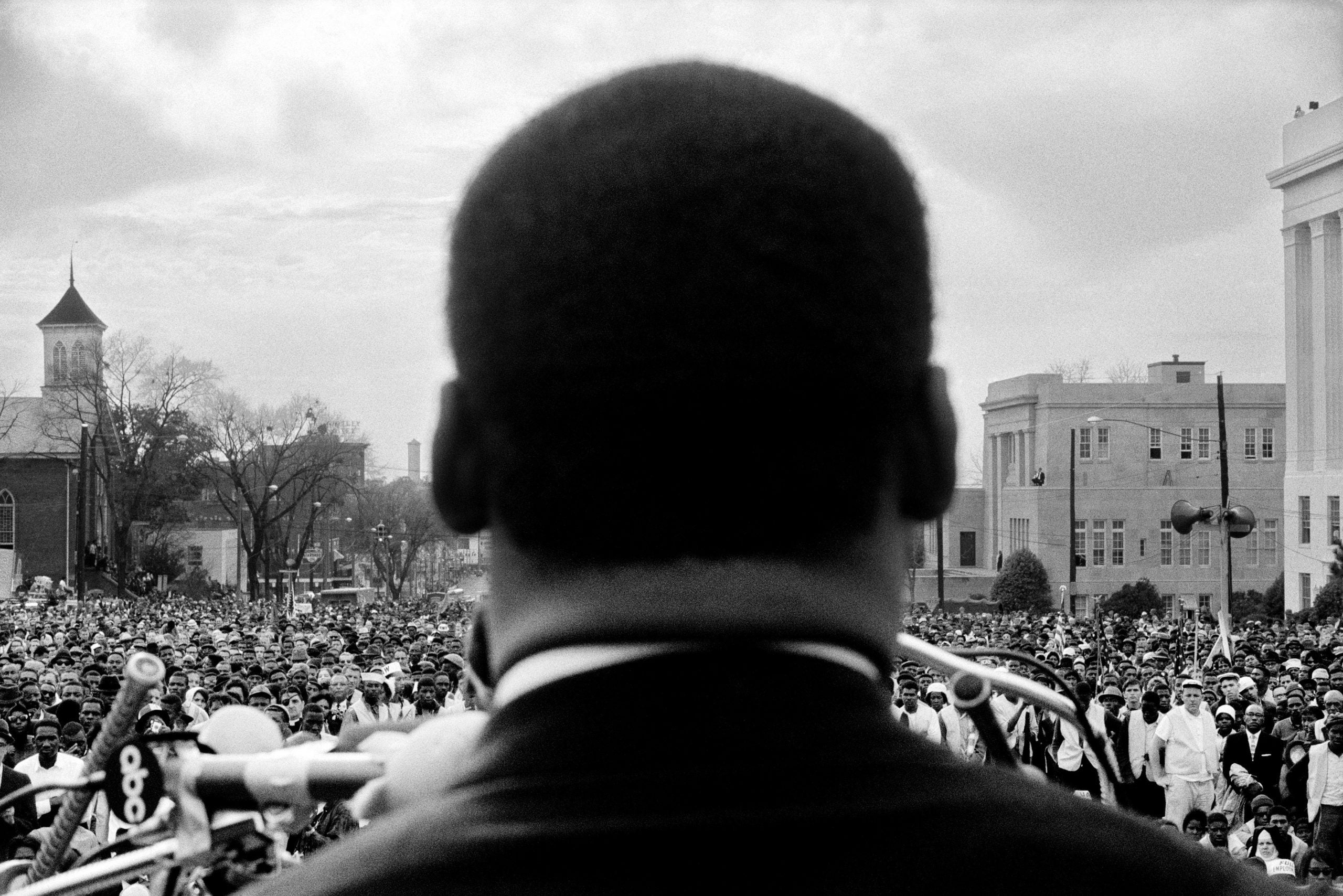

Growing up a Jersey girl I vowed never to subject myself to the overt racism that lives in the bowel of the “new south.” And what that means for a woman with two immigrant parents who learned American history from a school textbook and museum visits, was avoiding two states, in particular. In my eyes, the hatred harvested in Mississippi and Alabama were responsible for the deaths of the four little girls at the 16th Street Baptist Church, the torture of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, and the brutal lynching of Emmett Till. More specifically, Montgomery was the home of the bus boycotts, the first Capital of the Confederacy and the place where segregationist Governor George Wallace famously said, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

Together the two states were home to thousands of racial terror lynchings, and quite frankly, I had no desire to step foot in the part of the country where that history took place. I guess you can say I prefer my racism a little more under the radar. The kind you recognize for what it is, but easily brush off with swear words under the breath. I easily resolved that Alabama was one of those pieces of America I would simply never see.

