When Ugandan LGBT activist Clare Byarugaba woke up and turned on her phone on February 28, 2014, she was greeted by the same ominous message over and over: “Have you seen the newspaper?”

A few days before, the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, had signed into law a bill that punished certain sexual acts between two people of the same gender with life in prison and threatened incarceration for those who provided services and support to the LGBT community. In response, a popular tabloid newspaper ran Byarugaba’s name and photo on its front page that day with the headline “Top Ugandan Gays Speak Out: How We Became Homos.”

“All I could think of was, Oh, my God, my mom!” recalls Byarugaba, whose voice catches as she describes her mother’s response: She threatened to hand her daughter over to the police.

Byarugaba left town, fearing for her life after receiving death threats on her phone and via social media. She had seen what happened to out gays and lesbians in her country. In 2011 Uganda’s most visible LGBT activist, David Kato, was bludgeoned to death with a hammer shortly after another tabloid splashed his photo on its front page under a banner that read, “Hang Them.” As the co-coordinator of the Civil Society Coalition on Human Rights and Constitutional Law, an LGBT advocacy group, Byarugaba worried that something similar might happen to her. Speaking out and organizing against her government’s anti-LGBT rhetoric had made her vulnerable.

LGBT PAC Names Aisha Moodie-Mills as First Black Female President

“If you’re in front of a major tabloid, that means you’re a target,” says Byarugaba, 28, who was raised in a small town in southwestern Uganda and now lives in Kampala, the capital and largest city. “But it was also the effect on my family and the kind of shame that I knew it brought them in a country like Uganda that really disturbed me so much. I sent my whole family a message to say I was sorry, and then I went underground.” After several days of hiding out in a quiet town on Lake Victoria under an assumed name without phone or Internet, she reemerged, stronger and more determined than ever.

Byarugaba is part of a new breed of proud and out African LGBT activists who are refusing to be silent in countries where being gay isn’t just dangerous, it’s deadly. LGBT marriage equality has gained strength in Western countries, where it is legal in 22 nations, including Brazil and, most recently, Mexico. In the U.S., 37 states plus the District of Columbia allow same-sex couples to marry. But as more and more people worldwide are embracing their LGBT brothers and sisters, a number of nations in Africa have hardened their anti-LGBT stances.

