This article originally appeared on Time.

(WASHINGTON) — The implosion of the Senate Republican health care bill leaves a divided GOP with its flagship legislative priority in tatters and confronts a wounded President Donald Trump and congressional leaders with dicey decisions about addressing their perhaps unattainable seven-year-old promise of repealing President Barack Obama’s law.

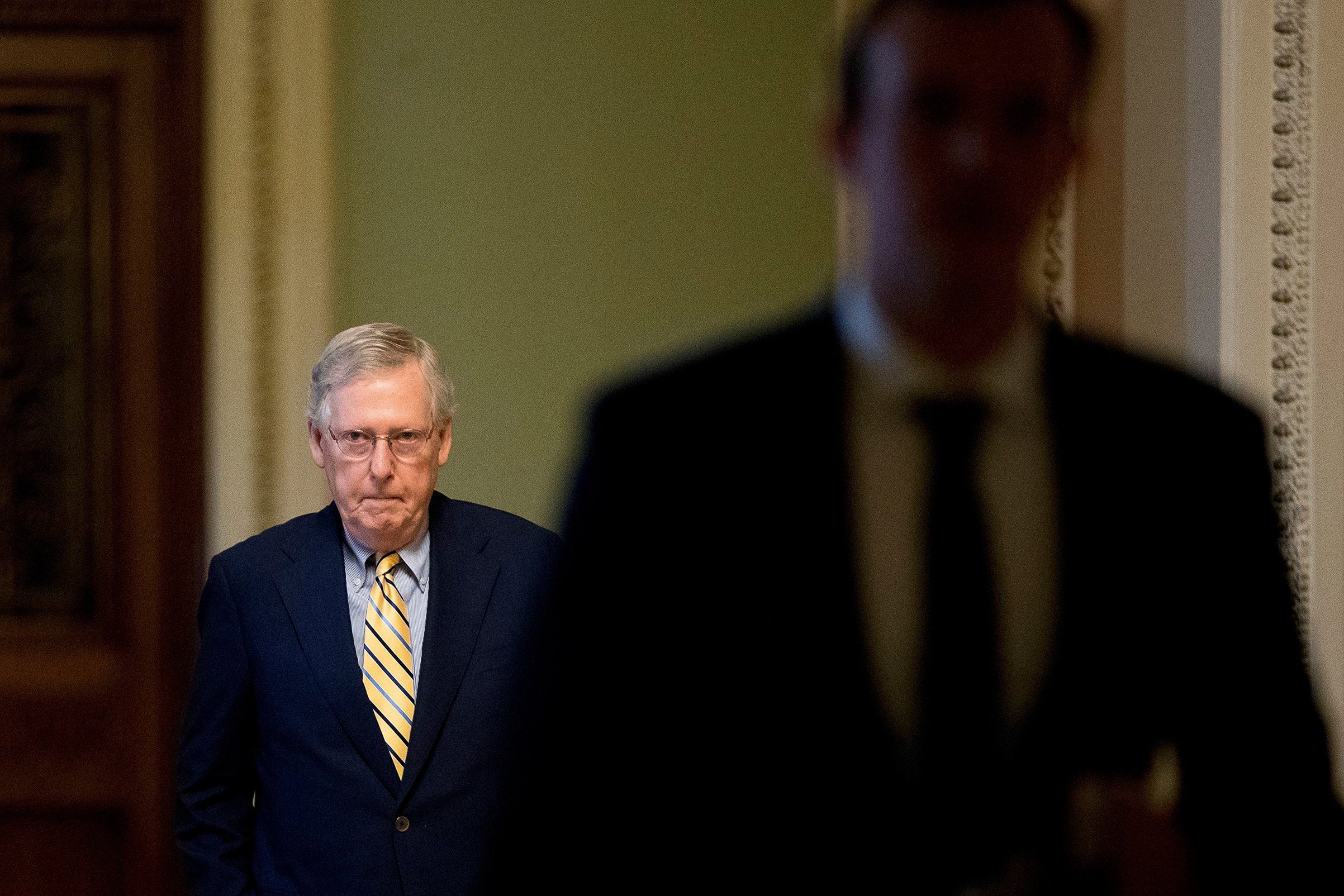

Two GOP senators — Utah’s Mike Lee and Jerry Moran of Kansas — sealed the measure’s doom late Monday when each announced they would vote “no” in an initial, critical vote that had been expected as soon as next week. Their startling, tandem announcement meant that at least four of the 52 GOP senators were ready to block the measure — two more than Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., had to spare in the face of a wall of Democratic opposition.

