Phillis Wheatley was a well-known poet and literary sensation during the 18th century.

Born in May 1753, she was kidnapped from Gambia, West Africa at about the age of 7 and brought to Boston, Massachusetts, where she was then purchased as a domestic servant by the family of John Wheatley, a prominent Boston merchant. Her first name was derived from the ship, “the Phillis,” that brought her to the American colonies.

Over the course of her short life, Wheatley wrote more than 100 poems, many of which focused on biblical themes, political issues and, at times, the cruelty of slavery. She is a pioneer of Black American literature, and centuries later, her work continues to inspire generations of Black poets and writing communities.

In honor of her birthday today (May 8), here are five facts to know about Wheatley’s life and incredible legacy.

Phillis Wheatley was given an unprecedented education.

Wheatley was provided with an education that was virtually unheard-of for women and enslaved Black people living in 18th-century colonial America. The Wheatley family, particularly their daughter Mary, taught her how to read and write. Within 16 months of her arrival to America, she was able to read the Bible and classic Latin, Greek and British literature, and she quickly immersed herself in studying history, geography and astronomy.

Wheatley successfully defended the authenticity of her poems to racist critics.

At about the age of 12, Wheatley began to write poetry. On Dec. 21, 1767, she had her first poem, “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin,” published in Rhode Island’s Newport Mercury newspaper. As she became famous for her work, some white colonists questioned the authenticity of her poems because they couldn’t believe a Black woman had written them.

To counter her critics, Wheatley appeared before a panel of 18 prominent Bostonians to defend her poetry and prove her authorship. The details of that meeting are unknown; however, Wheatley was able to convince the panel that she was in fact the author of her poems, and she subsequently received a letter of support that attested her abilities.

She published her first book of poetry in London and was soon emancipated.

Even after Wheatley defended her work and received a letter of attestation, many colonists were still unwilling to support literature by a Black person. So, in 1773, she sailed to London, where she met a number of influential people, like Benjamin Franklin, who celebrated her work.

With the financial help of Selina Hastings, a wealthy British countess, Wheatley had her first collection of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, published and circulated.

In addition to becoming a published poet, she soon became a free woman. After she left London and returned to Boston, the Wheatley family emancipated her.

Wheatley was the first Black American to have a published poetry book.

With the publication of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral in London, Wheatley became the first Black American person to have a published book of poetry.

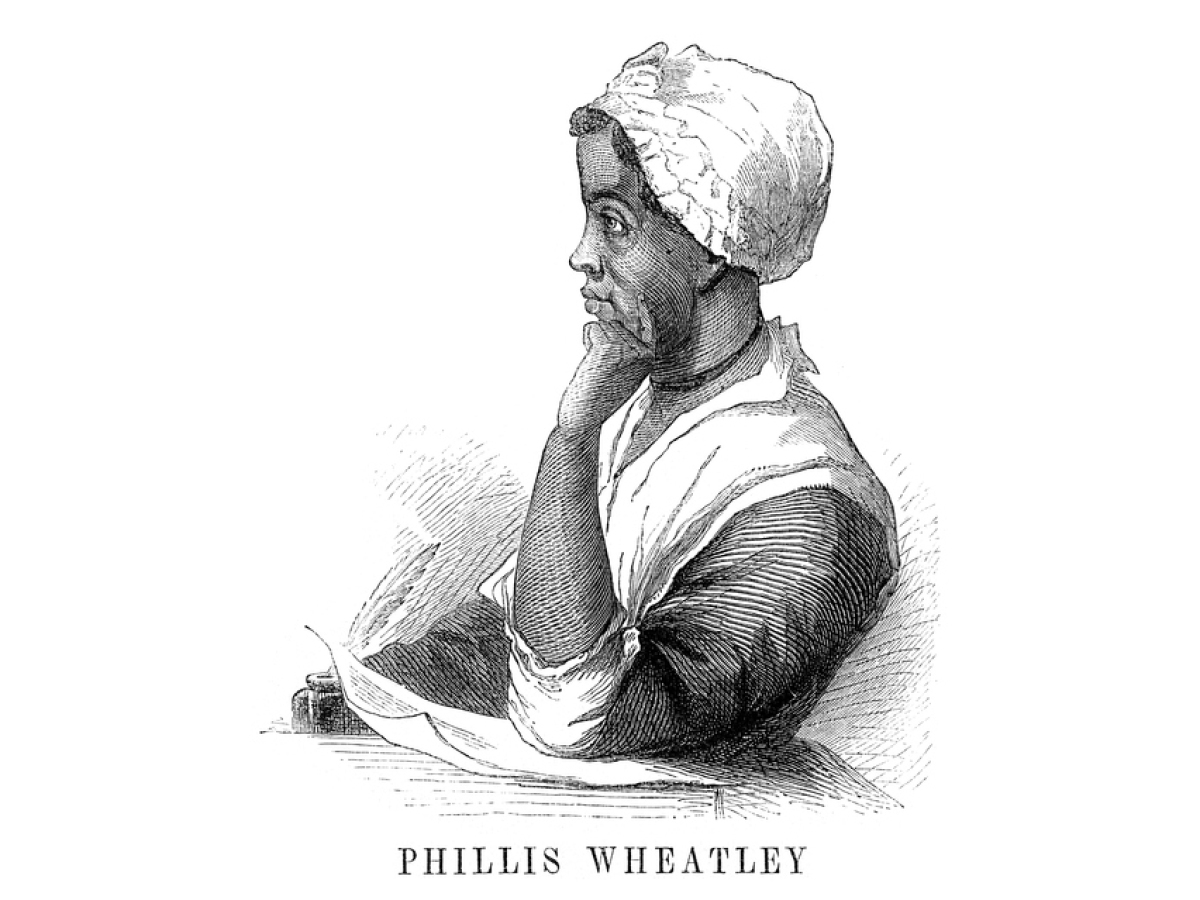

About one-third of Poems on Various Subjects consists of elegies about deceased friends and notable figures. Her poetry book was reviewed in at least eight different London magazines, and it garnered attention throughout England and the American colonies. The book’s cover page features a portrait of Wheatley that was created by enslaved Black artist Scipio Moorhead.

Her work played a role in the 19th-century abolitionist movement.

Poverty and illness led to Wheatley’s death on Dec. 5, 1784. Though she was not alive to see it, by the mid-19th century, abolitionists were beginning to use Wheatley’s poems as a means to challenge white supremacy, and to show that slavery was a restriction to Black brilliance. For example, Boston-based abolitionist newspaper The Liberator published 37 of her poems over a 10-month period in 1832, all in an effort to celebrate Wheatley “as proof positive of black intellectual achievement.”

As the National Women’s History Museum states: “In addition to making an important contribution to American literature, Wheatley’s literary and artistic talents helped show that African Americans were equally capable, creative, intelligent human beings who benefited from an education. In part, this helped the cause of the abolition movement.”