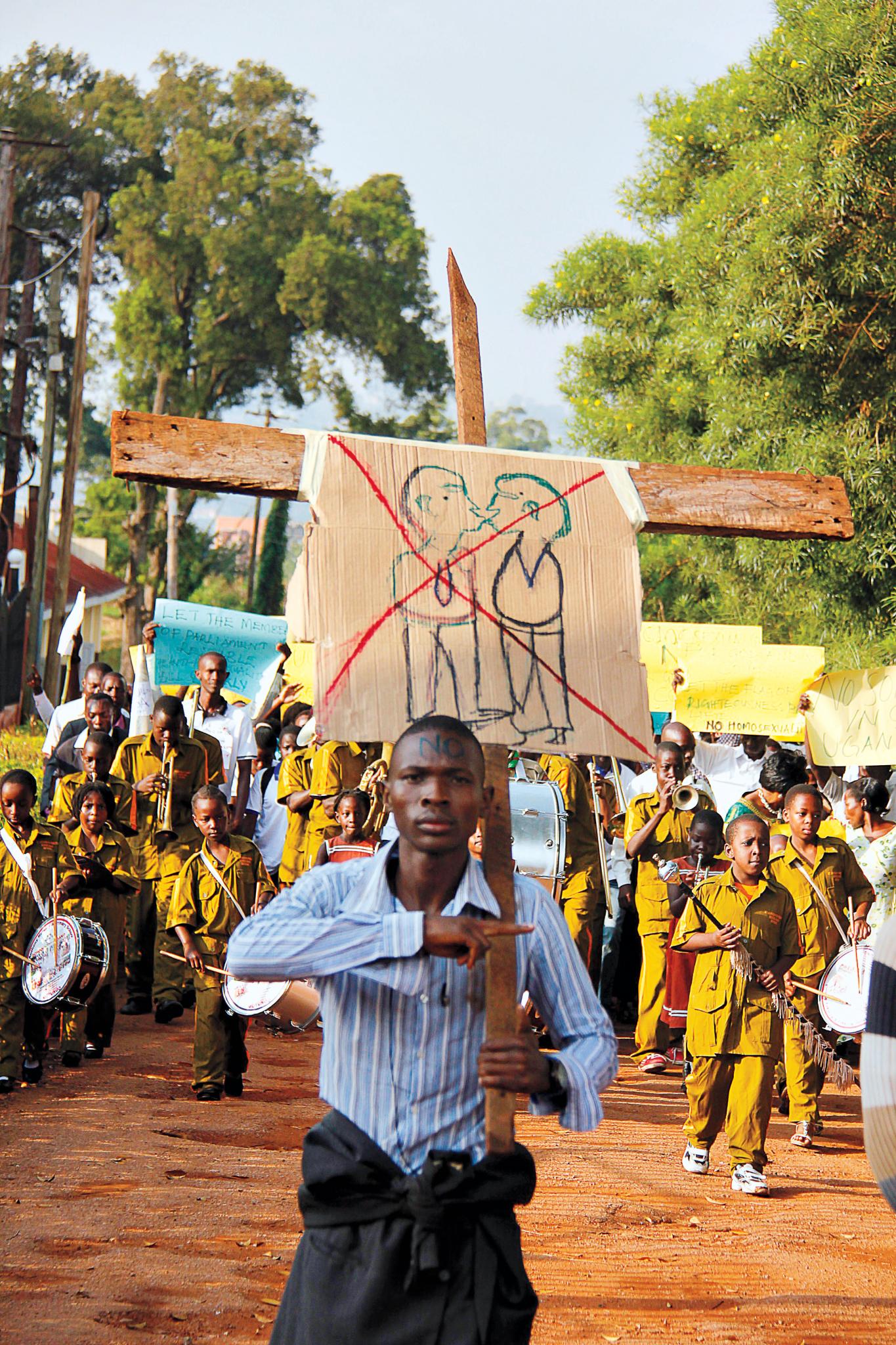

ANTI-LGBT SENTIMENT

While some African countries, like South Africa, have seen pro-gay progress, same-sex sexual activity is illegal in 34 African nations, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Two countries on the continent, Mauritania and Sudan, and parts of Nigeria and Somalia, punish homosexuality with the death penalty. And all across the Motherland, citizens remain stubbornly intolerant of same-sex relationships. In Nigeria, 98 percent of the population believes homosexuality should not be accepted by society, according to the Pew Research Center. Intolerance is nearly as high in Senegal, Ghana, Uganda and Kenya. Even in South Africa, where antigay discrimination has been outlawed and same-sex marriage is legal, 61 percent of residents disapprove of same-sex relationships.

Widespread condemnation from Western countries, including the U.S., has seemingly emboldened some African leaders. In May, Yahya Jammeh, president of The Gambia, threatened gay men living in his West African nation. “If you do it [in The Gambia], I will slit your throat,” he said during a public speech. “If you are a man and want to marry another man in this country and we catch you, no one will ever set eyes on you again, and no White person can do anything about it.”

In the wake of laws and inflammatory speech, LGBT men and women have lost jobs, and homes and have been whipped, stoned, beaten, raped and, like David Kato, murdered. Activists in Nigeria have reported a wave of antigay violence since last year, when that country instituted what is known as a “jail the gays” law, one of the world’s most restrictive anti-LGBT rulings. It criminalizes public displays of affection between same-sex couples and jails groups and individuals who support LGBT rights.

Given the legal jurisdiction, Nigerian authorities often instigate violent crack-downs. Last October, police raided Ifeanyi Kelly Orazulike’s thirty-fourth birthday party at the office of the International Center for Advocacy on the Rights to Health, the HIV/LGBT research and advocacy organization he runs in Abuja, the nation’s capital. The police, brandishing guns, barged in, wrecked the office and rounded up Orazulike and his guests. Orazulike believes his neighbors tipped off law enforcement.

The outspoken activist fought back with a lawsuit against the police, which remains tied up in court. He continues to advocate for LGBT rights and health, but with some trepidation. “I was traumatized, degraded and humiliated,” says Orazulike, who notes that his office was raided by armed officers again three months later, and that time some people were wounded. “We live in fear here. It is understood that if the police can do these kinds of things to you, it gives everyone else free rein.”

Still, Orazulike has dug in his heels and vowed to stay in Nigeria and fight. “Several times I have thought about leaving because I feel so tired, confused, depressed and frustrated,” says Orazulike, the father of two children. “But there is so much to be done here. When I want to walk away, I think about the future and have hope.”

ESCAPING INTOLERANCE

It’s hard to say how many, but growing numbers of African LGBT people have fled their homeland, seeking asylum in safe havens in other parts of the world. The United Nations estimates that more than 40 countries now recognize LGBT persecution as a valid reason for accepting refugees. “There is something of an exodus going on among LGBT Africans who are finding it too difficult to survive in their countries and are heading for the exit door,” explains Charles Radcliffe, who heads the global issues section at the U.N. human rights office in New York City. “Our goal is to have them stay in their countries and help make their lives better. But there has to be a last resort when people’s lives are at risk and they need a safe passage.”

Micheal Ighodaro aches for Nigeria, where he says his heart is. But for now, the LGBT asylum seeker lives in an apartment in the Bronx. An HIV/AIDS educator, Ighodaro attended the International HIV/AIDS conference in Washington, D.C., in 2012, and a story about the event that referenced him as a gay man appeared online. When he returned home to Abuja, his apartment had been set on fire. A few days later, several men attacked him and he suffered broken ribs and a shattered hand. “I was almost killed that night,” says Ighodaro, 29, who works as a program and policy assistant for AVAC (formerly known as AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition), an HIV prevention organization in Harlem. “Then I started receiving very scary, serious threats. Even my own family threatened to have me killed.”