“Regretfully, it is now apparent that the effort to repeal and immediately replace the failure of Obamacare will not be successful,” McConnell said in a late evening statement that essentially waved a white flag.

It was the second stinging setback on the issue in three weeks for McConnell, whose reputation as a legislative mastermind has been marred as he’s failed to unite his chamber’s Republicans behind a health overhaul package that’s highlighted jagged divides between conservatives and moderates. In late June, he abandoned an initial package after he lacked enough GOP support to pass.

The episode has also been jarring for Trump, whose intermittent lobbying and nebulous, often contradictory descriptions of what he’s wanted have shown he has limited clout with senators. That despite a determination by Trump, McConnell and House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., to demonstrate that a GOP running the White House and Congress can govern effectively.

Now, McConnell said, the Senate would vote on a measure the GOP-run Congress approved in 2015, only to be vetoed by Obama — a bill repealing much of Obama’s statute, with a two-year delay designed to give lawmakers time to enact a replacement. Trump embraced that idea last month after an initial version of McConnell’s bill collapsed due under Republican divisions, and did so again late Monday.

“Republicans should just REPEAL failing ObamaCare now & work on a new Healthcare Plan that will start from a clean slate. Dems will join in!” Trump tweeted.

But the prospects for approving a clean repeal bill followed by work on replacement legislation, even with Trump ready to sign it, seemed shaky. Trump and party leaders had started this year embracing that strategy, only to abandon it when it seemed incapable of passing Congress, with many Republicans worried it would cause insurance market and political chaos because of uncertainty that they would approve substitute legislation.

McConnell’s failed bill would have left 22 million uninsured by 2026, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, a number that many Republicans found unpalatable. But the vetoed 2015 measure would be even worse, the budget office said last January, producing 32 million additional uninsured people by 2026 — figures that seemed likely to drive a stake into that bill’s prospects for passing Congress.

That would seem to leave McConnell with an option he described last month — negotiating with Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. That would likely be on a narrower package aimed more at keeping insurers in difficult marketplaces they’re either abandoning or imposing rapidly growing premiums.

“The core of this bill is unworkable,” Schumer said in a statement. He said Republicans “should start from scratch and work with Democrats on a bill that lowers premiums, provides long-term stability to the markets and improves our health care system.”

Similar to legislation the House approved in May after its own setbacks, McConnell’s bill would repeal Obama’s tax penalties on people who don’t buy coverage and cut the Medicaid program for the poor, elderly and nursing home residents. It rolled back many of the statute’s requirements for the policies insurers can sell and eliminated many tax increases that raised money for Obama’s expansion to 20 million more people, though it retained the law’s tax boosts on high earners.

Besides Lee and Moran, two other GOP senators had previously declared their opposition to McConnell’s bill: moderate Maine Sen. Susan Collins and conservative Rand Paul of Kentucky. And other moderates were wavering and could have been difficult for McConnell and Trump to win over because of the bill’s Medicaid cuts: Alaska’s Lisa Murkowski, Cory Gardner of Colorado, Rob Portman of Ohio, Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia and Dean Heller of Nevada, probably the most endangered Senate Republican in next year’s elections.

The range of objections lodged by the dissident senators underscored the warring viewpoints within his own party that McConnell had to try patching over. Lee complained that the GOP bill didn’t go far enough in rolling back Obama’s robust coverage requirements, while moderates like Collins berated its Medicaid cuts and the millions it would leave without insurance.

McConnell’s revised version aimed to satisfy both camps, by incorporating language by Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas allowing insurers to sell skimpy plans alongside more robust ones, and by adding tens of billions of dollars to treat opioid addiction and to defray consumer costs. His efforts did not achieve the intended result.