On Tuesday on what would have been Emmett Till’s 82nd birthday, President Biden signed a proclamation which officially names the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument.

Vice President Kamala Harris and members of the Till family were in attendance at the White House ceremony where the news was announced. President “Biden invoked Republican efforts to ban books and ‘bury history.’…‘Darkness and denial can hide much,’ Mr. Biden said. But ‘they erase nothing. We can’t just choose to learn what we want to know.’”

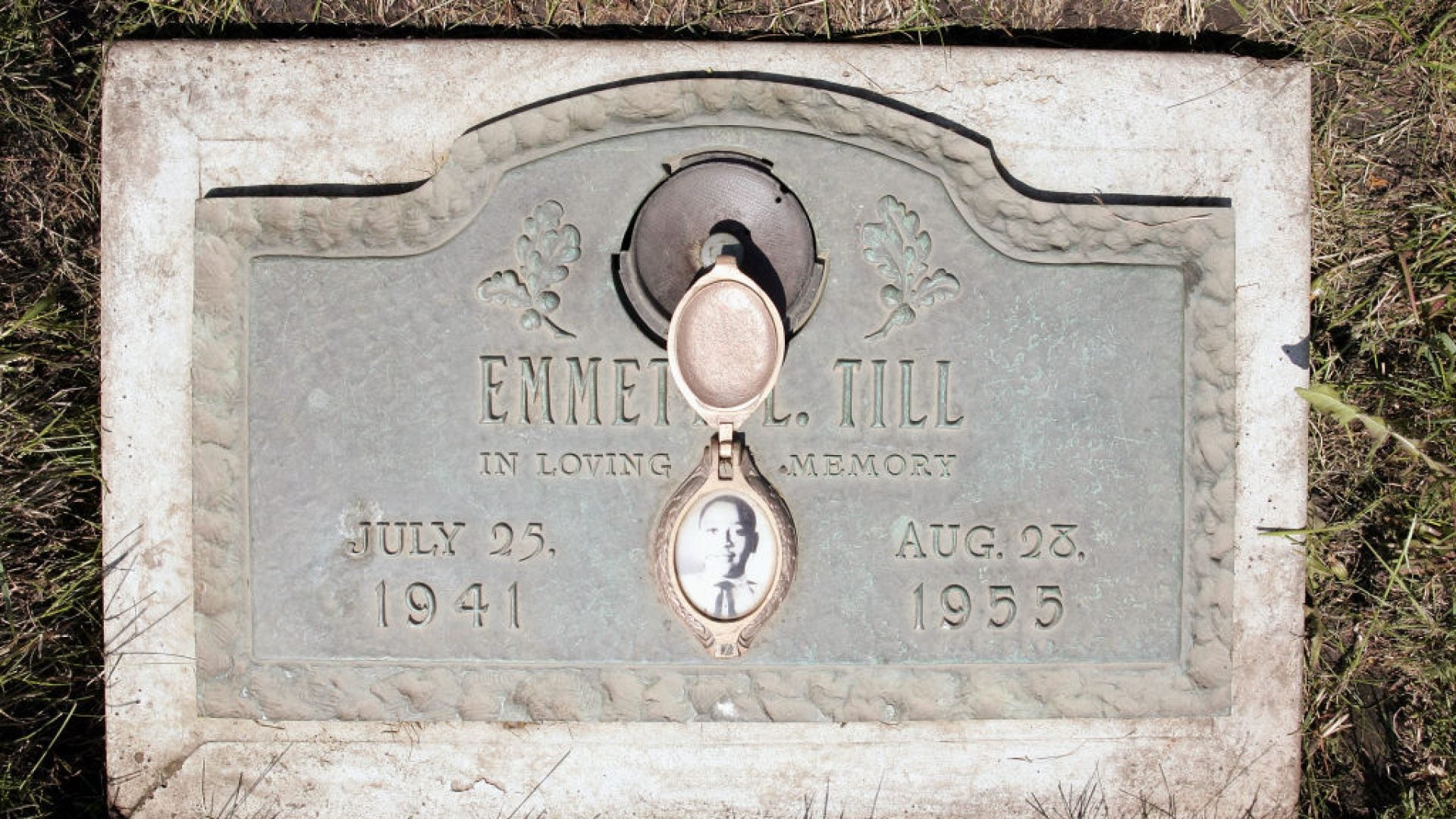

Till’s death, his mother’s decision to hold an open casket at his funeral and her activism thereafter helped galvanize and push the civil rights movement forward. Till, a Black teen from Chicago was visiting family down south in Mississippi during the summer of 1955. “[A]fter he was accused of whistling at a white woman” the 14-year-old was “abducted, tortured and” lynched. His assailants were acquitted of all wrongdoing.

Years after the acquittal, Till’s murderers Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam “confessed to the killing in a magazine.” Even more atrocious, “[f]ifty years after the crime, the shopkeeper’s wife, Carolyn Bryant Donham, also admitted to lying about Till touching her.”

The monument will consist of three places central to Till’s life and his mother’s valiant crusade for justice. “One site is the church where Emmett’s funeral was held, Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, in a historically Black neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side known as Bronzeville.” Till-Mobley’s brave decision to show her son’s mutilated body to the “estimated 250,000 mourners…[who] came to witness the horror for themselves” will always be remembered.

A second “site is the Tallahatchie County Second District Courthouse in Sumner, Miss., where an all-white jury acquitted Emmett’s killers.” Years later in 2007, Till’s family came back to visit the courthouse where town leaders delivered an apology. Simeon Wright, Till’s cousin who was present the night of the kidnapping, was appreciative of the belated efforts of restitution, and said “You are doing what you could. If you could do more, you would.”

The third site “is Graball Landing in Tallahatchie County, Miss., where Emmett’s body is believed to have been pulled from the Tallahatchie River.” A memorial sign had previously been installed near this location in 2008, dedicated in Till’s honor, “[b]ut over the years, the sign was routinely stolen, vandalized or shot at and forced to be replaced. A fourth edition now stands at the site – this time bulletproof and details the history of vandalism.”

When Patrick Weems, executive director of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, learned about the monument, he was brought to tears. Weems said, “I’m so happy for the Till family and also our community that has worked tirelessly to get these sites recognized…It’s just a lot of emotion.” “If we are to grow as a society…we have to process past pain, past wounds that have taken place in this country, and Emmett Till represents some of those wounds,” stated Weems. “I think this allows us to say never again, that this is not who we are anymore,” Weems continued, adding, “This is not who we want to be.”