But two years ago I felt my stance on the Deep South state starting to shift. It was spurred by a press release that came across my desk and detailed the opening of a new kind of museum. The kind that addressed the barbarity of the criminal justice system, confronted the racist history of our country’s “past” and sought to be a teacher of how racial bias runs alongside nearly every governmental structure this nation has ever known. Even more enticing, Montgomery’s Legacy Museum was the brainchild of Bryan Stevenson, a man who had earned renown for preaching equal justice and representing incarcerated individuals on Alabama’s death row.

Now I am my mother’s child, and as I’ve written before, her thirst for cultural awareness harnessed my own. If there was a new museum in Montgomery, Alabama, I for sure wanted to see it. Weeks before the 2020 new year, that opportunity finally came.

Just Mercy, the film based off of Stevenson’s life, was hitting limited theatres with a full rollout weeks later. And I was invited to the place where the story unfolds. I knew from those history books and countless museum visits the significance that Montgomery holds. But what I didn’t know was I’d grow pretty fond of the place I was once adamantly avoiding.

Montgomery, much like Memphis, will likely always be linked to the struggle for equal rights. But what’s happening in both cities is a revitalization that honors its history while working diligently to move past that inherent stronghold. In 2019, the southern city elected its first Black mayor. And in talking to him, it’s obvious that more change is on the way. But even before Steven Reed became its leader, Montgomery was already on its way to redefining its character.

Newly built coffee shops, a Caribbean cafe, and a very impressive tap house are just feet from the months-old statue of the late Rosa Parks. While standing in the center of Court Square, I saw the celebrated icon to my left, the famous Dexter Street Baptist Church to my right, and directly in front of me, the steps where Wallace once gave his regrettable speech. Behind me was the Legacy Museum, fancy restaurants, my recently erected hotel. And where my feet were placed, the ground where enslaved Africans met their fate.

It was interesting to see just how seamlessly the new met the old. How Parks’s former place of business became a popular mixed-use complex. How a one-time auction block became a visual selling point for urban condos. I guess Montgomery, like me — like all of us, really — is in a constant state of evolution, working steadily to establish its next iteration.

In the four days I was there I covered a lot of ground, taking in my dose of historic sites, while thoroughly enjoying the newer staples. A well-planned itinerary gave me a chance to learn more about racial terror lynchings at The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The Rosa Parks Museum was an opportunity to become more familiar with my soror. And I even had an opportunity to tour the Equal Justice Initiative, the very place that spurred the book Just Mercy before it became a theatrical hit.

But I also went off-script a little, relishing in the less-touristy, but equally enjoyable parts of the city that make Montgomery what is. Places like the King’s Canvas, an art studio founded by Kevin King that gives underdeveloped artists a place to explore their craft. Places like Barbara Gail’s, which sits in the center of the community and serves the kind of breakfast one can only dream of. By the time I left Montgomery, I felt like I was among family. I had sat in at a city council meeting, chopped it up over beers with new friends at a microbrewery, stayed up way past my bedtime to enjoy nightcaps with my guides, and asked a million questions about the place I was starting to seriously rethink.

On my last day in the city, I had a special surprise ride pick me up. It was Michelle Browder in a decked out trolly, waiting just outside the Spring Hill Suites. When I boarded she told me to sit on the “Queen’s throne” for my last ride throughout Montgomery, and a few minutes later we pulled up at her she shed. There she mixes the new with the old, historic artifacts with newly-discarded gems. Like an unassuming art gallery with little easter eggs hidden behind its door. And as she gave me the grand tour of the city, I began to establish that I really did like it there.

Before I hopped in the car to head to the airport, Michelle gave me a special gift to remember my time. It was a broken piece of glass from the Holt Street Baptist Church, an important landmark on the US Civil Rights Trail. She instructed me to put a magnetic strip behind it, place it on my fridge and think of my time there when I look at it.

One day soon I’ll get around to it. But for now, it occupies a special place on my bedroom desk. A piece of Black history that I faced with courage. A reminder of what will never be lived again.