Longtime Ugandan activist and transgender man Victor Mukasa left his country for the United States in 2012 after repeated death threats to himself, his family and friends. “They told me, “We will rape your children in your presence and then kill them,”” says Mukasa, 40, a father of two. “That was when I made the decision to leave.”

Originally known as Juliet, Mukasa describes his early years in Uganda as “hell itself.” After he came out as a lesbian at a young age, his family threw him out. Over the years, he has been insulted, fired and beaten. In the early 2000’s, after hearing about a young Ugandan lesbian who killed herself after she was humiliated for writing a love letter to another girl, Mukasa followed his passion to become an LGBT activist. “I said enough is enough and went on radio and TV and was quoted in newspapers and magazines,” he says. “I began to speak out openly against the injustices and advocated for an end to them.”

Acknowledging that he had always felt more male than female, he began calling himself Victor in 2004. The following year, government officials raided his home, illegally searching and confiscating documents. Enraged, he sued the Ugandan attorney general for police harassment and won. After the lawsuit, however, Mukasa’s life became unbearable. “It went to a different level,” he says. “Now my direct enemy and threat was the state.”

Obama Becomes First Sitting President to Cover an LGBT Magazine

After years of hiding in fear, he finally left Uganda and now runs the Kuchu Diaspora Alliance, a Baltimore-based nonprofit that works with African LGBT refugees and asylum seekers worldwide. The organization strives to address the health, safety and housing needs of the hundreds of displaced Ugandan LGBT citizens, many of whom have fled to nearby Kenya and live in camps, waiting for resettlement. They face unique risks, compared with other refugees, including violence. “Many don’t have the same kinds of support as other refugees because they have been rejected by their families and communities,” says Radcliffe of the U.N. “They really are alone in the world. Asylum is an absolute last option.”

Even those who land in the States say life can feel difficult and lonely. “I left everything, including my family, behind,” says Mukasa. “I love my country. I didn’t want to leave the land where my parents are buried. I would prefer to be home working on our struggles within the movement I helped build.”

SIGNS OF HOPE

A group called The Fellowship Global, spearheaded by an African-American minister from Oakland, is striking back to combat negative rhetoric about LGBT men and women in Africa. Some of the strongest anti-LGBT feelings on the continent have been spurred by conservative evangelical Christians, mainly White, who visit African countries and have been known to stir up anti-LGBT feelings. “People of African descent are a spiritual people, and they respond to messages about God,” says Bishop Yvette Flunder, the organization’s founder. “But much of what folks are hearing about LGBT people comes from White conservatives. One way Africa was colonized the first time was in the name of Jesus.”

Flunder and other Black ministers have traveled to Uganda, Rwanda, Côte d’lvoire, Kenya and other countries to meet with clergy, government officials and organizations. Their goal: to encourage a social justice movement in Africa that includes the LGBT community and to minister to gay and lesbian individuals on the ground, many of whom are deeply spiritual and confused by the hate speech from Christian clergy who visit from the U.S. In response to an appeal from Kenyan gays and lesbians, Bishop Flunder and the executive director of The Fellowship Global, Bishop Joseph Tolton, helped establish the Cosmopolitan Affirming Church for LGBT worshippers in Nairobi last year. “It’s incredibly important that someone says, “I’m Black like you, I am Christian like you and I have a theology to share with you that fully affirms who you are,”” says Flunder, a same-gender-loving woman and senior pastor of the City of Refuge United Church of Christ in Oakland. “That’s a breath of fresh air.”

Flunder and Tolton hope to press the Congressional Black Caucus to hold a hearing on the exportation of homophobia to Africa by conservative Christians. They stress the importance of connecting LGBT rights to the larger struggle for social justice and human rights. Tolton urges churches and community organizations to remember that “Black LGBT lives matter, too.”

Experts believe that we must approach the problems of Africa with care and caution, since even well-meaning support can seem like the brand of Western imperialism that has contributed to strife and chaos throughout the continent. Still, progressive African-Americans have a major role to play. “By learning about this issue and sharing information, African-Americans stand in solidarity with those abroad,” says Radcliffe. “Showing LGBT people in Africa that you care about their struggles can make an important difference.” Adds Orazulike of Nigeria: “Having your support means a lot.”

Understanding that Africans have deep-rooted cultural and familial connections, Clare Byarugaba is creating a Kampala chapter of PFLAG, (formerly known as Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays), a global organization that supports relatives and allies of LGBT persons. She hopes it will encourage people like her own mother to open their hearts and minds to LGBT Ugandans. “I’m passionate about convening mothers to share the kinds of stories about their LGBT children that few people hear in our country,” she says. “I feel like if there’s that alternative family voice then people won’t look at you as an LGBT person; they’ll see you as someone’s child.”

To get involved, learn more and donate to LGBT rights organizations in Africa, visit kuchudiasporaalliance.org, youcaring.com (search “Clare Byarugaba”) and thefellowshipglobal.org.