On a Sunday morning in late spring near Seattle’s Magnuson Park, a baby lay in the still-warm blood of his young mother.

She brought a knife to a gunfight, and the gunslingers feared for their lives. Seattle Police Officers Jason Anderson and Steven McNew, both White, reached for their handguns, instead of less-lethal options available on their persons, and within sight and sound of her five children, cut down young Black mother Charleena Lyles. Last month, those officers were dismissed from the wrongful death lawsuit.

Charleena Chavon Lyles, 30, made a call for police assistance, summoning them to her home on a report of burglary. Responding officers Jason Anderson and Steven McNew of the Seattle Police Department, both White, described Lyles as presenting calmly at first, then suddenly brandishing a knife, eventually two.

According to SPD’s Force Investigation Report(FIR), officers warned Lyles to get back, then McNew yelled out “Taser,” to which Anderson replied “I don’t have a Taser.” Seconds later, Anderson and McNew fired seven rounds on her, two through her back.

When Lyles fell to the floor, her 2-year-old son moved toward her from the living room, where he’d seen it all, and climbed onto his mother’s body, near the kitchen where she lay face-down and riddled with bullets.

“He laid in her blood,” says cousin Katrina Johnson during our meeting last month, retracing the catastrophe as she was swallowed up in a wave of horror and heartbreak.

“You see these stories all over the nation, but you don’t think that your family is going to be the story. You don’t think it’s going to happen to your family, and when it does, you have no idea what to do.”

Lyles was a Black woman, a mother of five children ages 12, 11, 4, 1; and one in her womb. She was about 4 months pregnant. The King County Medical Examiner Autopsy Report indicates that a bullet entered Lyles’ body at the right abdomen near her navel and tore through her intestines, perforating her uterus before exiting at her left pelvis. This particular gunshot wound was likely fatal for the unborn child.

After the officers shot Lyles in the presence of her children, McNew instructed another officer to cover their eyes and guide them around their mother as she was expiring on the floor. They wanted the children away from the scene.

Lyles’ oldest child wasn’t at home when it happened. “She found out by Snapchat,” Johnson said, in a message something like ‘the police killed your mom.’ From that day forward, she says, “There’s been division, two different sides of the family, about what should happen with the children. It’s been hell, really.”

Corey Guilmette is the attorney representing Johnson, Monika Williams, Lyles’ older sister; and other members of the family in the eventual inquest into Lyle’s shooting death by SPD.

“Charleena’s death is all the more tragic because she was pregnant at the time, and the decision of officers Anderson and McNew to kill her not only ended her life but robbed her unborn son of the opportunity to live. The killing of Charleena’s son is a striking example of how deep and far-reaching the devastation is when police officers make a decision to kill.”

Seattle Police Officer Training, Certification, Protocols, and Accountability

McNew had been on the job for 11 years. Anderson, only 2. Both officers had received Crisis Intervention Team training (CIT), both were aware of an officer safety caution with regard to Lyles—the result of a prior call for police assistance at her apartment, one in which she had brandished a pair of shears—and both officers should have been aware of her court-ordered mental health monitoring, put in place immediately after that incident.

Lyles had been in counseling for some time before her state-sanctioned death, and had been under monitoring established in a Mental Health Court order just days before. It’s been reported that she had been prescribed medication to support her mental health, but being pregnant, refused it.

Further, Anderson had been certified to carry a Taser, and the City of Seattle Police Manual dictates that officers trained to carry a Taser must do so. Anderson admitted to investigators that he had chosen not to carry his Taser, and said he’d made that decision because its battery had died. The investigation showed that Anderson’s Taser had been sitting in his locker for 10 days with a dead battery, and that he, without permission and against protocol, had worked several shifts without this accompanying de-escalation device. It’s only through a series of verbal and written notifications by protocol and chain of command that an officer trained to carry a Taser may forego carrying a Taser, and carry a less lethal tool such as a baton or pepper spray instead.

Incidentally, Anderson had both of these less lethal tools, a baton and pepper spray, on his person at the time of the encounter, but when faced with this 100-lb Black woman standing 5’3,” he chose to unholster and discharge his Glock instead. Both officers preferred lethal tools on that fatal morning.

“Officer Anderson chose not to carry his Taser, in violation of department regulations,” says Guilmette, “so that his vest and belt would be a little less heavy and he could be a little more comfortable. Charleena would likely be alive today if Officer Anderson had been carrying his Taser.” Guilmette logically concludes that, had Anderson not prioritized his comfort over the safety of the public, two deaths would have been avoided and children would not be orphaned.

The officers’ CIT training and the safety caution, Lyles’ court-ordered “look see” status, and surely the presence of three minor children in the home, all warranted and should have set in motion a specialized police response emphasizing calm and de-escalation—a peace officer response.

In Shock and Trauma, Lyles’ Son Questioned

Anderson told investigators that immediately after the shooting a juvenile stepped out of a bedroom into the hall asking what had happened and that one of the two officers, McNew or himself, told him to return to the bedroom.” Speaking of her nephew, Williams laments, “He’s going to remember that for the rest of his life.”

