This article was originally published January 21, 2019

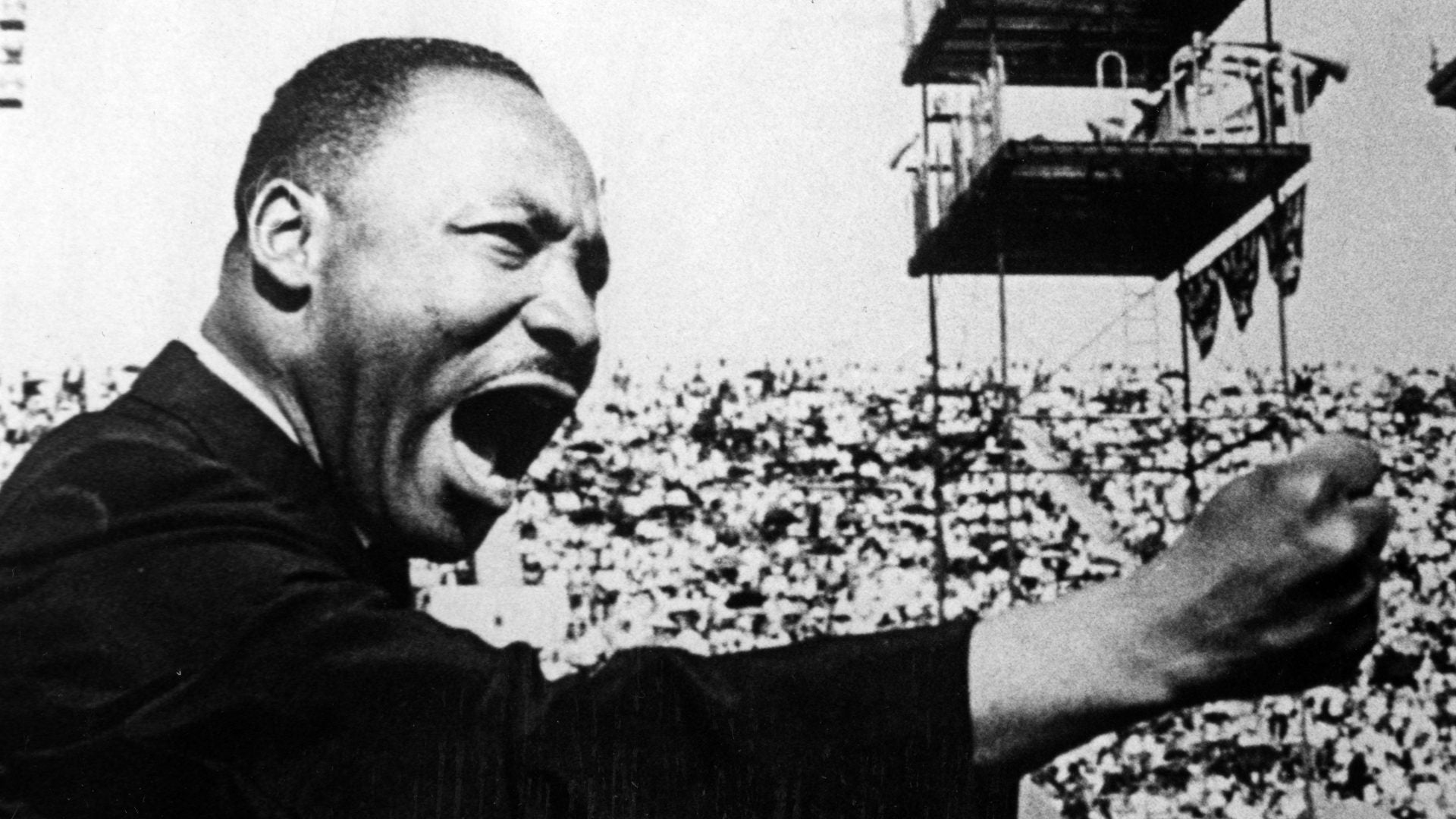

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would have celebrated his 90th birthday this year, a long life deserved by a man who spent most of his days fighting for justice, equality and liberation and acting as a moral bridge between people. But for his service and dedication to people around the world, King wouldn’t be rewarded with a long, joyful life. Instead, the Nobel laureate was assassinated at the age of 39, leaving behind a wife, four children and a community trying to figure out how to move forward in an era when so many leaders were ripped away from it.

For many, moving forward wasn’t just a matter of embodying King’s moral resolve and ethical fortitude—it was also a matter of controlling the narrative about his legacy. King was a revolutionary and a staunch freedom fighter, a man who gave his life not only addressing but also attacking racism, militarism and poverty. A man who once said, “True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice.”

But this isn’t the King who is widely celebrated, revered in the mainstream public and quoted on holiday cards. This King is someone created to be weaponized and leveraged against “radical” ideals and racial tensions and to keep movements at bay.

In an era with leaders such as Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis and Malcolm X, King’s voice and message were often seen as less divisive by comparison. Because of that, the media, politicians, educators and other stakeholders have strategically reimagined who King was and re-engineered the way many view him.

An example of this can be seen in King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, in which he pointedly spoke about the United States and its failure to respect and support Black Americans. “Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’ But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt,” he said.

Instead, the focus has been on the more widely palatable parts of that speech, such as, “I have a dream that one day right there in Alabama, little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” This statement is often taken out of context and used to defend a neoliberal and faux-progressive idea of a post-racial society, or a need for “just getting along,” while not addressing that the United States, in fact, has not changed and may be regressing.

King is the same man who was monitored and demonized by his government and made out to be anti-American because of his outspokenness against the Vietnam War and the state of the country’s moral and ethical values.

“We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism are incapable of being conquered,” King said in his “Beyond Vietnam” speech.

He was found to be so divisive that people like the late John McCain felt that he didn’t deserve to be celebrated with a national holiday in 1983, but years later openly aligned themselves with his reimagined values.

King’s legacy has purposely been distorted to conflate his position of nonviolence with being docile and to misrepresent his grace as passiveness—so much so that even Donald Trump has described King as “a man who I’ve studied and watched and admired for my entire life.” He made this quote at the opening of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, amid a boycott of his attendance that was led by notable civil rights leaders such as Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, who worked with King and was a friend of his. “President Trump’s attendance and his hurtful policies are an insult to the people portrayed in this civil rights museum,” he said in a joint statement with Rep. Bennie Thompson of Mississippi.

Yet Trump still found it on brand and on message to reference King as a “hero” of his, despite the profound differences in their morals, ethics and beliefs.

We are in an era of heightened global racism, while white nationalists are occupying the highest offices in America and actively working to undermine all of the work done to liberate our communities. Because of this, it’s more important than ever that we embrace the fact that King was radical and anti-establishment regarding the oppression of people around the world.

For current and future leaders to be empowered during a time of blatant hatred, King must not be seen as a symbol of centrism or the Black moderate—his life and work must be a tool and resource for radical work and change. We need to be given our king back.