Considering all that Lyles’ 11-year old son had seen and heard, he must have been in an unimaginable state of fragility and shock, but as his mother was taking her last breaths under straps on a slab in the building’s exterior hallway, he was already being questioned, and in a manner out of sync with child interview protocols established by the King County Prosecutor’s Office.

Within an hour of his mother’s violent death at their hands, multiple officers inquired of him—what happened, whether the gunshots woke him, whether he saw anything, and if he was sure of what he saw. This feels like a deep violation of this child’s sacred space to process. To cry and rage.

Guilmette says, given the trauma of that day, even he has yet to approach the children for discussion.

Wrongful Death Lawsuit

A wrongful death lawsuit was brought by the Lyles Estate, Charles Lyles who is Charleena’s father, and other members of the family—excluding Johnson and Williams—against the City of Seattle, officers Anderson and McNew, and Solid Ground, the management company for the housing complex where Charleena lived with her children.

Lyles had initiated tens of calls for police assistance over a period of about a year and a half leading up to her death, many times for domestic violence at the hands of her long-term, sometimes boyfriend—the father of her oldest kids.

“Lena had asked to move for domestic violence reasons,” Johnson says, “and nothing was ever done about it.” Johnson feels that Solid Ground has culpability in what happened to her cousin, but the Court disagreed and allowed Solid Ground’s motion for dismissal from the case last April.

In an opinion shared in Seattle City Insights — “Despite proclaiming their legal innocence, Solid Ground published a list of reform measures they have taken since the incident last June.”

Chief of Police Carmen Best, a Black woman whose been with SPD for 27 years, placed Officer Anderson on a two-day suspension in disregard for the tragedy that followed his decision, and in another blow to the Estate last month, both officers were dismissed from the wrongful death case, with prejudice.

Washington State Child Protective Services

The SPD Force Review Board had determined in November 2017 that the officers’ actions and decision were consistent with policy and training, so neither Johnson nor Williams were surprised at this latest dismissal.

“People are probably thinking, ‘the family just wants money.’ Not so, she says. To her, it’s just blood money, and “most of Lena’s Seattle-based family, we weren’t for a lawsuit.”

But with Guimlette’s help, Johnson, Williams and other family members will be one of the first families to benefit from King County’s recently revamped inquest process—one designed through community input for better family representation in cases of officer-involved deaths.

“Charleena’s inquest will be the first time that her family members get to have their voices heard,” says Guilmette. “Until now, the Seattle Police Department has largely controlled the narrative. Charleena’s family members anticipate that a different story will emerge with this opportunity to finally critically examine the events surrounding her death.”

“Everybody’s interests in this is a little different,” Johnson says, but what she wants is simple—“Someone to take care and love those babies, and not because they see a payday in their future.” Williams agrees. “That’s been my main thing, the kids, and them being somewhere with somebody that can take care of all their needs.” And neither of them trusts Washington State Child Protective Services.

“If the murder of my cousin wasn’t enough,” Johnson says, “what CPS is doing is absolutely atrocious and quite frankly if I was looking to sue anybody, it would be CPS.”

Recalling the systemic obstructions to her advocacy for the children, and an inability to work in partnership with the agency, Johnson says, “they’ve said things like ‘Our family will never get the kids’ and ‘We’re nothing more than caregivers’. We’ve had to call Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. I think there needs to be a light shined on that aspect.”

In an unusual move, one of Lyles’s four minor children was appointed by the Court to be Guardian ad Litem, and in that capacity, the child decided that she and her siblings would reside with her paternal grandmother, in a town about an hour outside of Seattle. “The grandmother has been around. She knows all of the children,” Johnson says, but for her, this is an uncomfortable outcome because “She’s not kin to all of the children. [CPS] cares nothing about kinship, about family trying to get the kids and provide stability.”

Johnson is long past anger, but she’s in a place of unrest, and she hasn’t been able to really grieve. There’s been so much change with status of the children and where they’ll live, and “it just keeps ripping that Band-Aid.” She needs answers—“Is this their final place, or is this just their next place?”

How She’s Remembered

Video captured over a 24-hour period leading up to Lyles’s last call to SPD showed no activity to confirm that burglary had occurred. Johnson doesn’t know why Lyles would have pulled knives during the encounter with police, but she believes that her cousin’s mental illness was a contributing factor.

Investigations continued in the months that followed. Contractors for Solid Ground conducted testing for methamphetamine in Lyles’ apartment. Results showed a significant presence of the drug.

According to the FIR, a couple of months after Lyles’s death, an employee of Solid Ground contacted SPD with concerns that the organization had been “covering up information that could have prevented the shooting.”

Charleena Lyles was like so many of us—a Black woman and a single mother in this well-constructed socio-economic stronghold called America.

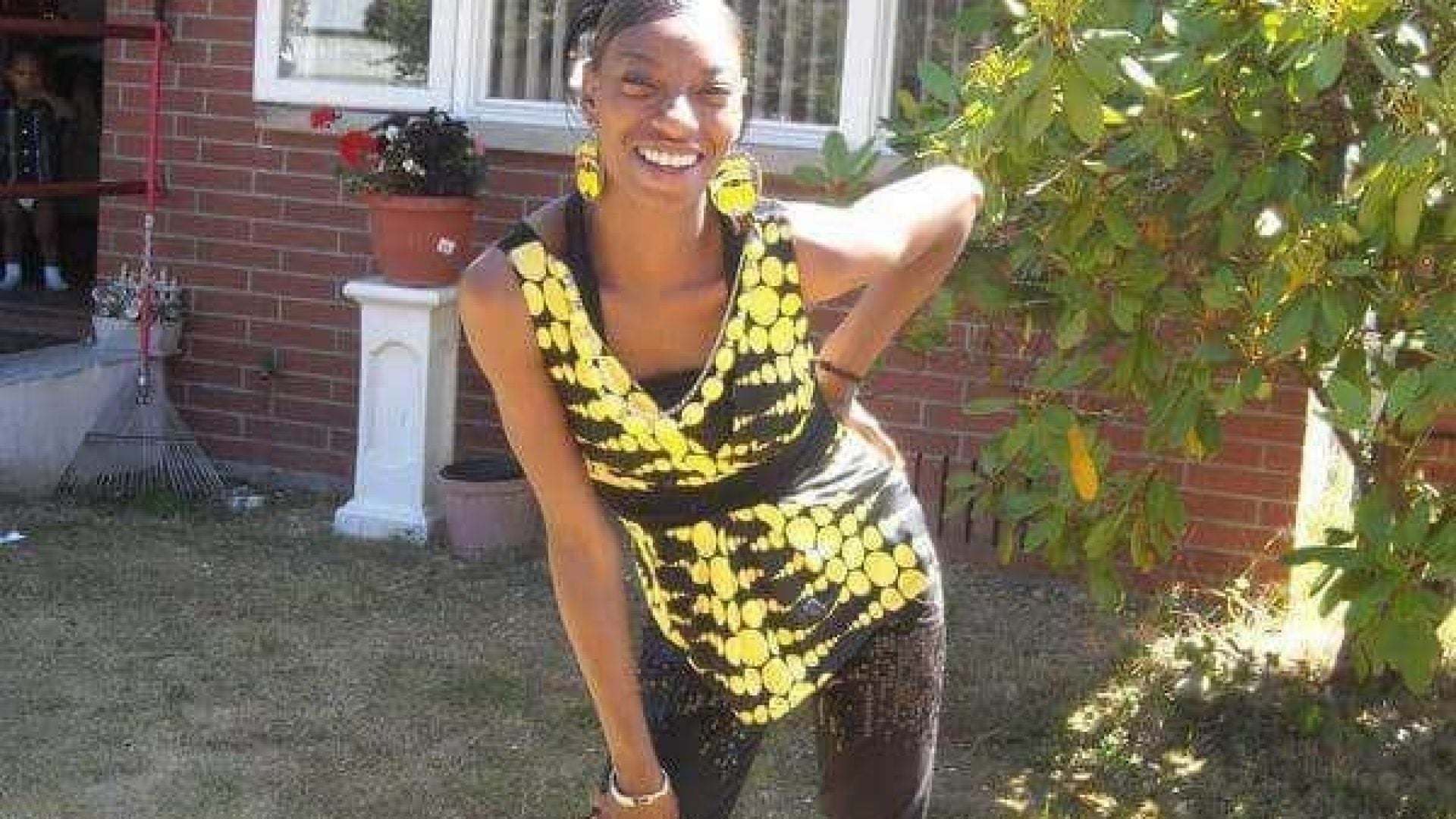

In spite of it all, she’s remembered for her smile, and “whenever you saw her, you saw her kids,” Johnson says. She loved long bus rides with the kids, taking them to the library and the park. Seattle Public Library cards and a bus transfer were recovered from a pocket of the jacket she was wearing when she was killed—bittersweet souvenirs.

Systems that dehumanize Black and Brown people are the very brick and mortar of social conditions that support our extermination, with justification and impunity.

Black Family, let’s fight for our side to be counted as human and equally valued. Let’s tend the gardens of our consciousness, stop telling ourselves “it’s not my business.” Let’s do the work that’s desperately needed and well within our reach. Let’s grow towards those self-sacrifices that could save our sisters and brothers.

Because we are Aura Rosser, Natasha McKenna, Korryn Gaines, and Charleena Lyles; and because all we have is one another. Let our hearts swell in righteous anger, and say their names.

Carla Bell is a Seattle-based freelance writer focused on civil and human rights, social impacts, abolition, culture, and arts. Carla’s work has appeared in Ebony magazine, and a number of other print and digital media publications.